THE LOVED ONE

an excerpt from

TRIPPIN’ WITH TERRY SOUTHERN:

WHAT I THINK I REMEMBER

by Gail Gerber

with Tom Lisanti

an excerpt from

TRIPPIN’ WITH TERRY SOUTHERN:

WHAT I THINK I REMEMBER

by Gail Gerber

with Tom Lisanti

Hollywood, summer of 1964. I had been living in California for almost a year now and still felt like a fish out of water. Growing up in Canada where I studied ballet from the time I was a small child, Los Angeles was mystifying to me with its palm trees, bright sunlight forever contrasting with the deep shade, and its superficial inhabitants. But I readily admit I was sort of a snob myself and didn’t know much about the actors or directors I came in contact with. Petite blondes like Sandra Dee were the reigning young actresses of the time but I couldn’t tell a Sandra Dee from a Tuesday Weld from a Connie Stevens. They were all one big yellow-haired blur to me. And forget about pop music—the minute The Beach Boys or Connie Francis would come on the radio I’d reach for the dial in a mad rush so as not to hear their insipid songs. The dance and jazz worlds were where my interests and background lay.

Arriving in town with my unwarranted bias and without knowing a soul, I had done pretty well for myself, or so I thought, in a short period of time. I had a leading role in a play, two featured movie roles albeit in teenage B-movies, and had done a few guest TV shots. I knew it wasn’t solely my acting talent that was landing me roles. I was a pretty blonde with a shapely figure that looked good in a bikini and wasn’t afraid to show it off, which helped me tremendously. It didn’t bother me in the bit, unlike actresses who I regularly came in contact with, that wanted to be known for their talent rather than their looks.

In August 1964 I found myself back on the MGM lot, after working there previously in the Elvis Presley musical Girl Happy, auditioning for a cameo role as an airport information girl in a big major production. I was very excited. The movie was The Loved One based on the novel by Evelyn Waugh and directed by Tony Richardson who was the hot director at this time. Part of that British “New Wave” of directors in the late Fifties, Richardson directed such well-received movies as Look Back in Anger (1958), A Taste of Honey (1961), The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962) and the hit bawdy comedy Tom Jones (1963). The Loved One was his second U.S. production.

I interviewed with associate producer Neil Hartley, the boyfriend of Richardson who was bi-sexual though married to actress Vanessa Redgrave since 1962. Folks in Hollywood used to joke that Tony only wed Vanessa because he could fit into her clothes. It seemed that every aspiring young actress auditioned for the part but they gave it to platinum blonde bombshell Jayne Mansfield whose career was on the down slope. This didn’t help as her scene was left on the cutting room floor and didn’t make it into the final print. As a sort of consolation for not getting that role, I was hired to appear as one of the decorative background cosmeticians working at the funeral parlor with the film’s leading lady, Anjanette Comer. Little did I know that this would forever change my life.

