FAMOUS LONG AGO REDUX:

Raymond Mungo’s

SILK ROAD MAHABHARATA #6

Raymond Mungo’s

SILK ROAD MAHABHARATA #6

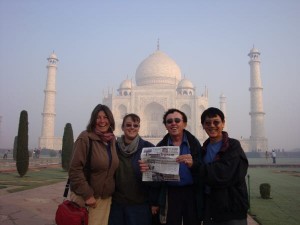

Ellen Berger, Alicia Doddy, Ray Mungo and Robear Yamaguchi

Ellen Berger, Alicia Doddy, Ray Mungo and Robear Yamaguchi

[ 6 ]

Come the rosy dawn, actually an hour before daybreak, Poan returned to the Golden Banana to ferry us to the principal Angkor Wat to watch the sun rise over its majestic spires. The dawn ritual is de rigueur for visitors in Siem Reap, like climbing the Eiffel Tower in Paris or visiting the Taj Mahal under a full moon.

But the longest night of the year was moonless in 2008 and we had to walk from the parking lot to the Wat along rutted, stony dirt trails in inky darkness. Once again, our individual flashlights saved the day as Poan, oblivious to the dense blackness, charged ahead of us. More than once, we nearly tripped or fell down and I was thinking, “This better be good” or “What the hell are we doing?” but damn it,there really was an electric thrill in the air and I was still high on the memory of my excursion to the Other Side of death, not to mention the whiff of ganja, and loudly singing “Auld Lang Syne” on this first day after the solstice, this true New Year’s morning. Should auld acquaintance be forgot and never brought to mind? Indeed.

If Hub and the gals were a bit annoyed with my constant babbling about the groovy trip to outer space, they were kind enough to take my story at face value. Helen was perhaps most skeptical, I sensed, she’s a Pisces like myself and knows how the slippery fish is prone to flights of imagination, not to mention fond of every possible consciousness-altering substance. I once talked her into getting her own medical marijuana prescription on some flimsy premise. But she’s also an historian, a scholar of facts, and more planted on solid ground than I am.

Poan led us to a clearing in view of a lake beyond which the stately Angkor Wat reposed in ghostly silhouette against the blue-black sky on the eastern horizon. A sizable crowd was gathered, waiting for the mystical moment when the sun would rise behind the Wat and bring in the new year. Poan deposited us in the tourist throng and wordlessly retreated to a knot of other tour guides, postcard vendors and child merchants clustered in the rear and then, as you’d expect, the sun did rise exquisitely slowly and the Wat did shine. It was a lovely spectacle punctuated by the popping of a thousand camera flashes, but nowhere near as sublime as Heaven.

On the trek back to Poan’s car, Hub made the tactical error of buying a pack of postcards from a little girl of eight or nine, which set off a feeding frenzy of other child vendors hawking Angkor Wat picture books, key chains, t-shirts, and other kitschy souvenirs. We were quickly surrounded by this juvenile mob which chased us all the way to the car and then pounded on the windows once we had safely squeezed into the vehicle. “You should not give money to children,” Poan sternly lectured. “It only encourages them in their begging. They should be in school.” He inched the car forward through the press of shrieking urchins.

“Looks like you incited a riot,” I teased my husband. “Well, I did get 12 postcards for a dollar,” he protested.

Poan dropped us off at the Golden Banana so we could have breakfast and showers, handing us a printed itinerary of all the sights planned for our next two days – a full schedule of touring various wats, concluding on the last day with a boat trip to an indigenous Cambodian village of river dwellers. We pored over this ambitious plan while eating a delicious breakfast, included in the daily rate. The more we stayed in the GB the better it got. Advertised as gay-friendly, the place lived up to its boast. It even had stacks of glossy gay and lesbian magazines by the pool. More than gay-friendly, it was gay-amorous. The kitchen boy who came to our table to enquire how we liked his food was also an apprentice cook at the fancy restaurant in town, the only one that took American Express. The bartender boy supplied cold Australian chardonnay and wicked weed with a smile. The beds were comfy, the rooms well appointed. Ginnie continued to suffer flu symptoms, and needed to lie down at intervals. We strolled the garden, splashed in the pool waterfall, engaged in light banter with the other guests – a pan-global backpacking crowd – and swapped paperbacks in the lobby library. While the rooms lacked TV or phones, we craved neither. The hotel was so accommodating it was difficult to leave.

