Mark Jacobson’s

The Splitting Image of Pot

The Splitting Image of Pot

On the one hand, marijuana is practically legal—more mainstream, accessorized, and taken for granted than ever before. On the other, kids are getting busted in the city in record numbers. Guess which kids.

Any righteous cannabisalista knows the timeline, the grand saga of humanity’s interface with the vegetable mind of the planet. Back in 8000 B.C., before Genesis in Sarah Palin’s book, the sentient were weaving hemp plant into loincloths. The Chinese had it in their pharmacopoeia by 2700 B.C. The Founding Fathers used pot processed into paper stock to write a draft of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, which made sense, since Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, along with their slaves, of course, had been raising the crop for decades. There are other, darker dates, too, like June 14, 1937, when Congress, four years after repealing alcohol prohibition, passed the “Marihuana Tax Act,” which essentially outlawed the use of “all parts of the plant Cannabis sativa L.,” including the “growing,” “the seeds thereof,” and “the resin extracted from any part of such plant.”

As far as yours truly is concerned, however, the most important date in pot history took place on a chilly early-December night shortly after the Great Blackout of 1965, when, seated on the pitcher’s mound of a frost-covered baseball diamond in Alley Pond Park, Queens, I first got high on the stuff. That means I’ve been a pothead for going on 44 years now, or approximately 72.1 percent of my current life. Should I live to be 100, that percentage will increase to 83 percent, since, as Fats Waller implied when he sang “If You’re a Viper,” you’re always a viper.

I mention this so you know where I’m coming from, but even if I once knew a guy who claimed to have been the dealer to several members of the Knickerbocker championship teams, I make no claim to being a weed savant. For me, grass is simply the right tool for the job, a semi-reliable skeleton key to the such-as-it-is creative, an enabler of brainwork. Outside of continuing to smoke it, sometimes every day, sometimes not for months, or years, I pretty much stopped thinking about marijuana as a cosmologic/shamanic/political entity around 1980, that insufficiently repressed beginning of the somnambulant Reagan time tunnel, when grass came with seeds and stems and zombies still skulked Washington Square Park reciting their “loose joints” mantra: “Smoke, smoke … try before buy, never die … smoke, smoke … ”

Back then, despite the occasional shouting in the street and polite libertarian proselytizing by William F. Buckley on Firing Line, there was not much thought that pot would ever be legal. Illegality was key to its ethos, central to the outlaw romance. All over the U.S. of A., people were tanking up, driving drunk, killing themselves and others, and still those hot Coors girls were on the TV selling beer at halftime. The whole country was strung out on Prozac. But get caught smoking a joint while reading a Thomas Merton book in the park and it was the Big House for you. What could be more emblematic of the rapaciousness of the culture? That’s how it was until … maybe now.

Could it be that, at long last, the Great Pot Moment is upon us?

The planets are aligning. First and foremost is the recession; there’s nothing like a little cash-flow problem to make societies reconsider supposed core values. The balance sheet couldn’t be clearer. We have the so-called War on Drugs, the yawning money pit that used to send its mirror-shade warriors to far-flung corners of the globe, like the Golden Triangle of Burma and the Colombian Amazon, where they’d confront evil kingpins. Now, after 40 years, the front lines have moved to the streets of Juárez, where stray bullets can easily pick off old ladies in the Wal-Mart parking in El Paso, Texas, even as Mexico itself has decriminalized pot possession as well as a devil’s medicine cabinet of other drugs. At the current $40 billion per annum, even General Westmoreland would have trouble calling this progress.

Compare that with the phantasmagoria currently going on in California, where the legal medical-marijuana dispensaries ask only a driver’s license and a medical letter attesting to some vague ailment—insomnia will do—to begin running a tab at a state-sanctioned, 31-flavor dispensary. Somehow, even with many medical-marijuana outfits advertising “validated parking” and “happy-hour specials,” Western civilization as we know it has not tumbled into the sea. In November 2010, initiatives are expected to be on the California ballot to “tax and regulate” (i.e., legalize) marijuana altogether. Taxing the state’s estimated annual 8.6 million–pound, $14 billion pot crop (more than any amber wave of grain, high-fructose corn syrup included) could bring as much as $3 billion to $4 billion in revenue, enough to buy a couple of B-2 bombers or, failing that, keep a few libraries open an hour more a day.

