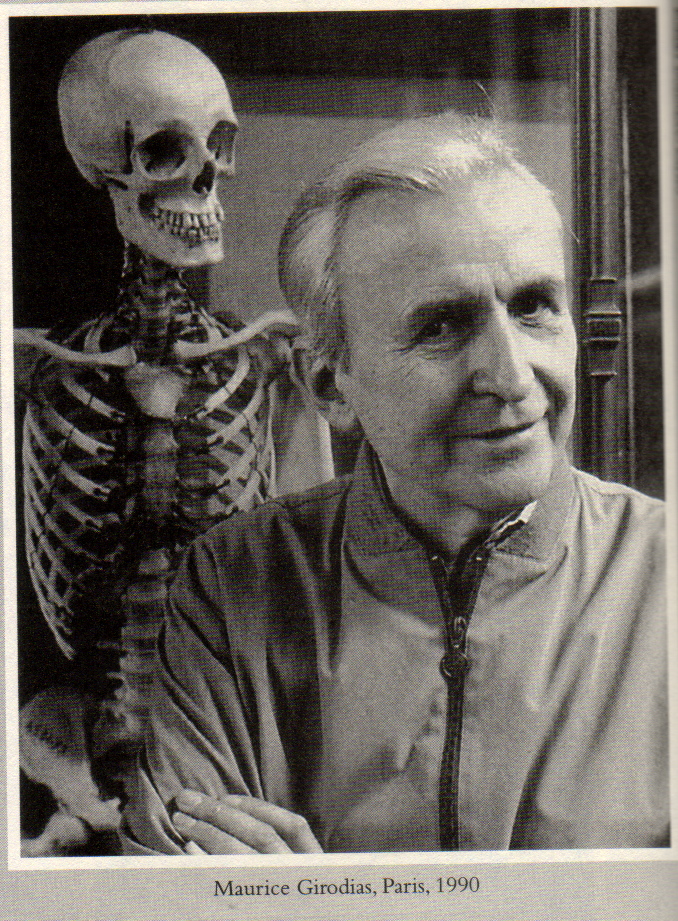

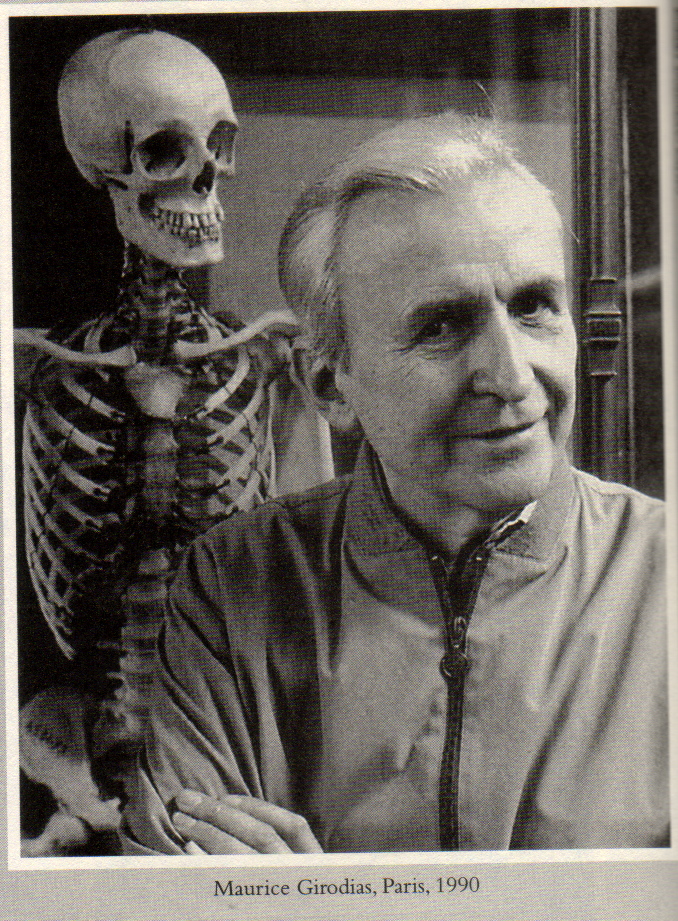

If Maurice Girodias' timing was not always perfect, it never lacked flair, as the absurd rogue genius, visionary playboy-bufoon, and so-called outlaw pornographer and "accursed publisher" proved one last time on July 3, 1991, when he managed to pass away (live) on the radio in his beloved Paris, at the age of 71, while talking about the battles he fought against censorship and plugging the recently published second installment of his memoirs.

Born April 12th, 1919, Girodias was brought up in a privileged artistic and intellectual atmosphere. By the time he was 14-years-old he had not only read Tropic of Cancer in manuscript, he had been commissioned by his father, publisher Jack Kahane, to draw the cover for the ground breaking publication. Before he published Henry Miller his father had published Haveth Childers Everywhere, the first printed portion of Finnigan's Wake, and The Life and Loves of Frank Harris, so the tradition Girodias would follow in was firmly established. After living through WWII in Paris for four years, Girodias started Olympia Press in 1953, in order to publish books in English that couldn't be published in America or England because of censorship. To put the times in perspective, when Norman Mailer�s Naked And The Dead came out in America his publisher replaced the word fuck with the nonword fug, all the way through the book. From Beckett's Watt to Nabakov's Lolita to Donleavy's The Ginger Man to Burroughs' Naked Lunch to Southern & Hoffenberg's Candy, he set a standard that still hasn't been approached today, by publishing books in English in Paris long before their American and English speaking authors could publish them in their homelands.

