Mike Golden’s

Apocalypse When?

THE GOOD PARTS

Apocalypse When?

THE GOOD PARTS

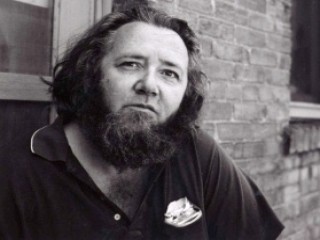

My dear old friend Jim Dickinson had a mostly unspoken umbrella philosophy for dozens of principles, theories, hypotheses, hypotenuses and probably hippopotamuses too, that he raised up from pups down on his north Mississippi Zebra ranch. As any self-respecting anthropological ‘pataphysical philosophical prankster prophet of the coming apocalyptic World Boogie would do, he always kept all his plates spinning at once, but all at different speeds, as he allowed the principles and theories that made up this philosophy to organically insinuate themselves into the various projects he was working on until they gradually embodied their own highest essence, and, one-by-one, were ready to be released, for better or worse, like the birthing process itself, into the outside world. The principal principle-theory of that philosophy that seems most appropriate to embrace slightly approximately a year after he checked out was called The Good Parts, which was a creative-editing system he envisioned to cut out the boring, mundane, sesquipedalian, cliché ridden stupidity of the ordinary and, very simply, only keep the good parts of the song, album, story, movie, poem, painting, book you were working on. How you actually went about doing that, of course, was not that simple, and hardly ever the same from one project to the next.

That was the truth of the joke, or if you prefer, the joke of the truth. Either way, when all was said and done, actualizing the good parts all came down to a matter of the artist’s own personal taste and aesthetic distance. If the so-called artist had none of one and didn’t have the patience to wait for the other, they were more likely to cut out the good parts (if there were any) than the bad parts, but ironically, as the buying habits of the great Mass Audience of Apocalypse (MAA) almost always proves, you have much more chance for being rewarded out in the polluted mainstream marketplace for something not very good at all than for something very good indeed, and you have much more chance of being rewarded out in the world for something false than you do for something true, indeed. This is not something any one of you out there riding along with my indulgence for the theoretical meaning of meaning doesn’t already know is the great chink in the conceit of the marketplace as a true measuring rod for the facade of Democracy. Lowest Common De’dumbass almost always rules in the marketplace, as the phenomenon of empty-headed conformists thinking they were Going Rogue climbed on top of Quantitative Slut Goddess known as the New York Times bestseller list last year like they had won free tickets to a gangbang to drill, baby, drill. Not long after that the world of corporate consumption went into deep mourning over the triumph of Tiger Woods lost sluthood. Of course, we in the cult ghetto would like to believe there are always exceptions to the rules of bad taste. But always is pushing the river of belief back up the whazoo of stagnant reality just a little too far for even a cosmic Owsley enema to unblock the passage, so let’s just simply say there are exceptions to the rule, and thank our lucky stars for The Big Bungler at least tossing us that bone of contention. Although if we who don’t-believe-in-anything-at-all believe in anything at this point, we must know those bones are really mistakes in a system that The Big Bungler deliberately designed not to work in the first place, thus providing us poor agnostic-bodhissatvic (turning-arthritic) souls down here on lonely earth the possibility of witnessing an occasional ooh-aww-ooh full court mind swish type miracle to diddle with the foundation of our sacred alienation. In short, it sort of gives you an edge if you know the critical question we all have to deal with at one time and/or many others is good old reliable To be or not to be. . . Dickinson savored that choice and that edge, but he was the exception to the exception.

It’s not a stretch of either personal history, or poetic license, to say Dickinson and I first bonded in a decrepit Music City brothel, when we were still wet-behind-the-ears 18-year olds. For whatever it’s worth in the long run, we shared a magical epiphany tossed at us by a mystical Adept pimp — Jim swears was named Archie, but I’m sure was called Fudge. It was the first lesson we shared as linguistic collaborators. A few days before that magical excursion into dialectical debauchery, our mutual friend Saulie, who had gone thumbing on the road with me and to high school with Dickinson decided to connect the two of us and hopped into the shotgun seat of Dickinson’s two door black 1950 Ford and they took off down Highway 100, from Memphis to Nashville, and didn’t stop again until they reached my parents’ house up on Love Circle, 200 miles away. My folks had left town for two weeks in the middle of August because I was safely ensconced in some shitty chain gang type job up in the wastelands of East Jesus, Indiana, and they thought their house would be safe with my main mole little brother taking care of it. Even before he let me know they had gone and I quit the job — selling $1 photo coupons door-to-door for some traveling flim-flam photographer buddy of the old man’s — and hitchhiked back home, smoke signals had been sent out to everyone I knew that I was throwing a party.