Pot hasn’t been the preserve of the Birkenstock wearer for years. At least the last three American presidents have been tokers, and you know Bush inhaled, for all the good it did the rest of us. Obama will no doubt tread lightly with the health-care loonies on his neck, not to mention the conservative black clergy he doesn’t want to alienate, but he’s already presided over curtailing federal busts of medical-marijuana dealers who are in compliance with state laws. A lively blogosphere debate ensued over whether Obama could really afford to expend any of his political capital on a bud-in-every-bong policy, as the legalize-it forces were hoping. But the move confirmed officially what many had long known. Pot smoking simply does not carry the stigma it once did, even in the straightest society.

As it turns out, not all those bong-using college students gave up the stuff when they graduated. The other day, I was scanning Andrew Sullivan’s blog, reading posts from salarymen, think-tankers, and Big Board watchers, baring their souls over their continued pot use, long after they were supposed to have put aside such childish things and switched to single-malt scotch. The drug of the counterculture now belongs to a hitherto unglimpsed silent majority, one that knows how to get things done, even legislatively.

The real engine of this is the pot itself. In the old days, there were two basic varieties of grass, the shit that got you fucked up and the shit that didn’t. But now, as is known to any stoner not still searching the skies for that last DC-3 full of Panama Red, pot has been gourmandized. You got your indicas, your sativas, your indoor-grown, outdoor-grown, your feminized, your Kushes, your Hazes, with a new, horticulturally hot number rolling down the gene-spliced pike every day. Historically speaking, a good deal of this flowering comes courtesy of our friendly drug warriors over at the DEA, whose G-man interdiction/kill-at-the-source policy did much to wipe out (anyone remember Jimmy Carter’s paraquat crop-dusters?) international shipments, thereby mobilizing ex-Berkeley botany majors and other supposedly lazy Mendocino/Humboldt County hippies to grow their own.

Beyond this is a budding secondary market. With upmarket pot prices holding at $60 to $70 for an eighth of an ounce, what high-end toker can be satisfied with an intake system based on a 75-cent pack of Zig-Zag when, for a mere $600, you can have a sleekly designed ashless Volcano “vaporizer” to place next to the Bialetti cappuccino-maker? For those about to be drug-tested, there is the Whizzinator, a strap-on extra prick containing “clean” body-temperature piss that you deftly whip out any time your employer/coach/drug counselor hands you a plastic cup. All of this is available in the Internet’s seemingly infinite gray market, where grass-centric URLs offer capsule commentary on the myriad pot strains, including breeding-lineage descriptions right out of the Racing Form (e.g., “Blueberry strain—blue haze X Aussie Duck, from Azura and award-winning Jack Herrer”), date and place of incept, maturation times, buzz properties, etc.

On a recent sweltering afternoon, in lieu of downloading a few seasons of Weeds, I made my way to a top-secret mid-Manhattan location for a little remedial “tasting” administered by the esteemed senior cultivation editor of High Times magazine, known by the nom de guerre Danny Danko. Along with a mini-minyan of like-minded devotees, we hovered over a small but mighty collection of strains: the Chem Dog, the Purps (so named for its red-blue neonish hue), and an assortment of Kush (OG and Bubba) from medical-marijuana dispensaries in Los Angeles and the city by the Bay now referred to as Oaksterdam.

While preparing the samples, Danny Danko, 37, a self-confessed “pot nerd” with a seemingly bottomless capacity for THC ingestion, explained his ethic. A green thumb is not enough to assure the creation of meaningful marijuana, Danko said. “Just because you can grow a tomato that might win a prize at the 4-H club, or a summer squash that’ll knock the socks off the Iron Chef, doesn’t mean you can grow good weed. Give two growers the same seeds and the same conditions, and you can get two completely different qualities of pot. There’s nutrients and care, but there’s an intuitive factor, too—a deep understanding of the physical, mental, and spiritual benefits of cannabis. This isn’t a geranium, it is an art, an act of alchemy.”

We started out on the Purps but soon hit the harder stuff. With the lexicon of winespeak now lapping over into pot punditry, kindgreenbuds.com describes the Purps as possessing “hints of buttery caramel coffee and woodsy floral pine.” Couldn’t say I understood all that from a couple of hits, but the Purps, a spicy little thing, did provide a gleeful cheap amusement-park high not unlike chubby Orson Welles’s tumbling down the fun-house chute in The Lady From Shanghai.