He found a group of young writers who had come to Paris after the war because that's where Hemingway was in the 30s, and gave them a chance to earn their bones. The late Norman Rubington showed up straight out of the Army to be a painter, and lived in Paris for 20 years before coming back to New York; he wrote four d.b.s all in one year under the name Akabar Del Piombo, and probably changed the direction of his life forever. �My money had run out,� he said. �But I had a scooter and I had somebody who wanted to buy it, which would have bought me a ticket on a ship back to America. It was a sad night, a sad-sad night for me. . .On my way back home from Montparnasse I was driving past a sculptor friend of mine�s place, so I decided to drop in on him. The room was covered with sheets of paper everywhere. He�s sitting in the corner banging away at a typewriter, and he says, �I can�t talk! Read it! Read it! Tell me what you think!� I sit on the bed and start reading it � he was writing it for Olympia -- He says to me, �the thing is, you write 30 pages and if they like it they give you an advance, then you get $500 to do the book.� $500 in those days was like $3,000, $5,000 today. Anyway, when I went home I couldn�t sleep that night. I kept tossing and turning, I kept thinking, Here�s this guy, he�s got guts! Here I am giving up, and here�s this guy he�s a sculptor, right, and he�s gonna do this to make his nut. So I spent the next three days and nights and turned out 30 pages. And I gave it to this woman who I knew who had access to Girodias. I didn�t have a phone in the place - most people in Paris didn�t at that time, but what you could do was go to the Post Office and for about three times what an ordinary stamp costs you could write a letter and a kid on a bike would deliver it. And they�d guarantee it would arrive in one hour. So I told her, you hand in the manuscript, but I have to know by Sunday. Well, the weekend came and went. Nothing. So Monday morning I set out to find the guy who offered to buy the scooter. I figured they had read the manuscript and thought it was shit. By pure coincidence I ran into the girl I gave it to. She was all smiles and everything. And I said �What are you smiling about?� And she says, �He wants to see you.� She had obviously forgotten to let me know. So I go to see Girodias, and he looks at me and asks, �Do you like horses?� I say to myself, �What have I got here, a madman?� Then I remember it�s a line in the book, so we talked a bit more and he told me to get some money from the secretary. When I started for the door, he said to me, �Just tone it down.� And I figured, I don�t know what this means, this is going to blow the whole thing.� It felt like there were clamps on my head suddenly. He must have noticed though, because as I got to the door he said, �Forget what I said. Go ahead and do what you were doing.� �And so in three weeks,� Rubington said, Who Pushed Paula, as Girodias called it, was done. And he was amazed! "All I wanted was my 500 bucks so I could go buy paints, and Girodias says, �Hey Balazac, you wanna do another one?' And I said �Sure.� So instead of buying paint I bought paper. And when I came downstairs from his office the guy, that sculptor was just turning in his 30 pages. Which was later rejected. And so he left, he went to Holland. And had a long, successful career as a sculptor.� Rubington roared, �I mean, you just don�t know, man! It�s the finger of fate! And you never know where it�s going to lead.�

Girodias old friend, British publisher John Calder told me, �Maurice was basically a revolutionary romantic who never felt like getting out of the barricades. For instance, there was one absolutely beautiful story that happened after he was dead broke in the early 70s. He booked himself transatlantic first class flights backwards and forwards across the Atlantic hoping he would run into someone who would back him getting started again. Believe it or not he found someone on the third flight. He met a printer who helped him start Olympia in America." But America brought more turmoil. The day Valerie Solanas shot Andy Warhol, she went looking to shoot her publisher first. Fortunately for Girodias, he was passed out drunk behind his desk, so when the author of The SCUM Manifesto pushed her way into the office to shoot him she didn�t see him lying there. "Maurice basically liked cocking his snoot at authority," Calder laughed. "He liked being a bit of an outlaw. Obviously during the war he learned a lot about the art of survival, and must have been involved in the Black Market in order to survive. He was in bad odor with the police in any case because he was publishing books the British home office detested like The Black Diaries of Roger Caseman, they wanted to prosecute him. I do remember going to court with him once in �67 or �68. He was very white. He was going to go to jail for publishing books against good morals or something. He was trembling in the dock.�

Connected to Girodias through one of his favorite former authors, Iris Owens, a.k.a., Harriet Daimler, I went to Paris to do both an article on Olympia Press for New York Writer, and an interview with him for Smoke Signals. We met at the Pavillon Hotel, in the Paris' Theatre district, and wandered through the small cobblestone streets talking and joking until we come to a small cafe, he found satisfactory. As we sat down to lunch Girodias handed me a copy of a drawing he had done as a boy for his father's Obelisk Press that became the original cover of Tropic Of Cancer, and a letter he wrote to Samuel Beckett a few years earlier that he wanted me to publish as an open letter, since Beckett, like many of his former authors, would not respond to him or his communications personally. Like Girodias' career, the interview goes back and forth between gravity and levity, serious one moment, the next making fun of itself and the situations; an attitude that obviously got Girodias in trouble over the years, but also got him through more than his share of close scrapes. This interview, the last major interview of Girodias' life, took place several days before his 70th birthday, in the second week of April, 1989.

- Mike Golden -

SMOKE SIGNALS: You started publishing in 1939?

MAURICE GIRODIAS: Right. I succeeded my father. My father was British, and came to Paris, and then in the 30s decided to start his own imprint and to publish books in English that could not be printed in America or England because of censorship.

SMOKE SIGNALS:Was your father the only one publishing Henry Miller?

GIRODIAS: Yes, only Obelisk. Though three of his things were bought by New Directions, but New Directions wouldn't touch the Tropics -- that was the whole issue. Before the war, not even two thousand copies of Tropic of Cancer had been sold, you know. It was absurd! But on the strength of those two thousand copies the tradition was already solid. I heard the book business was not at all then what it is now. One million, one million copies of things sold now represents about two or three thousand before the war.

SMOKE SIGNALS: Was that before you went out on your own?

GIRODIAS: I started in that two or three months between the Declaration of War and when the Germans arrived. A period of about nine months where nothing was happening. I got into publishing with a German refuge, who had a small distribution house in Paris. We started a paperback house for English books which were to be printed in France. There was a German outfit, who was publishing a paperback series mostly for British and American tourists traveling in Europe. But those could not be sold in France, so the idea was to take that market over and publish English language paperback books, but not for the tourists, you know, for the troops. And so we started the project but it never came to be because the war was on before we had our first books out. He went to America and \tried to convince me to go with him. I was just 20 and I decided to stay in France; my fate was settled then, because I was half Jewish. At that time I had a British passport and it was pretty crazy to stay in Paris during the occupation. I had my French family, and there was actually no money at all, and I just couldn't leave them like that. So I changed my name, and took my mother's name. And had a fake identity card. I spent the entire four years of occupation straight in the middle of the German operations and nothing ever really happened to me. Once or twice I was questioned. But I got through that. (laughs) So I created out of nothing this French art book publishing house, Les Editions du Chene, which was very successful. I knew nothing about the publishing trade, nothing about business. It was a bit of a miracle. Of course the biggest miracle was that I went through the four years of occupation and nothing happened to me. So I knew that I was lucky, I was a lucky man, I could do anything I wanted, I just had to decide. It was a charmed life. So simple. All my school buddies went into war, you know. Some of them were killed. Others were prisoners for four years. I was against the war. I didn't care about Hitler. The others were not better. He made more noise than the Democracies but I thought that he had his points. Of course what he did with the Jews I couldn't approve, but you know I had cultivated a position of complete freedom and total neutrality and at the time it paid off, but after the war things started to change and I enlarged my activities to novels, fiction, political books as well. I ran into trouble with the government, the first socialist government after the war because I published a pamphlet denouncing the economy. The protection of the Black Market around the world that was very big just after the war. I had a huge court case which the government came in as a witness against us. I won that case, I won that law suit, which was very bad for my future.

