FAMOUS LONG AGO REDUX:

Raymond Mungo’s

SILK ROAD MAHABHARATA #4

Raymond Mungo’s

SILK ROAD MAHABHARATA #4

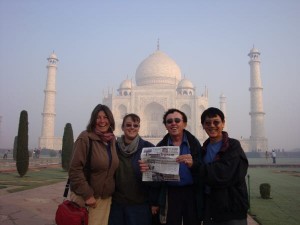

Ellen Berger, Alicia Doddy, Ray Mungo and Robear Yamaguchi

Ellen Berger, Alicia Doddy, Ray Mungo and Robear Yamaguchi

The airport in Phnom Penh was tiny and breezily open to the morning weather, in the 90’s. Landing there felt like arriving on Maui. We purchased tourist visas for $20 each (US cash only accepted) and were deposited into a one-room receiving area which served as baggage claim area and duty free shop. I bought a quart of Stolichnaya vodka for $13 (cheap!) as a gift to our host Barry, whom Ginnie told us was fond of the stuff. We also brought with us a pound of See’s chocolates, famous brand in southern California, as a house gift.

Barry and Todd greeted us warmly just outside the departure gate, dressed in short sleeves, tattered jeans, sandals without socks, looking more like tourists relaxing on a winter vacation than we did. And they promptly produced a couple of tuk tuks, the ubiquitous motorized rickshaws on which much of Asia rides to market or work. Barry, Todd, Helen and I climbed into the first of these open air chariots, with the younger people – Hub and Ginnie – following behind us in the second one, and we rattled into the crush of mad traffic with engines roaring and belching great clouds of noxious fumes. Todd, grinning, told us he’d already seen two nasty vehicle collisions that day. (Note to self: keep arms and legs inside the cab.) Heedless of all rules and caution, the tuk tuks careened into a swollen river of mopeds, scooters, bicycles, taxis, trucks, buses, and pedestrians all flailing willy-nilly in every direction, swerving around each other in surge of death-defying chaos.

First impressions: Cambodia is one of the poorest countries of the world. Malaria and polio are both rampant and uncontrolled. Child prostitution is famously common. And even if you don’t get run over in the insane traffic, the air pollution alone may do you in. Emphysema sufferers, keep out. Phnom Penh in 2008 reminded me of Bangkok in 1972; and while you can still find wrenching poverty in its slums, Bangkok now has gleaming skyscrapers, a modern elevated Sky Train, and a prosperous tourist trade. Phnom Penh has only the earliest stages of such development, but Barry warned us not to talk about Thailand, especially not by comparison, in Cambodia. There was a tense military standoff going on at a contested border region between the two countries, he said, and a general resentment among Cambodians toward their richer Thai neighbors.

We struggled to hear our hosts over the incredible din of the traffic. They seemed to be saying that we were not, in fact, headed to their house. Not? No, every bedroom was now filled with Barry’s students. But, Todd shouted through the racket, we were going to a hotel, the Her Royal Highness, which had been carefully selected for us by one of Barry’s acolytes, and where two rooms had been secured for us – already prepaid. We would be more comfortable there and have the advantage of private baths, we were told, and our hosts had planned our day and would provide all the transportation and meals. Helen and I agreed we felt like recipients of truly “royal highness” hospitality, while Ginnie and Hub, riding in the second tuk tuk, were ignorant of our new plan and destination. They were startled when the drivers pulled up not in front of Barry’s “five bedroom mansion,” but on a dusty street crammed with open air businesses in front of the imposing hotel with rooms advertised at $15 a night.

The lobby of Her Royal Highness, open to the heat and glare outdoors, had been “recently remodeled” in faux grandeur. We had cold beers from the bar while waiting for our rooms to be made up. The place also served meals, everything very cheap and all prices cited in US dollars. Barry was right, Cambodia has its own currency (the riel) but nobody, least of all the Cambodians, wants to accept it. Oh, the irony – just a week earlier, the increasingly dire condition of the US economy had led Hub’s “bearish” brother in Arizona, who closed all his bank accounts to invest in gold, to warn us that our dollar might prove useless in Asia if it collapsed before Christmas. He advised us to cancel the trip. But we found the hundred one-dollar bills we’d brought along for tips and small purchases were eagerly snatched up by grateful Cambodians harboring no disdain or qualms about good old George Washington with the funny hair.

Barry and Todd laid out our schedule for the day. Visit the National Museum, lunch at the foreign correspondent’s press club, tour of Barry’s school and his famous five bedroom house, drinks at the elegant Elephant Bar inside the posh Raffles hotel, dinner at a genuine Khmer cuisine restaurant. It was an ambitious program for travelers coming off a grueling 24-plus hour long plane trip, groggy with jet lagged fatigue, plus Ginnie announced she was coming down with some kind of a cold. Uh oh.