This playland was soon bulldozed by the Kush. An ancient indica strain supposedly dating back to the Hindu Kush, where the stubby plant is used mostly to make hashish, the Kush in its multi-variegations has long been the rage among suburban and ghetto youth who gravitate toward the strain’s stinky olfactory properties and Romilar-esque “couch-lock” stone.

It was here that I learned something about pot, then and now. Prime in the canon of present-day prohibitionists is the claim that today’s pot is so much stronger that it bears no relation to the stuff nostalgic baby-boom parents might have smoked. The message: Forget your personal experience, the devil weed currently being peddled to your children is a study-habit-destroying beast of a wholly other stripe. No doubt, there is merit to this argument (after decades of some of the most obsessive R&D on the planet, you wouldn’t think the pot would be weaker), but I couldn’t fully buy it. This was because the fancy weed I was smoking, and paying twenty times as much for, wasn’t getting me more smashed, at least not in the way I wanted to be.

“I hear this a lot, because back then, you were probably smoking sativas imported from Jamaica, Vietnam, and Mexico,” Danko informed me. Sativas imparted “a head high,” as opposed to the largely “body high” of indicas. The problem with this, he went on, was that tropical sativas, being a large (some as high as fourteen feet!) and difficult plant to grow (the Kush has bigger yields and a shorter flowering time), especially under surreptitious conditions, were rare in today’s market. My lament was a common one among older heads, Danko said, adding that “the good sativa is the grail of the modern smoker.”

Luckily, following the various Kushes, I was able to cleanse the mind-body palate with the mighty Chem Dog, a notable indica-sativa hybrid, reputedly first grown by a lapsed military man—the Chemdog—who came into the possession of a number of seeds following a 1991 Grateful Dead concert.

It was after some moments of communing with this puissant plant life that I was in the proper state to confront the conundrum of the day, i.e., “The Existential State of Weed in Its Various Manifestations in the Five-Borough Area of New York City, circa 2009.”

Race has always been the driving wheel of reefer madness.

And what a woolly hairball of contradiction it is!

There is all of the above, the whole Mendelian cornucopia of the New Pot with its dizzying array of botanical choice and intake gizmos. Yet the cold, hard fact is, New York City, which first banned pot in 1914 under the Board of Health “Sanitary Code” (the Times story of the day described cannabis as having “practically the same effect as morphine and cocaine”), has always been a backwater when it comes to reefer.

The Big Apple viper may gain some small comfort from the fact that getting stoned in California usually leads to being surrounded by stoned Californians, but this does little to mitigate the envy. Here, in the alleged intellectual capital of the world, where we have no medical marijuana (even borderline-red states like Nevada and Colorado do), at the end of the day, you know you’re going to be calling that same old delivery service that comes an hour late and won’t do walk-ups above the third floor.

In this day and age, nearly 30 years after the AMA began flirting with decriminalizing marijuana, you might think New York City marijuana-possession arrests would be in deep decline. You might even figure that Charlie Rangel, the four-decade congressman from Harlem and longtime leader of the Select Committee on Narcotics, had his finger on the pulse when he told a House subcommittee that “I don’t remember the last time anyone was arrested in the city of New York for marijuana.”

Uh … wrong!

The fact is, New York City is the marijuana-arrest capital of the country and maybe the world. Since 1997, according to statistics complied by the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services, 430,000 people age 16 and older have been pinched in the city for possession of marijuana, often for quantities as little as a joint, a reign of “broken window” terror-policing that kicked off in the nasty Giuliani years and has only escalated under Bloomberg and Ray Kelly. More than 40,000 were busted last year, and at least another 40,000, or more than the entire population of Elmira, will be busted this year. Somehow, it comes as no shell-shocker that, again according to the state figures, more than 80 percent of those arrested on pot charges are either black or Hispanic.

From the days of Harry Anslinger—who, as the more or less permanent head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (J. Edgar Hoover–like, he served for 32 years, appointed by the Hoover, FDR, Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy administrations), raved about how most pot smokers were “Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos, and entertainers” whose “Satanic music, jazz and swing” was driving white women into a sexual frenzy—race has always been the driving wheel of reefer madness. It was no fun to find this dynamic still at work in the beloved hometown.

But there they were, down in night court at 100 Centre Street, one marijuana arrestee of color after another, standing before the judge to have their class-B misdemeanor possession case heard.