SMOKE SIGNALS: Why was that?

GIRODIAS: I was marked. I had a big file on me. I was the next man to go. But I didn't care, because I knew then the luck was on my side. I could dare anything I wanted. Which is a charming, youthful delusion. Which I kept 'till, you know, pretty late. Because then things started getting very tough. My distributors were Hachette, which is the biggest trust for publishing, book distribution, newspaper distribution, one of the big powers in this world, which is unknown in America, but it's a purely French phenomen. They had the control, they controlled everything. After the war they lost their power for a few months. They were kept under very strict control by the Germans. But after the war they very soon got back into power. So they offered me a partnership arrangement. To turn my art book publishing house into something very big, international. I signed an agreement and I found out they didn't mean it. They wanted to take over my firm without giving me anything. And what I had signed was, you know, not well worded. There were loopholes in it. I discovered that I made a very bad blunder. So I was totally dispossessed from my 10 year old publishing firm. But before that I had published in French, Tropic of Capricorn in cahoots with two other publishers, who were publishing at the same time Black Spring and Tropic of Cancer. Because there were rumors that the Socialist government wanted to start censorship in France, which was completely absurd. I mean, a war against the enemies of freedom, you see. It was sort of cuckoo, but that's the way it worked you see. The first action was a law suit against the three publishers of the Henry Miller books in French, in '46, although they had been published freely in English before the war. And we won that case. Then the next thing that happened was the takeover by Hachette of my outfit. I was expelled from my own company, unable to understand or resist that piece of classical capitalistic maneuvering. So I was completely despondent, there was no money.

SMOKE SIGNALS: When was this?

GIRODIAS: 1949-50. For three years, until '53, when I decided to do what my father had done. I was still in communication with Miller and on very good terms with him. So he gave me Plexus to publish. . .George Battille had two or three books that he gave me to publish . . .In '46 I started a review, Critique, which still exists and he edited. Then a book by DeSade, (Bedroom Philosophers) translated by two young Americans (Seaver & Wainhouse) who were part of a whole group of British and American would-be writers-poets who had started a magazine called Merlin. And Dick Seaver was an associate of that group. Alex Trocchi was the editor. Austryn Wainhouse. Patrick Bowles, Philip Oxman, Baird Bryant, Alfred Chester, John Stevenson and John Coleman were all more or less directly connected with Merlin, as was also at a prudent distance, George Plimpton. Iris Owens became an important addition, and Marilyn Meeske. Some of them contributed to the Olympia Press novels which were usually violently extravagant and outrageous. I usually printed five thousand copies of each book, and paid a flat fee for the manuscripts which, although modest, formed the substance of many an expatriate budget. My publishing technique was simple in the extreme, at least in the first years: when I had completely run out of money I wrote blurbs for imaginary books, invented sonorous titles and funny pen names and then printed a list which was sent out to our clientele of book-lovers, tempting them with such titles as White Thighs, The Chariot of Flesh, The Sexual Life of Robinson Crusoe With Open Mouth, etc. They immediately responded with orders and money, thanks to which we were again able to eat, drink, write and print. I could again advance money to my authors, and they hastened to turn in manuscripts which more or less fitted the descriptions.") Those people had come to Paris in the belief that it was still Paris in the 30's. (He laughs) They had heard all the stories of the wonderful life in the 30's, and they thought it was so insane. But when they got here they didn't find any trace of the city. The war had changed it completely. And there were absolutely no English or American writers except them. Those kids, you see, had never written anything, but they all had talent, see, they were all very interesting. They had gotten together because of a similar taste for literature. I mean, they were the first English speaking people to discover Samuel Beckett. Actually, Beckett was first published in English in Merlin. And they had bought the rights of his only book in English, called Watt, but they couldn't publish it, so I published it. And then I published the rest of the Beckett novels, for which I've never been credited in any book. He totally forgot I had been his first publisher after he had been taken over by Grove Press, under disgraceful circumstances. So that really got me started, you see. I had absolutely no money to start a thing right. But I was used to doing things without money. And it was an instant success. It worked like magic once again. And it all happened in five-six years. Naked Lunch was my last big book. Published in '59 - Burroughs. And in between I published Genet in English, people like Chester Himes. In the 60's it was over. The publication of Lolita in '56 was the event. I had my biggest litigation with the French goverment over that. And once again I won the case - it really finished me completely. After that they harrasssed me until I was forced out of business. But in the meantime I had made a fortune with Lolita . It was the only book I ever published which made me temporarily rich. because it was the only book I had a solid contract which the author couldn't break when he became famous. He had to live up to the contract, which gave me one third of the income of the reprint in English or sale of foreign rights.

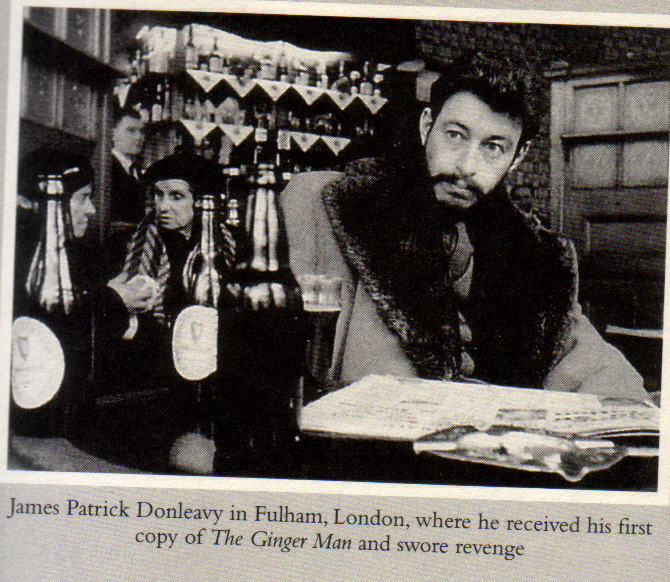

SMOKE SIGNALS: What happened with Donleavy, with The Ginger Man? When did you publish that?

GIRODIAS: 1955.

SMOKE SIGNALS: You didn't make money from that?