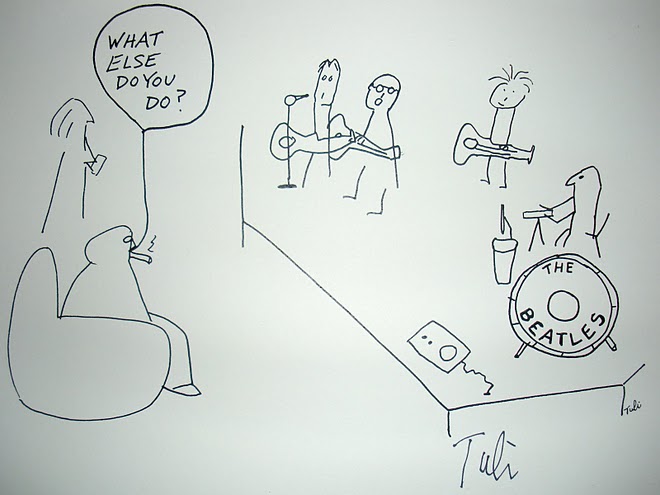

The Loved One starred Robert Morse, who looked adorable with his shaggy Beatles haircut, as the young British poet named Dennis Barlow newly arrived in Hollywood to visit his upper crust uncle (John Gilegud) who shortly thereafter commits suicide when he is unceremoniously fired from the movie studio he has worked at for over thirty years. Barlow then is given the responsibility of the burial arrangements and is led by his uncle’s pompous friend (Robert Morley) to the ornate Whispering Glades funeral parlor foundered by the Blessed Reverned Glenworthy (Jonanthan Winters). He falls in love with one of the cosmeticians named Aimee Thanatogenos (Comer) a strange girl who fantasizes about death and lives in a condemned house on stilts in the Hollywood Hills. But their blossoming romance is complicated by head embalmer Mr. Joyboy (Rod Steiger), a rival for the charms of Miss Thanatogenous and Barlow’s humiliating job at a pet cemetery, which he tries to keep a secret. When all the men in Aimee’s life let her down—Barlow’s occupation is revealed, Joyboy deserts her, Glenworthy proves to be a lecherous phony, and the Guru Brahmin (Lionel Stander), whom she writes to for advice turns out to be a drunkard—she commits suicide by embalming herself.

A number of actors make cameo appearances including James Coburn as a customs inspector, Tab Hunter as a tour guide, Roddy McDowall as a movie studio executive, Liberace as a coffin salesman, and most hilariously Milton Berle and Margaret Leighton as a battling Beverly Hills couple whose dog has died.

My scenes were set at Whispering Glades Funeral Parlor, which took weeks to shoot, and were filmed on location in the extensive gardens and interiors of a lavish estate called Greystone located on Sunset Boulevard. It was the former residence of multimillionaire Edward Laurence Doheny II. I worked mainly with Anjanette Comer, Rod Steiger, and Pamela Curran. Anjanette never spoke to me or any of the other girls playing small roles. Since she had the leading role, I think she thought we were beneath her and not worth her time. She was also busy learning her lines.

I remember hanging around doing nothing my first day on the set. On the second day it seemed it was going to be a repeat of the day before. I was sitting around earning more money than I ever did as a ballet dancer so I really couldn’t complain. There was a whole bunch of us getting paid just to show up. I was all decked out in the same costume as Anjanette, a tight form-fitting white dress with a matching veil, but with absolutely nothing to do but to just sit there and wait in the hot August sun. I spotted a nice shady chair in a quiet spot and made a beeline for it, thinking I could pass the time over there. A crew guy saw my lightning move and said, “That one’s a dancer.” Terry Southern overheard and saw me. He came over and introduced himself as the film’s screenwriter. He was very slim at this time and was wearing his trademark dark sunglasses with a cup of coffee in one hand and his script in the other. I thought, “Oh, great. Another old guy is hitting on me.”

I had recently met the notorious author Henry Miller of Tropic of Cancer fame at an afternoon garden party thrown by a big time producer of MGM musicals who also happened to be Canadian. Once Miller noticed me, he never left my side and insisted we have our picture taken together. I was initially flattered that such a world famous author would pay so much attention to me but then quickly realized that he was just a guy on the make. He persisted that I give him my phone number and address so he could take me out and I hesitantly gave it to him. I was reluctant because he was much older than I was but as with most lecherous guys his age they don’t consider themselves “old.” They just keep trying. When I ignored his phone calls he pursued me by letter all of which I saved.

Terry Southern, at forty years old, was much younger than Miller’s seventy-five. And to be honest I was immediately attracted to Terry—no surprise there as I seemed to have a penchant for older men so I accepted his invitation to go to his office for a drink. I guess I was destined to fall in with a bad crowd. Henry Miller and Terry Southern were chasing me—I never had a chance.

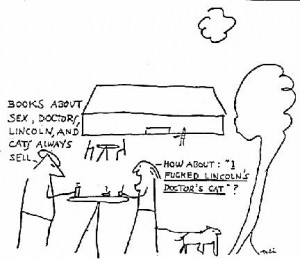

Terry’s makeshift work space was in one of the mansion’s drawing rooms with a full bar. I went, and we talked. He seemed quite taken with me, and asked me a lot of questions about my life. I thought Terry was more interesting than most men I had met for a long time. I had read The Loved One years ago one cold winter in Toronto and found it most enjoyable, and had seen Dr. Strangelove a few months earlier. He said he had a best seller out, and I coolly replied, “I don’t read best sellers.” The next morning he brought a copy of his book Candy for me. I took it home and read it that night. He wrote “I love you” in tiny script on the inside corner of the cover. It seemed a bit hasty.