Legal Aid lawyers defend most of these people. Said one lawyer, “The cops have their areas of concentration when it comes to these violations. Sometimes we’ll get a lot of arrests for so-called trespassing, which often means a person was caught hanging out in front of a project; it doesn’t matter if they live right across the street. But marijuana is very constant, a hardy perennial, you might say, rolling in regularly like the tide. The amounts are almost always tiny, which shows that for all the talk about going after the big guys, cops are mostly arresting low-end users. A lot of people say they were nabbed only minutes after they got the stuff, so it seems as if the cops are just sitting on known spots and busting whoever comes out. Most arrestees will receive an ACD, or ‘adjournment contemplating dismissal,’ a kind of probation. It is rare, but repeaters could get time. At the very least, it messes up your night riding around handcuffed in a paddy wagon.”

Harry Levine, a Queens College sociology professor who has been compiling marijuana arrest figures for years, says, “The cops prefer pot busts. They’re easy, because the people are almost never violent and, as opposed to drunks, hardly ever throw up in the car. Some of this has to do with the reduction in crime over the years. Pot arrests are great for keeping the quota numbers up. These kind of arrests toss people into the system, get their fingerprints on file. The bias of these arrests is in the statistics.”

The NYPD (good luck on getting the Public Information department to respond to your phone calls or e-mails on this particular topic) belittles these charges, saying the arrest stats are “absurdly inflated.”

The kicker in this is the apparently almost unknown fact that possession of 25 grams, or seven-eighths of an ounce—much more than the few joints that are getting people arrested—is not a crime in New York State and has not been since the passage of the Marijuana Reform Act of 1977, or 32 years ago. (Right here add sound of potheads slapping their foreheads, like, how come they didn’t know that?) There are exceptions, however. If the pot is “burning or open to public view,” then the 25-gram deal is off. It is this provision that has been the basis for the arrest outbreak, many civil libertarians contend.

The scenario of what happens on the street, as told to me by several arrestees, is remarkably similar. It goes like this: You’re black, or Spanish, or some white-boy fellow traveler with a cockeyed Bulls cap and falling-down pants. The cops come up to you, usually while you’re in a car, and ask you if you’re doing anything you shouldn’t. You say, “No, officer,” and they say, “You don’t have anything in your pocket you’re not supposed to have, do you, because if you do and I find it, it’ll be a lot worse for you.” It is at that point, because you are young, nervous, possibly simple, and ignorant of the law, you might comply and take the joint you’d been saving out of your pocket. Then, zam: Suddenly, your protection under the Marijuana Reform Act vanishes because the weed is now in “public view.” The handcuffs, the paddy wagon, and the aforementioned court date soon follow.

Now that he is ahead of Rudy’s numbers, Mike Bloomberg, who once famously answered a question from this magazine about his pot use by saying “you bet I did, and I enjoyed it,” has presided over more marijuana busts than any mayor anywhere. This could be compared with the record of another New York City mayor, Fiorello La Guardia, who, in response to the 1937 federal ban on pot, requested a report by the New York Academy of Medicine, which concluded that, contrary to Harry Anslinger’s claim that pot was an “assassin of youth,” marijuana was not medically addictive; not under the control of a single organized group; did not lead to morphine, heroin, or cocaine addiction; and was not the determining factor in the commission of major crimes, and that “publicity concerning the catastrophic effects of marihuana smoking in New York is unfounded.”

Once upon a mid-seventies time, the Yippies, then fronted by downtown immortals Dana Beal and the garbologist A. J. Weberman, staged a pot-legalization march up Fifth Avenue that ended in a rally at the Naumburg Bandshell in Central Park. The big attraction was a giant glass jar filled with joints; anyone picking the number of reefers in the jar would win it. The winner, some shambling longhair troglodyte, broke open the jar and threw the joints into the crowd, prompting a crush toward the stage. Alarmed, Weberman took the microphone and started screaming, “It is only crappy Mexican! Don’t kill yourself for crappy Mexican!”