GIRODIAS: No, no. The

story of The Ginger

Man is a fabulous story. Much better actually than the book.

I

published the book, I had a contract which was sort of badly worded,

made up of several letters of exchange - contracts were too boring to

write up. Really at the time I didn't expect things to turn out the

way they did. I didn't expect censorship to fall so fast. Censorship

was really done in by the publication of Lolita in

America. As for The Ginger Man, Donleavy gave his

version

many times - everytime he goes to America he goes on the circuit and

gives lectures. Basically what happened was that I had world rights

in the English language and translation rights. The same as Lolita,

but a very weak contract. I mean, you know, Nabokov insisted

on

certain things because he was more professional and older - he

insisted that he wanted a proper American contract. So that was my

lucky break. A fantastic, well worded contract done by regular

lawyers. The year after I published The Ginger Man,

Donleavy

sold the rights again to an English publisher thinking that I was

viewed by the English courts as a satanic character, and I would

never sue him in England where he lived. But I was so angry that I

did. And I got caught in the English legal system. It's quite

incredible. It starts in a very mild way - they offer you a cup of

tea, you know. It looks very innocent, very friendly, and then you

end up having to pay thousands of pounds anytime anything happens. And

little things happen all the time. But the case never goes to

court. So after six years the case hadn't come to court.

SMOKE SIGNALS: Did you have any personal dealings with Donleavy?

GIRODIAS: He came to Paris after The Ginger Man was published to talk to me. I gave a party for him. And gathered all the literatti I could find who might be able to speak to Donleavy - not one of them had read the book - but I had talked to them about it so he would feel like he had a big readership in Paris. But he got very drunk and he left the next day. During the party he spoke to my younger brother (Eric Kahane) who had translated Lolita, and he thought that my brother was me, you see. Or he pretended that he thought my brother was me. I had to carry him home bodily on my back, which fortunately was just around the corner. And the next day he had lunch with Austryn Wainhouse's wife, Muffy, who was my secretary and editor, and had edited his book, and had done a fantastic job with that. She was a very clever person. The manuscript we originally got from him was a complete mess. Absolutely unpublishable the way it was. So he saw Muffy and went back to London. And that was all the conversation I had with him. When I brought him in that (drunken) state to the hotel he said to me, "Are you Girodias' brother?" Which I think was a ruse. I don't think he was that drunk. The whole scene was contrived. And the whole trip had one purpose; it was to convince me that we had had a definite talk about my relinquishing English rights to him. Which never happened. But in his correspondence after that he repeated the fact time and again in order to build up the assumption that I had returned the rights to him. Which is typical Ginger Man technique, you see. I mean the whole story is quite beautiful because it is very inventive. After the English publication he broke his contract with his first publisher, sold it to another publisher, then a third publisher, and in time another publisher, each time exercising a mixture of very interesting gifts he has, you know. . .His power of wasting time, of confusing people. Which is a special gift that he has. He has a good knowledge of law, but a better knowledge of human character. The fact that people won't stand for an impossible situation. For having to deal with him. To decipher his letters and the intent behind each letter. So I really got involved in this thing. This situation went on for years and years and years. It started in 1956 - where I started litigation in England, which he managed to delay and the case was kicked out of court because of lack of action. Which was really (laughs) the most absurd thing that could have happened, but I had a parallel action going on in France. And there my chances were much better. I won the case - but there was an absurd French deposition which gave him eight years to appeal - so he waited eight years to make his appeal. So by then the case was about 16 years old. So finally from appeal to appeal in the French courts I was getting close to a complete victory. Which meant he would have had to pay back to me half of the income he had made from his book over the years plus substantial damages - it would run into a half million dollars at the time, or more. I was sure I was going to win. I had been through several bankruptcies then. With the Lolita money I had started a nightclub, which was called Chez Lolita - but Nabokov sent a letter to his French publishers who I had connected him with in the first place, and they relayed to me they would sue if I didn't change the name.

SMOKE SIGNALS: So you called it Grande Severine.

GIRODIAS: Yes. Because of lack of its rightful name. I bought a building on Rue Saint Severine. In the cellar there was a restaurant with dancing and a Brazillain samaba band, on the ground floor a French restaurant, on the next floor a soul food restaurant and blues bar, with Hazel Scott on the piano, and on the top floor there was a Russian nightclub called Chez Vodka, with a balalaika ensemble.

SMOKE SIGNALS: Sounds like you invented the New York Club scene, 20 years early.

GIRODIAS: (laughs) It was a wonderful exhausting enterprise. Which lasted five years until it was closed by the police. I decided to open this nightclub because I was living at night, you know. It was probably a substitute for a family. I had had a family, but I had abandoned them, so I needed a family, you see. A strange family. I think it really was the most inventive, gratuitous, absurd place that ever existed. It was a non profit nightclub. I sold caviar and champagne for as much money as I could get, but that all went back to the privileged customers who were my friends and the staff who stole everything they could get their hands on ( laughs). It was madness! I slept about two nights on the average and two hours a night on the average, and drank so much that I got totally gaga. But during the last year we started making money. So I got very optimistic once again, and started a theatre in a 13th Century theatre. An experimental theatre. Then I had an idea that I should do The Bedroom Philosophers, which had been sort of the theme of my publishing life. Which seemed to be legal in France as a book at the time. So we created a play that was perfection. It was beauty. But the cops, when they came to settle with me, they sent the Vice Squad, which had tried to get bribes from me since I started my publishing career. I had turned them down, and they never forgave me. So they had a vendetta on me as well. And since I was winning all those cases against the government, when I started the DeSade play they made that my final defeat. I was put away for five days. Not because of the play itself, but because of some nonconformity to regulations in this or that. My creditors couldn't stand the shock of it and I was bankrupt in a few days.

SMOKE SIGNALS: Were you still operating Olympia?

GIRODIAS: Yeah, but Olympia was not doing much. Burroughs books I published in '61-62. A strange book by Gregory Corso called American Express. Things like that. Reprints. But by opening that nightclub I had missed the boat completely, you see. I should have gone to America in 1960.

SMOKE SIGNALS: Donleavy happened in '56. What happened to The Ginger Man?

GIRODIAS: Oh yes, there is a sequence to the story. It is 1970, 1970 when I'm about to win the case against him - I've been bankrupt several times in France, but I'm in New York with a remake of Olympia Press. Which is not terribly inventive. But for the first time in my life I'm comfortably installed in the situation of a millionaire publisher. I go back to Paris from time to time, but I cannot recognize the city as my own. I'm a big American publisher - I'm not big really, but I have money and I can buy anything I want when I come to Paris. I can stay in the best hotels. I'm totally deluded by this American thing but I'm so completely taken by the conclusion of the Donleavy story - and I'm getting close to it.