Studying Poan’s itinerary at the breakfast table, bold Helen raised the taboo question: did we absolutely have to do all these planned excursions? Shouldn’t we have the right to choose where we want to go and decline other places, or just rest at the Golden Banana, or stroll the village streets independently? Of course we should. That’s an American attitude toward travel. From that consideration rose the radical conclusion that we’d prefer to take the river boat trip first rather than last, wanted to be taken to a big supermarket (rumored to exist) to stock up on wine and snacks, and didn’t actually care whether we returned to the Angkor Wat that day at all. We saw it at dawn already.

In Asia, however, all personal and business relationships revolve around “face,” so our challenge was to find a way to drastically alter Poan’s itinerary while allowing him to save his dignity, his face. The plan as hatched was to tell him we loved his itinerary, compliment him on his choices of destinations, explain that we would like only to change the order of events – that is, to move the boat trip from last to first – and at some later time we figured we could blame Ginnie’s flu for our having to rest at the hotel rather than climb over crumbling temple ruins all day. It was devious and baldly disingenuous but we’d also assure Poan that we would distribute his business cards among our legion of Long Beach friends (entirely fictitious) who were interested in visiting Cambodia and would need, as surely as we did, an excellent tour guide such as himself. Whew.

When we delivered this spiel to Poan, he seemed a bit confused, even stunned. People who hired him as a guide to the Angkor Wat generally wanted to maximize their time at the Angkor Wat, but we preferred to take a boat ride, how peculiar. But he conceded the point with a smile and we all got into the chauffeured van and took off for the river docks, where tour buses full of Chinese and Korean tourists disgorged their passengers onto pleasure cruise craft. Poan quickly made arrangements with a canopied motorboat and two man crew and we left our van and driver in a rubbish-strewn dirt lot by the riverbank and pushed off into murky waters alive with “dragons” – small crocodiles – and foaming algae.

Our funky ship of fools, with seating for about a dozen people, growled and ground its way upstream, belching purple exhaust, as we snapped photos and shot home video. It didn’t feel safe, exactly, especially when larger boats left us in their wake, but the river was fairly narrow and we were never beyond swimming distance to the shore. (Not that we’d care to share the water with “dragons” and bacteria.) The landscape was less than beautiful – hardscrabble rice paddies, occasional thatched-roof huts, people fishing from the banks. But it was a lovely day for a boat trip, a Cambodian idyll.

After an hour’s journey, we arrived at the River People village, which was not idyllic in the least. Folks were encamped in squalid temporary housing clustered on one side of the river and living aboard primitive boats and raft-like platforms. Every six months the water level shifted and the entire community had to uproot itself and move to the other side of the stream. Skinny children and toothless elders regarded us with blank stares. Even skinnier livestock languished prone under the mid-morning sun. This was a different vision of Cambodia than the relatively more prosperous capital of Phnom Penh and tourist Mecca of Siem Reap. This was the impoverished countryside from which a lucky few would migrate to the cities. Young men, for example, seemed to be scarce. This was a world of hungry children, laboring mothers, feeble old people, lack of basic services like electricity and plumbing, and absence of education and opportunity. Yet the village was ancient. The River People have been there as long as history can remember. We glided through it slowly as if in a floating market, but nothing was offered for sale.

Our animated chatter was reduced to silence. It didn’t seem right to take photos – that seemed like an invasion of the villagers’ privacy, such as it was. We’d been forewarned to expect scenes of grim poverty but the reality proved worse than the imagination had conjured. Our ship turned around and headed back.

Halfway through the return trip, the boat pulled up to an island evidently constructed for tourist traffic. (It might have been man-made.) It had a restaurant, primitive bar (beer only) and a cheesy souvenir shop purveying straw hats, t-shirts, costume jewelry, sunglasses, and colorful “native” looking clothing. Real Cambodians don’t wear such silk finery except on traditional occasions. We hadn’t been advised that we’d be taken to this sadly tacky emporium, but Poan acted as if it was simply part of the trip and from the way the boat captain followed us around the place I got the feeling he would benefit by a percentage cut of any money we spent, which in the event was practically nothing. I had no objection to buying souvenirs but couldn’t find anything I actually wanted. Ginnie, flush with fever and high on a combination of many cold and flu remedies, acquired a few trinkets, and we sailed on.

