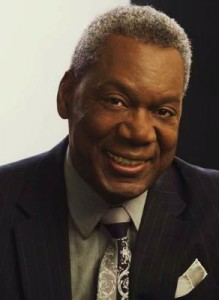

D’Army Bailey’s

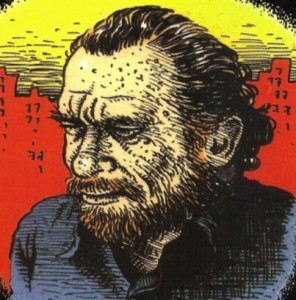

THE ORIGINAL X MAN

excerpted from his memoir

THE EDUCATION OF A BLACK RADICAL

The Black Muslim movement is a warning that Negro patience is not inexhaustible. The rights set forth in the Declaration of Independence and guaranteed by the Constitution cannot be denied to the Negro forever if he is expected to remain a loyal American Citizen. The Black Muslim Message of bitterness preached here by Malcolm X is a blueprint for disaster. Fortunately, most American Negroes so far are rejecting this counsel of extremism. But there is no guarantee that they will reject it permanently if their real grievances are not met without undue procrastination. Malcolm’s observations and analyses are as valid today as they were in 1963, with the exception of his strategies of racial separatism.

But Malcolm himself, by the time of his death in 1965, had moved decisively away from the separatist philosophy upheld by the Muslims. By March 1964, he had officially broken with the Black Muslims in order to organize a new movement with an emphasis on black nationalism and the conversion of the Negro population from nonviolence to active self-defense against white supremacists in all parts of the country. He said then that he would cooperate with grassroots civil rights activities wherever Negroes asked for his help because he believed every campaign for specific objectives heightened the political identification against white racism and their commitment to overcome it.

In a March 9 New York Times article titled

“Malcolm X Splits with Muhammad,” he wrote:

| There is no use deceiving ourselves, good education, housing and jobs are imperatives for the Negroes, and I shall support them in their fight to win these objectives, but I shall tell the Negroes that while these are necessary, they cannot solve the main Negro problem. I shall also tell them that what has been called the Negro Revolution in the United States is a deception practiced upon them because they have only to examine the failure of this so-called revolution to produce any positive results in the past year. I shall tell them what a real revolution means— the French Revolution, the American Revolution, Algeria, to name a few. There can be no revolution without bloodshed, and it is nonsense to describe the civil rights movement in America as a revolution. |

Malcolm’s developing black nationalist philosophies—philosophies of strong cultural identification, of determined group action, of political and economical realignment, and uncompromising force for self-protection— were sources of argument among black leadership for the rest of the decade. The “white man, move over” attitude threatened the old order of Negro leaders, the business and professional class and ministers, while at the same time seriously questioning the leadership of liberal whites in the struggle

against discrimination. It helped destroy the old stereotypes of the shiftless Negro and the Uncle Tom and brought to the surface not only a fiery racial pride but a widespread hatred for white domination. Disciplined to almost puritanical excess by the tenets of the Muslims, articulate, shrewd, and dynamic, Malcolm, even to his detractors, was an undeniably positive symbol for the New Negro: he was the young, dynamic, self-motivated Negro who no longer felt innately inferior to the white man. He embodied an assertive, uncompromising spirit, a spirit he insisted he knew the black masses shared. The philosophies central to the rising black nationalism of the late 1960s and to Malcolm X’s agenda during the last year of his life are certainly valid for any attack on black political, social, and economic inequity today. Ironically, they are probably more out of place today than they were in 1963, a consequence of what I think of as our philosophical neutering; we have not grown to full equality. And when we fail to grow with changing times, our position actually regresses. I believe that we have actually lost focus, momentum, pride, and belief in ourselves. We have lost that aching anger and drive for equality that brought us to confrontation in the 1960s. We have done the unthinkable: we have compromised.