SMOKE SIGNALS: This is New York Olympia?

GIRODIAS: No, no, Free Way - Olympia doesn't exist anymore. It's been bankrupt for years. But in spite of the bankruptcy I've managed to keep the case against Donleavy going through a receiver who I've bribed everytime I come to Paris. I deliver a big hand full of banknotes to him, because it's not quite legal but is still. . .Donleavy can do nothing against it. Donleavy is being sued by a phantom company which does not exist anymore. Legally, because legalities are essential (laughs), we've reached the point where we're going to win the case, but the company which doesn't exist, doesn't belong to me anymore. And I have to manage to get back the phantom assets of the bankrupt company from the receiver, to buy them back, in order to benefit from winning the case against Donleavy. You understand the intricate situation (laughs)... And this is a half million dollar issue in 1970, when a half million dollars is worth much more than today. . . So I bribed the receiver some more to organize a public sale of the assets of the bankrupt compnay, to be the buyer of the company, and to do it in such a secretive manner that at this public auction I should be the only one to be there, nobody else should know about it. It is done in such a way that the legal publicity for it is immediately torn down from the walls. So when I go to the auction after lunch with my legal advisor, the Swiss lawyer who's agreed to the money, there are a group of people there who I didn't expect to find there. I think they are tourists who have lost their way at first, but then these people start bidding against me! I wasn't prepared for that, you know. I could only go as far as the money I had on me. That was $8,000, which was double that amount because of the court expenses. So I had to stop bidding - I looked at the group of three people which were bidding - the man was obviously a Paris lawyer, and the two women were obviously crazy American ladies. I couldn't understand who would do this, you see. Who would that benefit. I thought it was a silly rich American girl who wanted to have the name of the company and then make an offer to me to run the company - an Ann Getty situation - I didn't know. So I started thinking about it and looking for answers, accusing some people of being behind it. You know, I got into a great deal of trouble at that time. And then I discovered through the lawyer that the woman who had bought it was Donleavy's wife. (laughs) I think it is one of the most beautiful, romantic legal or legal romantic stories of all times. Donleavy bought it. And I respect him for it. I have heard he is writing a book about it. That was 10 years ago, but in 10 years he has not found a way to bring out the story. I am willing to write the story with him as a dialogue, but I'm sure he won't do it. The Ginger Man is a good story, but this is a better story.

SMOKE SIGNALS: You've never heard from him again?

GIRODIAS: No. Not since I carried him back to his hotel. The Esmerelda.

SMOKE SIGNALS: Truly amazing.

GIRODIAS: There are lots of stories like that in my life, but I can't write them.

SMOKE SIGNALS: Why not?

GIRODIAS: I can't get it out. The first autobiography (The Frog Prince) was easy to write. I wrote it in three and half weeks. And this one I've been at for 12 years. I can't find the right tone. The last attempt in French I have come close to it, but. . .

SMOKE SIGNALS: You have a contract for it?

GIRODIAS: Oh I have so many contracts, I have changed publishers so many times, but my position now is that I have to get away from this thing. Which I have done for the last six months. It's two thirds done. It's not bad, but I don't feel it has the movement of the first volume. It was more innocent and childish, but the second one of course is savage and dense and terrible in many ways. It is also very funny and dramatic at the same time...

SMOKE SIGNALS: Speaking of drama, I'd like to talk a little about Candy. What happened with Candy?

GIRODIAS: Oh Candy! That's a stab in the heart!

SMOKE SIGNALS: How does that stab you in the heart?

GIRODIAS: Because it was a disaster. But in much bigger proportions. For everybody. Terry, Mason, myself. . .

SMOKE SIGNALS: And now Mason's dead.

GIRODIAS: Oh yes. . .Not that dead, but he is dead. He is legally dead. Mason was my baby, you see. We had a particular father-sonny relationship. (laughs) Mason brought Terry in, who was an innocent living in Geneva, which he at first thought was Paris. He had landed somewhere in Europe, he wasn't sure exactly where. Mason and Terry were buddies - Terry was the first one to try to express himself in writing. Poor Mason was a jealous man, you know. He was born jealous. Jealous of other people's talents. That was what was wrong with the Candy business. Mason did it, not Terry. Terry was another type of innocent. They were both innocents. Why Candy took two years to write was Terry was living in Geneva, and Mason in Paris, and so commuication was difficult. So the book moved very slowly. But I'm not the one to criticize slow moving books. . .

SMOKE SIGNALS: Did you pay them an advance or a salary to write it?

GIRODIAS: I paid them an advance. It was piddling money. The rate for dbs as we called them, had reached at that time, $1,200 to $2,000, which was not so bad. With most of the writers I worked that way because that was the only way to get the pages, you see. To the end.

SMOKE SIGNALS: It is motivation, no doubt. You get half now, half when you turn it in.

GIRODIAS: It is not a motivation for me. It doesn't threaten me any more. I don't believe in it. I never believed in money. It was never a motivation, but what probably ruined me, somebody told me once, was that I hated money and despised money, and money hit back, you see. It was a wise Jew who told me that, and he knew what he was talking about. And he was right. I had money, I had money, it was either money or me. Yes, well you see I was born with a father who had a sense of business. He would never have done all the foolish things with money that I did, but at least he was responsible and he had an organized mind. But I didn't get anything from him. You know I never knew what I wanted to be, never knew how to speak to him, and he didn't know how to speak to me, so we never talked. Though he was a perfect example for me in terms of aesthetics. His taste in women was wonderful, taught me a lot, because when I was 14 I read Tropic of Cancer in manuscript form. Then he commissioned me to draw the cover - we had that kind of communication. But apart from that we never exchanged more than 12 sentences in our entire life together, which lasted 20 years. And I worked for him the last six months of his life. That's where I started making books. (He suddenly changes the subject) I wonder about the writers.

SMOKE SIGNALS: Why do you think Trocchi was so self destructive?

GIRODIAS: He wasn't that way. There was an imbalance in him. There was an imbalance in each one of those young fellows. He had that lack of knowledge about himself, which made him more brash, more more more, he could do everything, he could cover the ground entirely, no one could teach Alex anything. He didn't go that far. The drugs of course were a short cut for all the problems he couldn't confront, and that didn't help.

SMOKE SIGNALS: He was Frances Lengel?