By the time we arrived back at the dirt road dock in Siem Reap, it was past noon. We asked to be taken to the supermarket and, after mistakenly driving us to the old town market, Poan got us to the one Western style large grocery in town, indistinguishable from any Safeway or Kroger’s you know. It had a vast selection of wines and packaged goods as well as OTC drugs (Valium and Xanax, Viagara and Vicodin, etc., for sale, cheap, without prescription – yes, we loaded up) – stationary supplies and other useful sundries. Poan and the van driver were bug-eyed at the sight of us emerging from this emporium lugging plastic bags stuffed with merchandise, after we’d basically refused to spend money at the riverboat tourist souvenir shop. Then it was back to the Golden Banana for lunch.

As Poan started laying out our afternoon itinerary, the face-saving strategy swung into action. “After that wonderful sunrise at the Wat and great boat trip to the River People village and huge shopping excursion, we’re exhausted. Poor Ginnie is obviously very sick. We think we’d better call it a day and just rest up at the hotel for the remainder, then we can go back to the Wat in the morning,” I said – words to that effect, sugar coated with compliments. Having no real choice in the matter, Poan agreed, but it was obvious he was puzzled. Why indeed had these four wine-guzzling, pill-popping, pot-smoking stoners from California engaged a professional Angkor Wat guide if they didn’t want to tour the Angkor Wat past one o’clock in the afternoon? He gave us his cell phone number and said he would remain available to us all day and evening if we changed our minds – just call. And with that he was off and we were back in the Golden Banana restaurant gorging on more amok, toasting glasses of wine, conducting English language conversation classes with the GB boys, laughing hysterically and happy to be alive, back from the brink.

The rest of the day slipped by in a cloud of smoke interspersed with siestas, pool time and strolls through the village. Ginnie literally had to go to bed – her flu symptoms had never abated and she was a walking pharmacopeia of powerful analgesics – while Hub and I did so for the pure pleasure of it. Our bungalow was a sanctuary of peaceful comfort from the tumult of travel, a vacation from the vacation. But we did go to dinner at the American Express restaurant where the GB chef was a student apprentice – his hotel food was better and cheaper – and found another pharmacy peddling Vitamin V’s, yum. Brand-name pharmaceuticals like Pfizer and Roche, made in France, for the price of generic aspirin. After three days in Cambodia all memory of the States and the Greater Depression of ’08 had vanished like our youth.

To be continued…

Silk Road Mahabharata #1 at http://smokesignalsmag.com/7/?p=40

Silk Road Mahabharata #2 at http://smokesignalsmag.com/7/?p=1330

Silk Road Mahabharata #3 at http://smokesignalsmag.com/7/?p=2075

Silk Road Mahabharata #4 at http://smokesignalsmag.com/7/?p=2279

Silk Road Mahabharata #5 at http://smokesignalsmag.com/7/?p=2548

| Raymond Mungo is the author, co-author, or editor of more than a dozen books. . In his spent youth, he once ran for Governor of the state of Washington on his American Express Card, before that he attended Boston University, and served as editor-in-chief of the Boston University News in 1966-67; where he spearheaded draft card burnings and demonstrations against the Vietnam War, and in 1967 co-founded the Liberation News Service (LNS), an alternative news source that split off from College Press Service (CPS) and was the forerunner of not only the underground press circuit but alternative weeklies all over America, courtesy of his classic, Famous Long Ago: My Life and Hard Times with the Liberation News Service. Both the original Food Editor and first Sports Editor of Smoke Signals back in the early 1980s, Mungo’s back with us again, almost 30-years later, as quick witted and nimble as ever, but of course in a totally different incarnation. |

OCCUPY BERKELEY

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/20/opinion/sunday/at-occupy-berkeley-beat-poets-has-new-meaning.html?_r=1

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4GsLfNnGs0Y&feature=related

JIM DICKINSON ON PRODUCING

http://www.austinchronicle.com/screens/2011-08-26/moving-pictures/

FILMMAKERS PAY TRIBUTE TO “SLACKER” AND A CITY IN TRANSITION

http://www.laweekly.com/slideshow/the-best-of-burning-man-33985130/

THE BEST OF BURNING MAN

http://www.believermag.com/issues/200603/?read=interview_ramis

INTERVIEW WITH HAROLD RAMIS

http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/features/2011/09/private-eye-201109

The Accidental Institution: This fall, Private Eye marks its 50th anniversary

http://nymag.com/guides/fallpreview/2011/theater/samuel-l-jackson/

Samuel L. Jackson plays Martin Luther King Jr. on Broadway.

*******************************