The next day we went to lunch at the Polo Lounge in the Beverly Hills Hotel where he was staying. I was still in my Canadian version of what to wear, and showed up in a nice straw hat and white crochet gloves. Terry must have thought that was really weird but he kept his comments to himself. I learned that he spent a lot of time in Paris and New York City writing short fiction and nonfiction for such magazines as Paris Review, Harper’s Bazaar, Esquire, and Olympia Review, among others, and that besides Candy he authored the novels Flash and Filigree and The Magic Christian. Oh and he also revealed that he had a wife. Seeing how that didn’t faze me (I was still legally married too), Terry invited me to his hotel room where, when he was not working on The Loved One, he was writing a screenplay for Candy. A lovely woman named Margo, who worked in the costume department on the film, came by after work to “freshen up.” They had obviously known each other for awhile, and had worked on pre-production together. Margo was surprised to find me there. It was a very awkward scene. After she had showered, she said to Terry, “I’m her dresser, I can’t compete with that” and quickly left. Terry said he had planned to work his way through all the beautiful women on the set, but got stuck at me.

I learned from Terry that he just received an Academy Award nomination for co-writing Dr. Strangelove and he became inundated with screenwriting offers. He chose to work with Christopher Isherwood in adapting and updating Evelyn Waugh’s The Loved One because he loved satire, which was evident if you saw Dr. Strangelove. Terry talked very excitedly about his love of collaboration and felt this would be an interesting challenge poking fun at the Southern California funeral industry and Hollywood’s British “colony” of actors.

Terry continued on telling me that after arriving in Hollywood, he booked himself into the Beverly Hills Hotel. Tony Richardson, whom Terry called “Tip Top Tone” as he loved giving nicknames to people he liked, was hired by producer Martin Ransohoff of Filmways to direct The Loved One, which was going to be distributed by MGM. Terry and Isherwood wrote most of the screenplay at Richardson’s home while lounging around the swimming pool. Tony’s then-wife Vanessa Redgrave was also there, and he sent Terry and her to do research at several funeral homes. They pretended to be a couple who just lost a loved one. Redgrave really got into the part, weeping and ringing her hands at every funeral home, while Terry played the stalwart husband. Terry always said how impressed he was with her. After the script was completed, Isherwood returned to London…

After filming was completed on Girl Happy, Sam Armstrong got me an audition at MGM for a movie called The Loved One, which leads back to my meeting Terry that day on the set. Being with Terry, I got to know first hand the machinations of what was going on around me. Prior to that, the only thing that I was conscious of was that actress Pamela Curran, a blonde, statuesque Julie Newmar-type whom I shared a trailer with and worked with on Girl Happy, was popping some kind of pills whenever she got the chance. I never asked for one. It was just so Valley of the Dolls. Some of the other gals who played Whispering Glades Hostesses thought Pamela was haughty but I thought she was just stoned.

Terry explained to me that Tony Richardson had just been awarded an Oscar for directing the ribald British comedy, Tom Jones. However, he had made the deal for The Loved One before his big win, and wanted to re-negotiate his contract. He did not succeed, and was furious, working, in his estimation, for less than his worth. Tony compensated for this by charging the company as much as possible in production costs. The screening of the previous day’s dailies was held in the basement theater of the Beverly Hills Hotel. Everyone had to run a gauntlet of long tables laden with salmon, shrimp, cold cuts, and every type of gourmet treats you could possibly imagine. There was expensive food there for anyone who passed by. Champagne, Dom Perignon, only the best of course, was served at seven thirty in the morning—corks were popping every day like it was New Year’s Eve.

Tony Richardson while filming took as many takes as possible and wasted time between set ups by working at a snails pace. Terry chuckled that Tony had barred the executive producer, Martin Ransohoff (who Terry modeled the producer character in his novel Blue Movie on) from the set. Richardson purposely went over budget and extended the shooting schedule by weeks.