GIRODIAS: Yes.

SMOKE SIGNALS: Who was Akbar del Piombo?

GIRODIAS: An American painter, Norman Rubington.

SMOKE SIGNALS: And Marcus Van Heller?

GIRODIAS: (hesitating)

SMOKE SIGNALS: Is it still a secret?

GIRODIAS: John Stephenson. I don't have any secrets anymore. The contract was that I was to protect their anonymity completely because they were taking big risks doing what they were doing. They would have been kicked out of the country immediately if they had been found out. So I was supposed to have been the author of all those books. A set of them. 20 books a year. When I went to court I had to claim that I made them. Very simple - and they would threaten me with three months in prison for every book.

SMOKE SIGNALS: Did you actually ever go to prison?

GIRODIAS: If I may say, twice one day. But I managed to get out by the end of the day. By the one telephone call allowed me. I had a very good lawyer in those days. And it was just a question of timing. Twice I was caught and I thought I had had it, since I carried this total of so many sentences over my head. If I was in prison by the end of the day, then I was there for six years, you see. (laughs) It was quite serious. It ended my priviledge. That priviledge was the result of incredible calculations and dates in which you should do such and such a thing.

SMOKE SIGNALS: You've spent a good deal of time with lawyers.

GIRODIAS: Oh yes. Yes, I spent 25 years, not just in France, but in Holland, Italy, Germany and Japan. In the 70's when I was rich man in New York, I started building a world wide Olympia Press empire, creating branches everywhere. I even tried Turkey and Finland, tried the Soviet Union through Finland. The French version of the product, which had been born in Paris in the English version was completely upside down. The books were banned world wide. Although I lived in crazy times I consider myself as very sane. Reasonable. Sensible. Full of craziness (laughs).

SMOKE SIGNALS: That time seems full of passion. A passion that doesn't seem to exist today.

GIRODIAS: It was fantastic! Fantastic! Everybody's life was reinvented in it. Even George Plimpton's. He was in Paris, ready for anything. Fortunately he had the idea for the Paris Review. That was an excellent thing. I lost touch with him over the years. I mean, he tried to write a db for me. Cheew! The pits. Impossible! And writing was really the thing then, not like now. Painting became the thing later, you see, and earlier, before the war. But after the war one generation was on the way to extinction. Picasso was still alive, but imitating himself. The last breath of fresh air in this country came externally. France cannot exist all alone. So what happened came from outside.

SMOKE SIGNALS: Let's go back to Candy, for a minute. I don't quite understand what happened there.

GIRODIAS: Candy, uh. . .Candy is a story having to do with the law, the copyright law in particular. And the American copyright law, and that particular clause of the American copyright law called The Manufacturing Clause. Candy was under the copyright of Olympia Press. That copyright could have been enforced in America, if the fiction of the situation was lived up to by the writers, that they were writers for hire. The real author was the publisher who invented the story. Millions of dollars depended on whether Mason and Terry understood that fiction. Had they agreed to it we could have protected the copyright in America. But they couldn't accept even in theory that I would be considered the author of the idea of Candy. At this point I was getting into a dispute with Walter Minton, the young President of G.P. Putnams. He had bought Lolita after Rosemary Ridgeway, who was a dancer at The Latin Quarter, told him to. She had apparently read a copy of my edition in New York, and she was apparently bright enough for a dancing girl to find it a great book. And got Minton interested in it. He was more interested in her than the book, but he bought the rights from me. Which became possible because a copy of Lolita had been sent to America. The package was opened by customs and they sent it on to this reviewer who wrote to me to indicate the incident, since he found the name of Irving Fishman, the officer who had opened the package inside. He suggested I should write to him, which I did, and this man wrote back and said that indeed the book had been examined and found acceptable in the United States. And because it came from the Customs Bureau, it meant that no ban on Lolita could be imposed anymore. It could be imposed locally but the Supreme Court would quash it completely. So this opened the way for Lolita to be published in America. On legally safe ground. Which is why it was the first book I was able to sell, based on my contract with Nabokov. So this was after the book was published and it became a best seller for Putnams that Minton came to Paris for the first time with Rosemary to consumate a piece of business with her. He was a married man with kids. So he took her to Paris with him and there was a horrible scene. I asked them when they arrived where they wanted to have lunch. Rosemary picked the most expensive place in Paris. I didn't have the money but I was forced to do it. It was a totally grotesque lunch, when she forced Minton to admit he had never read Lolita; the ultimate humilation scene. In the evening we met again and I asked Iris Owens to come with us to help control the situation. We went to a lesbian nightclub where Walter and Rosemary continuted fighting. At one point it came to fisticuffs. Walter tried to punch Rosemary. Rosemary took Walter's glasses and threw them on the dance floor. Things like that. And the next day Walter had left and Rosemary was in my bed. It got more and more complex. After that I made Walter a rich man as I usually do to people. He was not very good at publishing, but he listened to that girl on that occassion for other reasons, but it paid off immensely. Putnams was not in good shape at the time. But then there was a time he was trying to do me in. To buy books that could be stolen from me. You know that had a sort of shakey copyright. Or he could seduce the authors. And you know he found those two nitwits, Mason and Terry. And he bought the rights from them for $1,000, with a contract which said "If ever after being published by Putnams Candy would be republished by another publisher in America he would stop paying royalties. Even for whatever he had already sold of the book. They signed that contract. Those two imbeciles! And this is of course what happened. Because I had the only possible legitimate copyright, if they agreed to the humiliation of accepting they should be writers for hire, which they were in fact, writers for hire, because they were working on a salary basis in Paris. And I would have always given them the copyright, not disputed their rights of authorship, but it was an assumption we had to take because I couldn't use their name on the Paris version. That was our arrangement, that I had to protect their anonymity.

SMOKE SIGNALS: They didn't write it under their names? What names did they write it under?

GIRODIAS: Maxwell Kenton. That was the first edition, which went on for a few years, until the American edition came out of those duel names.

SMOKE SIGNALS: What were you paying them?

GIRODIAS: A thousand dollars.

SMOKE SIGNALS: I mean, per month or week.

GIRODIAS: I don't know. One or two hundred dollars. Something like that. It was divided over six months, normally, but this took much longer to finish. It was a fair, regular contract. At the time no one saw that it would have the American extention. It was a fairy tale! Fairyland. One thought that in the next century maybe censorship would breakdown. Nabakov tried to publish in America and was laughed at by the American publishers. It's funny today that Americans don't even know that censorship existed 20 years ago. Just as bad as Soviet censorship. There were 30 to 50 different editions of Candy at one point and Publishers Weekly said there were 12 or 15 million copies sold. The biggest bestseller of the time.