But we all consented to the popular wisdom that you should get on the clock at your destination as soon as possible. Don’t indulge your jet lag by, say, going to bed at noon merely because it happens to be midnight on your body clock and you’ve already lost one night’s sleep and are exhausted. No. Get with the program at local time, work, play, move around, eat and sleep at normal hours in your new vicinity, and make the adjustment as quickly as possible. We agreed to the day’s agenda and pleaded for an hour in which to get settled in our rooms, shower and change out of our airplane clothes into cleaner, lighter gear.

The rooms were third floor walkups and the gaudy lobby gave way to plain walls and darkened corridors. Her Royal Highness was a backpacker’s hotel, lacking many amenities but providing the basics – severe looking twin beds and a shower that drained through the floor. Barry moved a small throw rug from a nearby unoccupied room to protect us from slipping on the oilcloth.

When our group of six reconvened in Her Royal lobby an hour later, Ginnie’s cold symptoms had morphed into a flu onset – blocked sinuses, sneezing, coughing, achy. We pooled our medical resources and came up with a miscellany of over the counter and prescription remedies, both Western and homeopathic. She popped some pills and gamely carried on. The rest of the day played out in a semi-comatose jet lag haze, like living inside a bubble or observing life from behind a veil.

The National Museum was a work in progress, with construction crews laboring alongside the sculptures. Helen, knowledgeable about such things, pointed out that the Louvre in Paris houses finer and greater Cambodian Khmer art. The French colonized Cambodia and essentially looted the most precious artifacts. The foreign correspondent’s club was a breezy second story affair overlooking the Mekong river, where Barry and Todd bought us lunch and drinks amid a buzzing crowd of tourists—most, I assumed, were not in fact foreign correspondents as the place was not a private club, anyone could enter, but the menu was downright American (pizza and French fries with that), the ambiance rakishly international.

Barry’s school, a Buddhist institution, proudly announced at its entrance gate “classes taught by American pofessor (sic)” and seemed quaintly primitive. Some of the computers in the student lab were junkyard quality by our standards, but any computer at all is a luxury to students who come to Phnom Penh from impoverished villages in the countryside seeking a modern education as a step up in life. These students greeted their “pofessor” with genuine warmth at the gate. Some of them also occupied those five bedrooms in Barry’s famous house.

The afternoon was latening and our strength ebbing when we finally arrived at the storied home. It hid behind heavy gates on a nondescript street of rusty auto repair shops, small open air businesses and unprosperous looking shanties. Unemployed men loitered in the dusty gutters, skinny dogs slued through alleys. Barry unlocked the massive front door and escorted us into a kind of stone foyer, where we all had to take off our shoes before entering the living quarters. It felt like entering a Buddhist temple, and, as it turned out, Barry was an aspirant to the faith.

In the kitchen, several young men sat at a small table while a young woman worked over the stove. “Papa”’s extended family. At age 70 Barry had taken his teacher’s pension, left his comfortable condo in LA and rented for $300 a month this three story house where he attempted to practice right thinking while adopting and assisting a coterie of needy Cambodian youths. Most striking was a boy of about 18 who was deaf and communicated in sign language. “He’s very angry at the entire world,” Barry said. Indeed, he glowered.

Evening chants murmured through the stone walls. We drank a bottle of red wine and listened. I was suddenly glad – grateful, I guess – not to be spending the night there. I’m an atheist, uncomfortable in church. The power failed and we understood why Barry had told us to bring personal flashlights. It was time to travel on to the happy hour (drinks half price) at the famous Elephant Bar inside the grand Royal hotel, a Raffles property. We pleaded exhaustion and Todd said, don’t worry – a few drinks, a quick bite at the Khmer authentic restaurant, and we’d be finished by eight o’clock, guaranteed.

After a spate of confusion – the tuk tuk drivers misunderstood Barry’s instructions and initially delivered us back to the Her (our) Royal Highness hotel instead of the five star Royal – we wound up in the posh Elephant Bar sipping martinis while idly watching some British boys shoot pool. The clientele was entirely Caucasian, the service staff all Cambodian, the martinis graced with two plump olives each. We took refuge from the grinding poverty of the streets inside the walls of a private palace.

Helen graciously paid the bar tab, as our hosts had been paying for everything all day and we wanted to contribute. Hub and I offered to pick up the check at the Khmer restaurant, where we dined on amok, a tuna delicacy, and other equally tasty local specialties, and came to realize that Cambodian food deserves its good reputation. (Cambodians are said to insist on the freshest ingredients.) Equally delectable was the check, which came to about $55 for dinner for six people, including wine. No credit cards, US cash only. I vowed to eat amok every day in Cambodia. I wanted to be amok. “You are what you eat,” as we used to say back in the day.

We didn’t finish by 8 p.m., of course, but when sleep overcame us at Her Royal Highness, it brought down a heavy, dark curtain that would lift only when the chants of invisible monks announced the dawn. It was the longest night of the year – the winter solstice.