“Ah, the good old days,” says Richard Gottfried, sitting in his state-assemblyman office on lower Broadway. Gottfried, who was a 23-year-old Columbia Law student when he was first elected as assemblyman from Manhattan’s West Side in 1970 (he’s been there ever since), is the author of the 1977 Reform Act. Hearing what people were saying about alleged police use of the “public view” phrase of the law, Gottfried rubbed at his still red-flecked professorial beard and said, “Why, if these searches are being conducted in this way … that would be a textbook example of entrapment, wouldn’t it?” He seemed shocked, absolutely shocked, that such practices were going on right here in New York City.

In 1997, Gottfried, a largely unsung hero of sane drug policy, wrote New York State’s first medical-marijuana legislation. “It stayed in committee a while,” says Gottfried. “With things like this, politicians tend to be very, very timid.” Nonetheless, Gottfried is confident medical marijuana is on the immediate horizon. It was passed by the Assembly in 2007, and Gottfried says it would have gotten through the Senate this past spring “if June 8th hadn’t happened.”

“Strange as it sounds, I think this is one issue that might actually be nonideological,” says Gottfried. “During the floor debate, these legislators, liberal and conservative, were almost in tears as they told their personal stories about how they and their loved ones had been helped by marijuana, how it brought relief from chronic pain, how it aided family members in last days of terminal diseases. It was quite moving.”

This doesn’t mean we should expect Californication 2 here, Gottfried says. “Medical-marijuana laws differ radically from state to state. There’s California and everywhere else.” In Maryland, you can’t be jailed for medical marijuana, but there’s no provision for obtaining it, which leaves elderly M.S. sufferers in the bizarre situation of having to potentially go out and score like a randy teenager. The New York version of the law will be “modest,” Gottfried says. As opposed to the “doctor’s letter” mills in Cali, permissions will be very carefully monitored, with legal possession limited to two and a half ounces. “The penalties for violating the medical-marijuana laws will be stiffer than regular possession,” Gottfried says.

What really mattered was that my kids understood that just because I used it didn’t mean they should.

If this was the best that could be done at this time, so be it. But why not simply be aboveboard about it? How many medical-marijuana patients are there really, at least compared with those who use the stuff for mental and emotional well-being, not to mention flat-out potheads?

You’re talking about recreational users?” Gottfried asked. “You’re talking about tax-and-regulate legalization?”

“Well … yeah. How do you feel about that?”

Gottfried smiled. “If marijuana had a similar status to liquor in this country, a locally controlled system of distribution, the way some states allow booze in the supermarket and some states are dry—I wouldn’t have a problem with that.” But I shouldn’t hold my breath, the assemblyman said. “We are in a period of transition. It could be a long transition.”

“I’m functioning in the shadow of something that is bound to change, except no one knows when or how,” says Francis R., who has been in the pot-delivery business for almost twenty years.

Mostly a painter “with some music thrown in,” Francis started off as a “runner” for a large Manhattan delivery service during the late eighties, in the wake of the massive drug sweeps like “Operation Pressure Point” that successfully ended the hard-drug street scene in many parts of New York. A gentrifying city had no place for such violence-prone local color. The delivery services, like the bar-based cocaine trade and the banishment of prostitutes from street corners and into “escort services,” where everything is done quietly and by appointment, proved to be a pragmatic compromise between law enforcement, human nature, and the need to keep the nightlife industry going.

In business for himself since shortly after 9/11, Francis has about 180 clients, of which 50 or so are “regular reorderers.” Employing an easy-to-park 250-cc. Japanese bike, Francis works “like 35 to 40 hours six days a week,” starting at around one in the afternoon. For this, he clears an average of about $150,000 a year, or about $1,000 “retail” on a crappy day and up to three grand on “a great day.”

Up until about 2004, Francis got much of his supply from Canada. “It was mostly indicas trucked across the country from Vancouver, then across the St. Lawrence Seaway, or Lake Erie. The first time I did this, I couldn’t believe it. It is totally dark, you couldn’t see ten feet. Then out of fog come these Indians … Indians, in canoes, paddling, like right out of the fucking Last of the Mohicans, bringing in the weed.” Eventually, however, the connection dried up. Some busts were made, but mostly the quality decreased.

Now everything Francis sells is from California. He recently made one of his regular trips to Mendocino County. “I had $25,000 in my suitcase, and some friends tell me to drive up toward Ukiah, to the Million Dollar Corner, which is called that because like a million dollars is changing hands there in pot sales like every other day. High as an elephant’s eye, dude.”