Terry Southern was one of the first writers or maybe the first writer to always be on the set. In those days, you handed in your script and you went home never to be seen again. Terry changed all that for a while. He was constantly on the set at all times to make script changes and co-wrote these wonderful vignettes for all these incredible actors. He loved to tailor his work to a specific person. He would watch what the actor was doing, and then he and the actor would have their heads together in deep conversation. The actors loved his work and his dialog so much that Richardson couldn’t get them to stop. A less confident director probably would not have allowed Terry to talk to his actors.

Terry felt that Richardson’s perverseness reached into his casting choices. Despite the fact that such popular and talented young British actors at the time such as Albert Finney, Terence Stamp, David Hemmings, and Tom Courtenay would all have been wonderful in the lead, Tony stuck with the roster of MGM contract players. He cast as the English poet American actor Robert Morse who prior to this had starred in the hit Broadway musical How to Succeed in Business without Really Trying and the non-hit movie comedies, Honeymoon Hotel and Quick, Before It Melts, which co-starred Anjanette Comer in her film debut. She too was not quite right and a bit bland in the role but she did have a macabre look to her, which I thought was perfect for the part. One day while at lunch, Richardson saw actress Pamela Tiffin dining and remarked that he wished he would have chosen her for the role of Aimee instead of Comer.

Other than the two leads, Terry loved all the other casting choices for the star cameo roles. He was delighted to find himself writing for stars like Jonathan Winters, Rod Steiger, Margaret Leighton, Milton Berle, Sir John Gielgud, and Liberace. The one performer that got away to Terry’s disappointment was the notorious comic Lenny Bruce. Terry wanted him to play the foul-mouthed drunken advice columnist played by Lionel Stander, who managed a whole new career out of the role after being a blacklisted actor due to the McCarthy hearings in the Fifties. Lenny Bruce turned it down, saying that he wanted to make his own movie.

Terry and I visited Lenny Bruce twice in his Hollywood Hills home. The first time it was early evening in the summer of 1964. It was still daylight, and the sun was shining when we arrived at his house, which over looked a steep ravine. Terry knew Lenny from New York; in fact he had been with him at the Russian Tea Room when President Kennedy was shot. Zero Mostel was also in the restaurant, and rushed to the phone to call his stock broker. Lenny had a show that night at a club, and on hearing the horrible news, asked Terry what he should say in his act. Terry didn’t know what to advise him, and when he showed up at the club for the show, Lenny Bruce walked on stage and said, “Phew, poor Vaughn Meader.” Meader was an up-and-coming comic whose whole act was based on his impression of President Kennedy. His career was now over.

I too had met Lenny Bruce before, in Atlantic City. I had flown there from Toronto for a long weekend, with a member of the Toronto demimonde. The plan, not completely told to me, was to meet Frank Sinatra, who would then be smitten with me. It seems a bit of horse trading was going on at my expense. I sat at the end of the bar and Lenny Bruce came on stage. He spotted me immediately and did the whole show to me. He rushed over after his act to introduce himself. Not knowing the plan of my demimonde friend, I thought Lenny Bruce was wonderful. I knew his work—everyone did. I stayed for the second show, and we left together.

He was staying in a rooming house with the smell of cabbage, and babies crying. All his money obviously went for dope. On our way over from the bar, he let me carry a small tartan case. I assume it held his precious drugs. We went up the rickety stairs to his room, which to my relief must have been the best room in the tenement. We lay on the bed while he wrote poems and signed photographs pledging his love to me—nothing sexual happened because it couldn’t. I guess, being a junkie, he didn’t want to get into all that thrashing about, with an embarrassing end. We didn’t even snuggle. We talked and listened to music, and in the morning after giving me a chaste goodbye kiss I got on a plane back to Toronto. Terry wouldn’t have believed that story in a million years, and I certainly never told him. To keep it a secret, I foolishly tore up all the poems and pictures Lenny gave me.

