New York City

I first met Canadian renegade artist, Richard Hambleton in early 1981, a short while after a series of enigmatic posters started appearing in conspicuous places in the Soho and Tribeca neighborhoods of New York City. The wheat-pasted photographic posters of a white man standing in a grey suit and white shirt in a Napoleonic stance, glaring directly at the passersby were definitely something new. They were very disconcerting to say the least. You would undoubtedly ask yourself the following three questions; “who is this man?” “why is his picture plastered all over the place?” and, “why is he starring at ME?”

These were typical reactions especially during the post Punk and New Wave years of 1977-1983 in New York where every square inch of vertical real estate was covered with posters for music and artist performances, poetry slams, comedy acts, political forums was the early stages of what we now know as the “East Village” sensibility. Even in the midst of all the chaos, the strange “Business Man” posters stood out.

Hambleton’s first attempt to crack the hardcore New York art scene realized some success, because he managed to catch everybody’s attention. His posters where different from the usual glut, they had no text, they didn’t advertise anything, or any place, or any event, or any product except, himself, but the public didn’t know it yet.

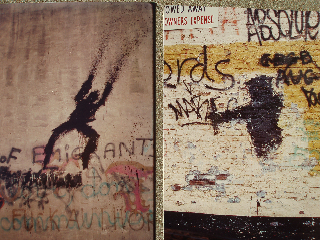

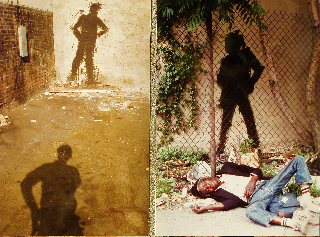

Richard Hambleton would travel incognito for the first year or so in NYC. I felt somewhat privileged, because whenever I would see him, he would speak to me in an almost inaudible sotto voce as if he was a fugitive who just broke out of an Art Prison from some far off country, (Canada?). He went on to tell me of his next venture for Gotham’s city streets, and this one sounded more original than the last. He was going to paint flat black life size figures directly on the walls of New York, during the night so he wouldn’t get caught. He was determined not to get caught or arrested as a vandal or graffiti writer, graffiti artist was not an accepted title in 1982. He wore all black clothes, with a long cape-like black coat to hide his one paint can and one brush. He would strike not at random but in carefully calculated spots that would deliver maximum impact to unsuspecting pedestrians, such as at the beginning of a dark alley, a portal around a busy corner, jumping out from behind a dumpster, etc. The paintings would take only about 30 seconds to complete. They were all silhouettes ,fresh, fast, semi-abstract, expressionistic, Franz Kline-ish in their bold wide Zorro-like slashing strokes. They were all tall and looked like Sentrys, guarding the mean streets. They were male, either frontal, three-quarter or profile. Their arms at their sides, or arms on hips or one arm raised as if in a kind of charging gesture. The later ones were more animated and were scene jumping and leaping 10 to 20 feet into the air, in this case up the wall, and at times they appeared as twins with their heads exploding in unison with a large 10 foot plume of thick black blood gushing from the tops of their necks. Sometimes, even 30 seconds was too long to be caught painting in the street. If a cop were cruising near by, Hambleton would stop in mid stroke. Some of the unfinished figures are the most haunting of all. They tended to look like victims caught in a horrible war where they were burned beyond recognition or had been Napalmed with limbs missing or just hanging off the wall.

Were the figures metaphorical portraits or perhaps self-portraits telling everyone, ”here I am America!” Were they the bogeyman?, were they everyman ? They were different things to different people. To artists they were very cool. To art collectors they were something to have. To gallerists they were something to exhibit. To the police, the city and property owners they were illegal and criminal, and to a photographer they were something historic to document. The painted shadows were anonymous yet specific. They were scary yet graceful, they were illegal yet priceless. They were temporary but yet would leave an indelible mark on your brain. Once you see them you never forget them. They were brilliant!

I soon became somewhat obsessed with Hambleton’s world. He would tell me in advance where he was going to strike next. I felt like a lucky scoop reporter for a News Daily excited about my next new breaking story. I wanted to know where the figures were going to be painted because I wanted to capture them fresh, new, all black and unadulterated. In New York nothing is left alone for very long and almost immediately other wanna-be street artists would add their pathetic little tags on top of the Hambletons. However, in the beginning, before the general public caught on I was able to capture many clean black figures on color film, color slides and in black & white. All this was familiar territory to me because at this time I had already photographing walls and had spent several years photographing street art, graffiti, murals, etc., so this was right up my alley. In fact, I had just come back from a month-long trip through the People’s Republic of China in 1981. I had a color photographic book published entitled, Great Walls of China. This book records walls, murals, posters, billboards and signs of post-Mao China, a very different China then from what we are familiar with now. My book is like a time capsule of this transitional point in China’s history from Communism to unabashed Capitalism under the guise of Communism.

Also, in the mid 1970s I photographed some of the earliest photos of the wall graffiti by Samo, who later became better known as Jean-Michel Basquiat.

As time went on, I had photographed dozens and dozens of Hambleton shadow paintings. After several months, I noticed a whole new crop of street art had spawned along side of Richard’s silhouettes. I was no longer annoyed by the visual intrusions of others and began photographing all the ancillary scribbles, doodles, cartoons and words attached to the black figures and all the components started taking on a life of their own. Richard’s brooding dull black house paint gave way to day-glo pinks and oranges, skeletons, telephones, living room furniture, red evening gowns, happy faces, guns, whips, dogs, scarecrows, you name it. The whole series started looking like a cult gone wild!

While Hambleton was getting fantastic press coverage, he was still a mystery. He made me promise not to give out his name or telephone number and I kept my word. Eventually, the press caught up with him and he was an instant

Art Star!

For weeks and months he was on every body’s lips. Everyone also had personal stories attached to the figures, like when they turned a street corner, seeing a Hambleton shadow would scare them to death and at times elicit a scream! I think that was part of the clever master plan. Play off of New Yorker’s fear of crime and creepy people and you are guaranteed to get their attention.

While the New York Press was catching up to Hambleton in New York, Richard was already roaming around Europe doing the same thing. There are black figures in London, Amsterdam, Paris, Berlin, Rome, Milano and other cities. I managed to find and photograph a few in Europe several years after they were painted. On a stroll through Tompkin’s Square Park in the early 1990s I found a Hambleton I missed the first time around because it was painted on a tree. I just didn’t think to look there.

I was the first artist/photographer to compile the Hambleton wall paintings into book form. Subsequently years later others did the same, such as the Europeans and the Japanese. However, my original 200 signed and numbered handmade books were included in many exhibitions and artists books venues such as Printed Matter, Franklin Furnace, Center for Book Arts, Exit Art, Pratt Institute, New York Public Library, Bergen Museum, Moore College of Art to name a few and are in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art Library, Brooklyn Museum and the Houston Museum of Fine Art to name three.

Over the span of five or so years I photographed approximately 120 black figures and have produced a color and black & white laser copy books of about 45 of the best figures. They were in editions of 100 and 200. I have a few b&w copies left. I plan to update and make a new color laser edition of NightLife in 2008. Now you know where the title comes from.