SMOKE SIGNALS: That no one got paid for.

GIRODIAS: No. We managed together through the lawyer Leon Friedman to get Lancer Books, who were the first pirate, to pay us a few thousand dollars, which we had to divide between the three of us. There are millions of pieces of paper on this. Leon is teaching copyright law now. He got famous from it, though I'm no richer for it. Terry at least got started as a writer. And Mason, well Mason. . . He was in Paris, you know, and I had that fantastic nightclub, and he would stand on the sidewalk across the street and stand there for hours and hours and hours looking at the people coming in and out. You know, watching the place, and hating me for the fact that I was displaying all those things which he felt that he contributed to. That was before Putnams but after the publication of Candy in Paris. One day he walked into the nightclub. There was a bar at the entrance where I was usually sitting and getting drunk. And he sat down next to me very quietly. And I said, "Hello, Mason." And he said, "Do you have a pen?" So I gave him my pen, and I turned around to the woman I was talking to and when I turned back to talk to Mason he had gone. I asked the bartender "Where's that fellow with my pen?" And he said, "He just walked out." Well, this is just what I imagine, but at that point he signed a contract with Walter Minton. And I think he needed my pen to sign that contract. (laughs) So that is the story of Candy.

SMOKE SIGNALS: Incredible.. . .And all this centered around the nightclub, which ultimately was your downfall.

GIRODIAS: Yes, but it was the most lavish, amusing, inventive place ever, if I say so myself - of course I discredit my own words, but it's a fact. Everybody agreed at the time. But nobody really paid attention to it, because it was too much you see. You don't argue about the Taj Mahal. You see this thing was a constant invention, because I was never tired of it. I added to it all the time. I changed rooms. Brazillian became Russian, and Russian became something else. It was a complete failure for the first year of its activity until it was destroyed by fire. I should have picked up the insurance money, which was very little because I had very bad insurance. I had forgotten about that mistake in my professional career. But being stubborn I reopened after three weeks, you know, with a totally different decore - temporary decore. Then I started totally rebuilding the entire thing on three different levels. Ten different rooms with different themes. I had Hefner's people coming in to spy on us. This was before the Playboy Clubs. It was really unique - we had the greatest jazz of the time - the best people, we had a real Russian nightclub called Chez Vodka. The theatre was gorgeous. I always had at least five or six orchestras and at the end we had at least 70 people working there. It was very elaborate.

SMOKE SIGNALS: What years was this?

GIRODIAS: 1959 to '64. Five years. At the end it was terrible, but it was so funny at the same time.

SMOKE SIGNALS: How did it end?

GIRODIAS: The Paris police closed it because of the DeSade play. It was the silliest excuse ever, but it was the end of this long feud between us. They were enraged because I was not a publisher anymore. I had become a nightclub operator, and a clean one. I didn't sell drugs. There was no white slavery. It was truly elegant, with all the richest people. So a fortune gone. . .

SMOKE SIGNALS: A rich life though. That part's not in your autobiography though..

GIRODIAS: Not the first volume, which was published by Crown. A disgusting outfit. And I had what could have been a reasonably good contract if they had done anything with the book. They thought they had bought a dirty book. They didn't know what to do with it. They had an option on the second volume, but instead I got a contract with an outfit called Poseidon Press. Which is run by Ann Patty, an ex editor of mine, when I was in New York.

SMOKE SIGNALS: That was Olympia?

GIRODIAS: New York Olympia. It went bankrupt after five years of millionaire days. I fired my partner, on the business end, because I couldn't stand his looks or something. At that time we were about to kick the bucket. I was totally foolish. I couldn't stand the fellow, so I got rid of him and three months later I was bankrupt. And then I started again. I started a thing called Free Way Press. In a funny triangular building on 23rd street. The Flatiron Building. Where everything was triangular, which added to the confusion. A very strange building. We had a debt collector next to us. The next office. He came to us to be nice, and asked us if we would give him our business, but three weeks later he was back and saying he was going to collect for some printer we owed. That was really the last. Then we were fired from the Flatiron Building for not paying the rent, and went from degree to degree. But there is still some triangle, three of us working together, but not even publishing books anymore because there was no money to pay printers or authors anymore. So Ann Patty happened in that dying situation. And we stayed good friends over the years. So three years ago we signed a contract for Volume II, with a $25,000 advance, of which she gave me half. And I didn't write the book, you see. So I placed myself in a really impossible situation with somebody who had been my disciple. Just like Socrates does something crooked to Plato. Nothing can really happen. And it all got really disagreeable, you see. I've been back in Paris since 1980. I've been through horrors in this country because I came back a completely broken down man after years of litigation in America to resist deportation. You see, I had this Free Way Press episode, which I found the greatest idea of the century - this was '74, which was to write this book on President Kissinger. Henry Kissinger becoming President for the Republicans in 1976. At the time when the constitution was going to become altered to allow him to become the candidate. There was talk about this at the time. And articles. Which gave me the idea of doing the first political-fiction book ever written. Which was written by four bodies and myself in three weeks. And the book was published, but I didn't know at the time that because of a book I had published two years before on Scientology, I had been written down by the Church of Scientology as a man to destroy. My secretary was a spy from the Church, whose job was to destroy me. So she was busy sending out poison pen letters day after day to bankers, authors. . .One of those poison pen letters was sent to Henry Kissinger just when the book was ready to come out. And it was not a bad book. It was pretty crazy, pure fiction, but it was well constructed, the history was correct, the fiction was all right, the sex was moderate. I mean, we had put in a little bit because of Henry's reputation as a lady killer. And one day I was called by the Immigration Service. I had a French passport at the time, with an open Visa, that didn't have to be renewed. It allowed me to do business as well as live in America. It was not a green card. So when I got to the Immigration Service they asked to see my passport and I give it to them, not expecting anything that bad. And they come back 10 minutes later with the Visa cancelled. "Well, buddy, how long do you need to leave the country? You're not wanted. Your Visa is terminated. Would two days be all right?" So I obtained one month, trying to explain I had a business, I was paying taxes in America. But they didn't care. I mean, he didn't care. It was one man. Who the next day gave an interview in Newsday, telling the whole story as I am telling it to you now. Saying that he had received instructions from Washington to kick me out. He thought I was somebody in hiding and he had been surprised to find me in the telephone directory. And so I got married to the woman I was living with. Who was the daughter of an ambassador. And after that when they found that I had countered their move, they couldn't beat it because there was no suspicion that the lady might be doing it for money or anything. After that they planted, I mean, the same secretary, who I didn't yet suspect, brought me a woman who she said was very interested in my case. She was a very convincing creature, who said, "Well listen, I can resolve this. I and my step father have the connections. We'll solve your problem." We were supposed to have dinner the same night. We went to Newark harbor to check if her stepfather's boat had arrived, and you know we drove into the night in her sports car and arrived there in pit darkness at the warf. And didn't see any boat. So she said, "Let's stretch our legs." We got out of the car, and she said, "Can I hug you?" I found myself locked in a grip, you know. She was as strong as a wrestler. She was much bigger than me. I was sort of losing my breath, and all this happened very fast. At the same time a hand taps my shoulder. I find a cop with a walky talky, who says, "You're under arrest." The girl vanished. He called for reinforcements. I was cornered by three cars full of cops, like a grade B movie. Headlights pointing at me. I was thrown in a car and searched. And you know they found grass in my pocket. Which wasn't there before. Of course she had planted it there. And I was thrown into jail. My wife, we had been married three weeks; she had done that to protect me, and in the meantime we had really become a couple, see. And we still love each other. And we live 3,000 miles from each other, but it was a totally romantic business. So she has to find a thousand dollars to get me out at three in the morning. So she finds the money but another group of Immigration cops from Newark show up and arrest me again.