I took a pinch of Francis’s new stuff to Danny Danko’s “tasting,” as sort of a blindfold test to see if the experts would be able to identify the strain. This got kind of funny, these half-dozen pot gourmets investigating the inch-and-a-half-high bud, smoking it, poking it, checking out its tricombs under a magnifying glass like a no-shit Sherlock Holmes CSI team. Someone thought it was a clone of the original Skunk No. 1, others were certain it was in the Sour Diesel family. One gentleman, who referred to himself as a “pot snob,” put Francis’s high-priced spread down after a few tokes, declaring it “standard product … nothing to write home about.” He based this opinion primarily on the extreme “tightness” of the bud structure, which he characterized as “your typical ass pellet.” This was a sign of “insufficient curing,” the pot snob said, a giveaway that someone had rushed the crop. He also objected to the blackness of the ash and the fact that it had taken three match strokes to get the smoke going.

Francis was much put out by this assessment. “Everyone’s a fucking critic,” he protested, defending his weed. “Got you stoned, didn’t it?”

Francis said the cops weren’t all that much of a factor. “For the most part, I walk through the town unopposed.” But what about the busts?

“What busts?”

I showed Francis a copy of the New York State marijuana-arrest stats. He couldn’t believe it. He didn’t know a soul who had been pinched. He was not, however, surprised by the ethnic breakdown. “I hate to say it, but there’s no way I’m hiring a black guy to work for me. The chances of a black guy getting stopped is about 50 times more than a white guy. I can’t afford that. Fact is, pot is legal for white people but not for black people, which is total bullshit.”

Francis spends “a lot of time” thinking about legalization. “It is coming, not tomorrow or the next day, but it is coming,” he says. This is the general opinion among his colleagues, Francis says. “I’ve heard of guys buying liquor licenses, you know, to stay on the inebriation side of things.

“Can’t say I don’t have mixed feelings about it,” Francis went on. “I like this job. It’s served me well. Everyone is happy to see me when I come around. Can’t say that for a dentist. Still, it’ll be a great day if they legalize it. Because pot should be legal. You know what would really bother me, though? If gangster corporations like Philip Morris or Seagram’s got a big piece of the action. That would really chap my ass. Because, basically, with a couple scumbags here and there, this is an honorable business, a little-guy business. It should stay that way.”

Then Francis, being a swell fellow, told me he happened to have run across “a little something” just the other night, something sweet.

“You got sativa?”

Francis shook his head. “October … maybe late September. Maybe. But this Dog ain’t no bad dog.” He’d let it go for like maybe a nickel off, because I was putting him in a magazine article.

So I went down the road, to the F train, thinking about how I’d never drawn a legal puff of marijuana in my life. The scenic overlook of the paradigm shift shimmied before my eyes. I could already see the YouTubes of the near future, the debates raging over government versus corporate private-sector control, when every right-minded left-libertarian pothead knows either would be a disaster, a slo-mo shakedown to the Big Bud-weiser versus earnest microbrewers. No, it wasn’t going to be a total picnic when legalization came and people started scoring inside 7-Elevens instead of behind them.

And there was another issue. I’m not one of those potheads who wax on about the first time they got stoned with their kids. Sounds like a landmine from every angle. I mean, why make some moron hippie ceremony out of it? They knew I smoked, I knew they smoked, unless it was some burglar who stole my stash that night. Still, it is a crossroads, when you smell the smoke coming from their room. You feel obligated to tell both sides, even the D.A.R.E. side, citing all sorts of facts and figures, including how, according to a 2008 Australian study, men who smoked at least five joints a day for twenty years had smaller hippocampuses and amygdalas than nonusers. What really mattered was that kids understood pot wasn’t for everyone, that just because I used it didn’t mean they should. Young brains didn’t need that extra noise, I said, happy to set the legal pot-smoking age at 21, like booze, or at the very least the day a high-school diploma is attained. Beyond that, there is nothing left to do but to pray none of them has the addictive chip that makes people lose their good sense.