When Terry and I walked into Lenny Bruce’s house Terry introduced Lenny to me. Lenny shook my hand and looked into my eyes and said, “How do you do.” He sensed this was an important relationship for both of us, and that men are jealous creatures. He was so cool and hip. Lenny’s wife Honey Bruce was there. She served drinks, and was charming and gay.

The second time we met with Lenny Bruce was in 1965. Terry and I went with William Claxton who was renowned for his photographs of some of best known jazz musicians in the world. He was a good friend of Terry’s and was hired to be the still photographer on The Loved One. It was afternoon, and Lenny was alone in a wheelchair with both legs in casts up to his thighs. He explained that while under the influence of LSD he had jumped out of a window in San Francisco, hollering ”Super Jew,” breaking both legs. Claxton took pictures of him and Terry around a small pool, with Terry pushing the wheelchair, and saluting his friend.

Lenny was so fascinating that day. He was totally involved in his trial for obscenity. He told us that the prosecutor had to read from his act but he wouldn’t say the offending word—“cocksucker”—which had to be noted in the record. Once the lawyer said it aloud it was set free and everyone in the courtroom wanted to say it.

Of all the actors in The Loved One the standout had to be Rod Steiger who played the effete chief embalmer Mr. Joyboy who falls in love with Anjanette Comer’s bizarrely shallow Aimee Thanatogenos whom he helps promote from cosmetician to the first female embalmer. The pairing of the two is straight out of The Addams Family. His character has to be one of the most memorable and disturbing from Sixties cinema. The scenes with Rod and actress Ayllenne Gibbons as his obese mother are both hysterically funny and painful to watch. Fans today can still recite the ditty Joyboy sang to Ms. Thanatogenos about his fantasy trip to the market for his mother, “Mama’s little Joyboy wants lobster, lobster. Mama’s little Joyboy wants lobster for mom.”

I was so thrilled to be working with Rod Steiger because he was my favorite actor ever since I saw him dance in the ballet sequence from the movie musical, Carousel. He lifted ballerina Bambi Lynn so gracefully and didn’t break her ribs, which is a feat for someone without ballet training. I regret that I never told him how wonderful I thought he was. But then maybe I couldn’t muster up the courage because at lunchtime Rod would come to the set with his dyed blond hair in curlers wearing nothing but a Speedo. He was some sight standing patiently in line with his tray in-hand waiting to get his turn at the lavish buffet spread. Terry and I even paid him a visit at his Malibu beach house. That day he seemed lonely and tired. I still didn’t mention how much I admired him. Sometimes people just get shy and don’t speak up when they should especially if they have something nice to say. I’ve always regretted not telling Rod how much his work meant to me.

Terry’s favorite scene in the movie was the one he created when Joyboy’s mother in a gluttonous rage manages to get her immense body out of bed and raids the icebox gorging on leftovers so voraciously that she falls to the floor with the refrigerator’s contents spilling out on top of her. Terry cherished a still autographed photo Ayllenne Gibbons gave to him.

Shooting of The Loved One finally came to an end and Terry was at a high at this point of his career. Candy was on the best seller list of The New York Times, and Dr. Strangelove was in the theatres. One weekend Terry came to pick me up, and I met John Calley, whom Terry nicknamed “Black Jack,” an elegant young producer on The Loved One who Tony Richardson did allow on the set, and Frank Perry, who had directed the acclaimed film David and Lisa starring Keir Dullea and Janet Margolin as psychologically disturbed teenagers who fall in love in a mental institution. Calley and Perry wanted to make a small art film of Candy. When shooting was completed on The Loved One, Terry didn’t go back to New York and his wife. Instead he chose to remain in LA and he moved into the Chateau Marmont Hotel on Sunset Boulevard.