Although Malcolm’s philosophy may appear more alien today than it did in 1963, his analyses are just as relevant in terms of the development, position, and condition of blacks vis-à-vis wealth and power in the United States. With a singular exception here or there, blacks are still sitting at the foot of the table getting the crumbs the white man drops. He still dominates the economy. He still largely dominates our government. Black people are still divided. We still have selfish and compromised leadership that thrives amidst our division. We still suffer from self-hatred and self-doubt. We still turn against ourselves with killings and muggings and shooting, acting like hoodlums and thugs—all the things Malcolm addressed. While poverty and the racial divide are still vast, Malcolm’s clarion voice is gone. It should not be forgotten.

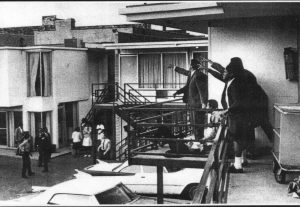

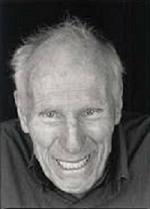

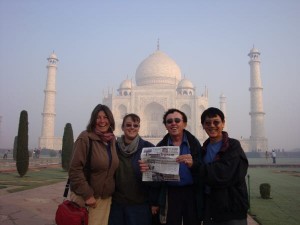

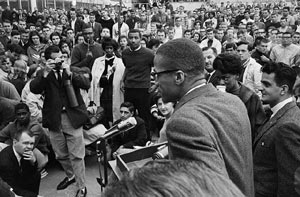

Memphis Circuit Court Judge D’Army Bailey was the founder the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel. One of the first Black Radical Civil Rights student activists in the 1960s, he was expelled from Southern University in Baton Rouge for refusing to give up his right to protest. He was rewarded with a scholarship to Clark University in Worsester, MA., where as one of the leaders of Student movement there he befriended and influenced (among others) the path of local townie Abbie Hoffman, and invited Malcolm X to be a guest speaker at the University. After graduating from Yale University Law School he served as a Radical City Councilman in Berkeley, CA, during the height of the Free Speech Movement. He was also author of Mine Eyes Have Seen: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’ Final Journey.

Memphis Circuit Court Judge D’Army Bailey was the founder the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel. One of the first Black Radical Civil Rights student activists in the 1960s, he was expelled from Southern University in Baton Rouge for refusing to give up his right to protest. He was rewarded with a scholarship to Clark University in Worsester, MA., where as one of the leaders of Student movement there he befriended and influenced (among others) the path of local townie Abbie Hoffman, and invited Malcolm X to be a guest speaker at the University. After graduating from Yale University Law School he served as a Radical City Councilman in Berkeley, CA, during the height of the Free Speech Movement. He was also author of Mine Eyes Have Seen: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’ Final Journey.

Malcolm X, the fluent young Negro who brought the message of the Black Muslims to Clark University the other night, talked mostly pernicious nonsense. His dream of an independent Negro state, freed of all relationship to the white United States, is a chimera. His indictment of the collective white man for subjugating and demoralizing the collective Negro is a neurotic syndrome. His arrogant dismissal of Christianity as a “white man’s religion,” and his claims of superiority for his version of the Moslem faith are psychopathic rubbish. Nevertheless, Malcolm X has a message for all Americans, white and Negro. For the fact is that his mood of bitter alienation from American life is shared, at least in part, by unknown numbers of American Negroes disillusioned by their slow acceptance into the American mainstream.

Malcolm X, the fluent young Negro who brought the message of the Black Muslims to Clark University the other night, talked mostly pernicious nonsense. His dream of an independent Negro state, freed of all relationship to the white United States, is a chimera. His indictment of the collective white man for subjugating and demoralizing the collective Negro is a neurotic syndrome. His arrogant dismissal of Christianity as a “white man’s religion,” and his claims of superiority for his version of the Moslem faith are psychopathic rubbish. Nevertheless, Malcolm X has a message for all Americans, white and Negro. For the fact is that his mood of bitter alienation from American life is shared, at least in part, by unknown numbers of American Negroes disillusioned by their slow acceptance into the American mainstream.