And, despite the best advice (“Whatever you do, don’t get fucking caught!”), kids sometimes can, and do, lose their good sense, if only temporarily. Really, pinched with a gram, in the middle of a celebratory smoke toast in honor of 420, the equivalent of pothead New Year. How does that even happen? So then, there you are, the pot dad and the newly crowned pot kid, sitting in the office of a court-mandated drug professional who is explaining why this two-month, four-nights-a-week, $10,000 program is actually the right thing, because “marijuana is a gateway drug.” At this point, the temptation is to cover your ears like a Munch painting and shout that mutual back-scratching between the criminal-justice system and high-priced treatment centers is one more reason that idiot drug laws have to go. But it is not that easy, because no matter how much you want the kid to get the same benefits from the mighty weed that it has given you, there is a deep conviction that it would be better if he didn’t smoke at all, at least until he gets his act together, which might take a lot longer than it has to if he keeps smoking. Still, it wasn’t like he needed some cop to participate in that decision-making process.

You can feel it, the war is on. A couple of months ago, the Times ran a big piece (“Marijuana Is Gateway Drug for Two Debates,” July 17, 2009) with updated Harry Anslinger–style quotes from poor souls made homeless by their marijuana problem. Words like dependence and habitual were prominently featured. The DEA is on record as being against the legalization of “smoked” marijuana for medical purposes. They say if people feel sick, they should take Marinol, a nice pharmaceutical that is THC without the fun.

Liquor was against the law for fourteen years. Pot’s been banned for 72. Neither the cartels nor the prohibitionists are going to just fold up and go away.

Not that I can worry about that. If I never smoke pot again, I’m cool. I appreciate what the stuff’s done for me already. I ask only one thing: Should I contract an illness that even grass, in its alleged miracle-drug mode, can’t cure, then just wheel me over to that guy sneaking a toke on the corner. I’ll breathe deep and, like the whiff of a just-baked madeleine, be transported to the place inside my head that’s always been home.

Originally appeared in New York Magazine Sep 13, 2009http://nymag.com/news/features/58995/

| The author of American Gangster, Mark Jacobson has been a contributing editor to the Village Voice, Rolling Stone, Esquire and New York Magazine. His most recent work is “The Lampshade“ |

Listen to The KGB Radio Hour featuring Mark Jacobson and Larry Ratso Sloman - http://www.kgbbar.com/radio_hour/

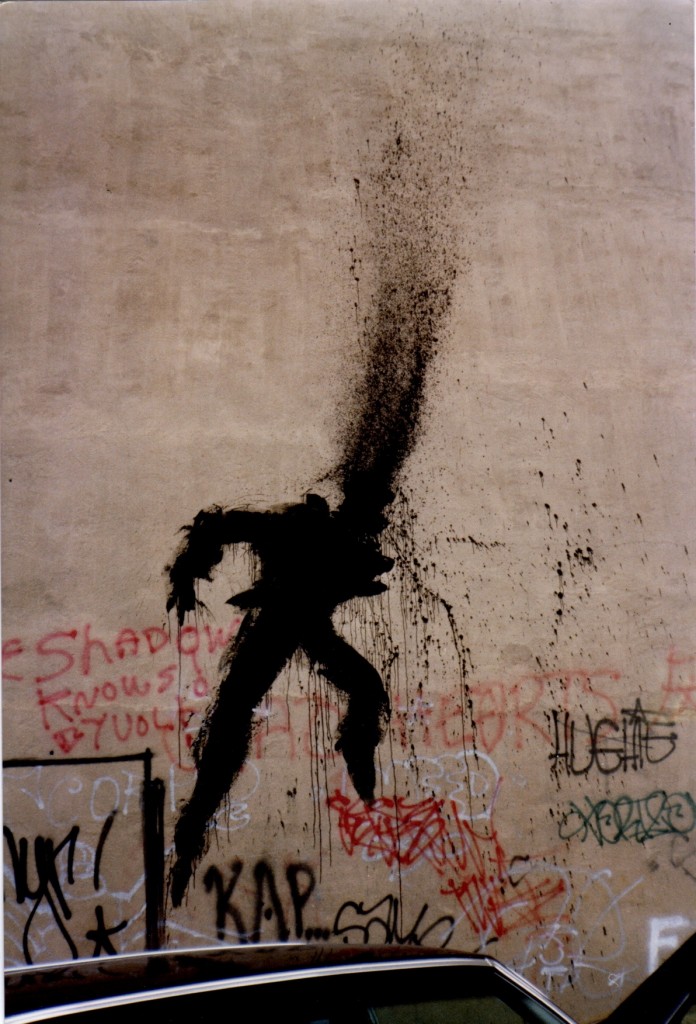

(Photo: Horacio Salinas)

(Photo: Horacio Salinas)