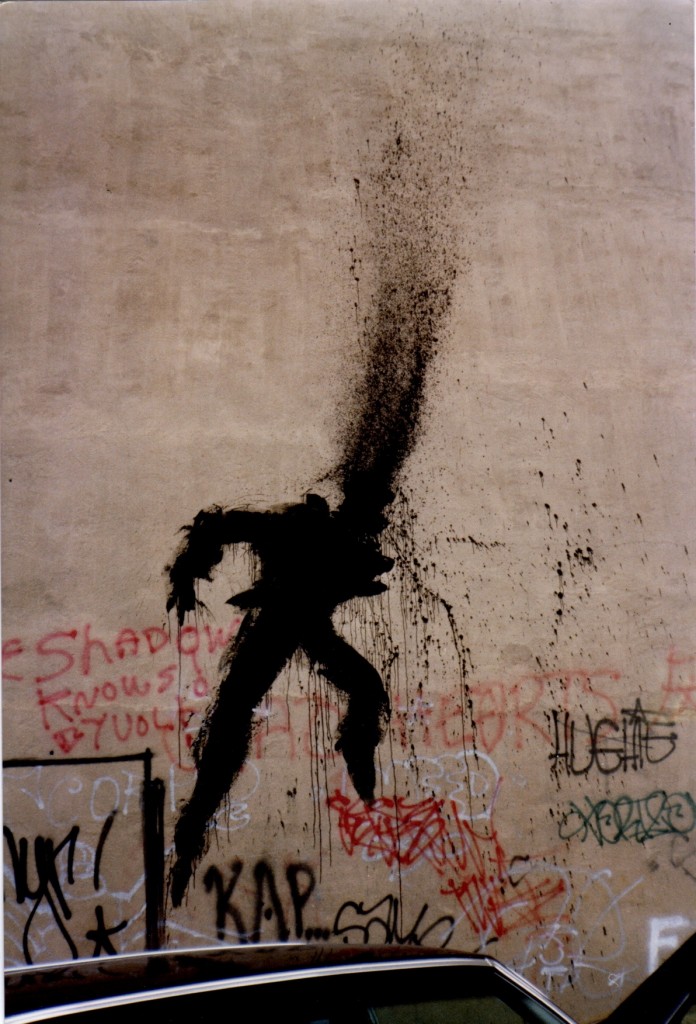

When not working on the Candy screenplay, Terry collaborated with his good friend William Claxton on a picture book entitled The Journal of the Loved One. They did this not for promotional purposes dictated by MGM but just for the fun of it. The book written diary-style features rare behind-the-scenes photos of the making of the movie accompanied by Terry’s witty musings and comments on the proceedings.

Terry and I didn’t attend the opening of The Loved One because we were out of the country. When I finally saw the movie, I was hard pressed to find myself despite the many weeks I worked on it. I’m on screen for a few brief moments thanks to Terry who told Tony Richardson, “The kid needs a break—give her a close up.” The camera zooms in on me as I look on disapprovingly from the adjoining cubicle while Anjanette coyly flirts with Rod Steiger who is examining the make-up job she has performed on someone’s loved one.

The Loved One (with the tagline, “The motion picture with something to offend everyone!”) received mixed reviews when it was released though Terry’s screenplay with Christopher Isherwood garnered praise. Even still, the ahead-of-its-time black comedy was a bit too distasteful for 1965 audiences and coupled with the less-than stellar pairing of Robert Morse and Anjanette Comer in the lead roles couldn’t attract paying customers. MGM also lost faith in the movie and didn’t give it the promotional push it needed to succeed at the box office. But then again a dark satire such as this, which was truly a scathing condemnation of the Sixties, was not what the studios were used to marketing in the days of The Sound of Music and Mary Poppins.

As for Terry, he was disappointed in the lack of enthusiasm for the movie but he just loved the scenes that he wrote (he always did). He felt strongly that cinematographer Haskell Wexler deserved at least an Academy Award nomination for his stunning black-and-white cinematography and that Tony Richardson did a good job with the movie other than with the casting of Morse and Comer, whom Terry was displeased with. Years later, Robert Morse revealed that since he had such a hard time maintaining a British accent, Tony had audio taped him while reciting his entire dialog from the script and it was looped into the film during post-production.

Today, fans and historians consider The Loved One to be one of the most underrated comedies of the Sixties. Terry would hardily agree as he always felt that this was his most under appreciated work. After years of clamoring for it to be put out on DVD, MGM finally relented and released it in 2006 to many a film aficionados’ delight.

©Gail Gerber and Tom Lisanti