SMOKE SIGNALS: Before you got out?

GIRODIAS: Before I got out. I don't know about the legality of that action, but the next day they set me free. But after that I had three years of litigation.

SMOKE SIGNALS: Which was in?

GIRODIAS: '74. It was the end of the John Lennon case, and I had the same Judge. He was a hatchet man for the Immigration Service A totally corrupt guy. And I only got out three years later by bribing a Judge in Newark where my drug case was to be judged before they were to make a decision about my staying or going. A difficult life... So my publishing house totally exploded. And I was living off my American wife, who was a medical student at the time. She's a doctor. Lylla Lyon. We are still married. Brutally interrupted. We never found anything to replace it. So that was the end of America for me.

SMOKE SIGNALS: It seems like you have a life story every 10 years.

GIRODIAS: You understand how hard it is - the Encyclopedia of Misfortune, and trying again. The last eight years in Paris did not go very well. The accumulation. Even when I arrived in New York it was at the end of a terrible time in Paris. Endless horrors. So I was tired. I should have taken a rest, but I had to punch back into the fray immediately. So the last episode, after the Scientologist-Kissinger episode, and the investigation that followed, I really broke down in Paris, and I didn't realize it. My last active time was my last two years in America. I was in Boston, where Lylla was working as an intern in a hospital. I was all alone in that silent city. Which was good for me. And after that I left the whole scene and came back here. And here I really broke down. But I didn't know it, you see. I was incapacitated, I was paralyzed. I couldn't finish anything. My not finishing my book is part of that.

SMOKE SIGNALS: You have no inclination to finish it?

GIRODIAS: No. No. . .No. I have to be quite honest about it. I mean, this book is on several levels you know. If I were to write it correctly I should write it as the bible, you see. I should be serious. Writing the history of mankind, and creation, and what not. But I can't do that, see. I'm just a broken down ex-publisher. So that scene of a broken down publisher bores me to death. I've known it, I've seen it, I hate having to write about it. I can do it in a funny way, but that doesn't do justice to it.

SMOKE SIGNALS: Sounds like it could be one of the great autobiographies though. Like Ben Hecht's Child Of The Century or Harpo Speaks.

GIRODIAS: Harpo Speaks! I published that in paperback. Free Way Press. Maybe I don't have the distance to do it yet. What I've written is ok. Some funny stories. (We get up and leave the restaurant, then stand outside looking at the slow drizzle coming down on the cobblestone streets) The entire paraphernalia about bribing the receiver in the Donleavy case, for instance. There was a trip to Holland with the money concealed in my shirt the day before, because I discovered there was a huge amount of French money on me, you know, and I had to go to Holland from Paris, but I remembered that I'm still a French citizen, and there's a law about getting out of the country with any sum of money more than a pittance. I had this fortune on me, and I'm totally drunk as usual. I'm in the Taxi on the way to the train, and I realize I have this money in my pockets, and at the customs I am going to get into trouble, as usual. So I stuck it under my shirt. And I reached the train just in the nick of time. And I sit down, totally exhausted. And I feel a bowel movement. I have to. . .A nightmare. I sit down and there's an immense relief of being seated, and at the same time letting your bowels express themselves. I am sort of dazed, and looking behind my thighs and I see the Sistine Chapel with shrapnel explosions. . .I don't understand what I am seeing, what I am looking at, and I discover it is all those banknotes which have fallen down the shirt and have stuck themselves around the hole, you know, from the humidity. This thing is over the rail. When I understand this I break into immense laughter, and wake up from my daze. I try to get up, you know, and there is a washing thing there, and so I take my pants down and wash my dirty bank notes. You know, my dirty money. Which I do as best I can, and I wrap it in a bunch of Kleenex and put it in my pocket. I have an extravagant experience in Amsterdam, and get right back to Paris. The next day I am sitting in front of my receiver who I always bribe when I come to Paris. And the next step is the Olympia auction sale. So this last time, I bribe him with the notes I have in my pockets since the incident on the train. And those bank notes are still smelly. . .I don't know where cause and effect combine in the prodigal incident.

SMOKE SIGNALS: I think it stupefies physics.

GIRODIAS: (turns to me as we get up and leave the restaurant, and confesses) But my biggest mistake was not Donleavy, you know. It was your friend Iris (Owens). I could have made her into a big-big star. She could have been something, if I had only, you know, taken the time. . .It was really Iris I loved. . .No! What am I talking about? Am I mad? I hate the bitch! But of course I love her too. . . Not as much as I hate her� perhaps. . . but...(Girodias shrugs as we step out into the street, then turns away from me and walks off alone, still arguing with himself.)

From a distance, his feet appear to be separated from his head by the thick mist, so it looks like he�s going in two different directions at once. Ideas and movement; the marriage of insult and injury, lighting up all those mistakes forever on the big board, blinking on and off, on and off, a walking contradiction in terms, coming together and dancing madly with each other in the ether before what�s good and beautiful and courageous is interred with the bones. Or as Donleavy might have said,

Who owns the rights

to the law suit

after the law suit is over?

� 1989-2008 Mike Golden