It was 1960, and there was something in the air. . .A couple of months earlier Dickinson had graduated from White Station high school; he had already finished a novel and left his band The Regents behind, convinced that he was “retiring from music.”

| The high bourbon-mark - as it were - of The Regents career was one night in 1959 at the National Guard Armory when we opened for Bo Diddley. That night there was this slight contract dispute. Bo Diddley - who was several hours late when he got there - he looked at the contract. Richard Sales - who was then president of TKO, putting on the dance - he had this contract. He says, “Now you’re taking one break - you’re here late already - now you’re just gonna take one break.” And Bo Diddley says, “No, I’m taking three breaks.” Richard says, “No, no - look down here in the contract - it says you’re taking one break.” Bo Diddley reaches in his pocket and he gets this little greasy square of paper and he unfolds it about twenty times and - sure enough - it’s the contract. And he says, “Yeah.” - he folds it back up and puts it in his pocket - “it says that in my contract too but I tell you what.” He points at me and says, “You could have been Bo Diddley,” - he points at Stanley and says - “or he could have been Bo Diddley, but I am Bo Diddley and Bo Diddley is taking three breaks.”

He took three breaks and we played the breaks. He was way up on a pedestal and (Danny) Graflund was trying to climb up there and get to him - so he could play his maracas - wearing a six-pack of beer on his head like an Indian headdress. It was a spectacular moment. Bo Diddley never came down - he stayed up there all night - and he looked down at one point, we were playing “Smokestack Lightnin” I think - and kinda gave us the thumbs up. Y’know, I thought I had it made at that moment. He had a maraca-player named Jerome Green and I decided that I was gonna get my first ‘theatrical’ autograph. So, I went into the bathroom in between sets. Bo Diddley is still up there but Jerome and Clifton, the drummer, went in the bathroom. Jerome was sitting in the urinal - with a hairnet on over his pompadour - reading a Batman comic-book. He autographed my guitar case - my Silvertone guitar case that I bought from new and wish I still had - “Jerome Green, Bo Diddley Band.” If Bo Diddley were here tonight, he would say. . .” We then launched into a cataclysmic medley of “Bo Diddley / Who Do You Love” and the fate of our souls - and livers - was secured forever. |

Within two weeks he would go off to Baylor College in Waco, Texas, to become a theatre major, and unbeknownst to him, one of the first CIA acid guinea pigs. We wouldn’t see each other again until four years later, in the summer of 1964, when he arrived with his “child bride” Mary Lindsay at our mutual friend’s wedding at the infamous Hotel Texas, in the stench laden shadows of the historic Forth Worth stockyards. A mere half year earlier Jack & Jackie and Lyndon & Lady Bird had all stayed in that same hotel – the same hotel they filmed Giant in in 1955 — before the President and his party boarded Air Force One the next day at Kelly AFB to make the short hop to Love Field in Dallas, for what would become the beginning of that long weird trip ahead, from the Book Depository to the grassy knoll and on. . .

Another four years passed before we hooked up again. I had written a novel of my own by that time, and was camping on an old college roommate’s couch in midtown Memphis, finishing a second one based on my half-crazed experiences working another shitty job as an undercover industrial trade spy for Coca Cola, when it occurred to me I actually knew a real writer, someone I could talk to about the shit I was doing. Which was when we first started hanging out in earnest and reading our writing to each other.

One afternoon, he passed a small, frog-shaped pipe to me as he began offering feedback on what I had read to him. His comments seemed totally irrelevant, yet they spun my head 360-degrees and bought me a ticket on the first tangent to catharsis. It was almost as if he had explained what an apple was to me, and for the first time I suddenly understand the composition of an orange. In some unintentional way, it seemed like Dickinson was showing me how to perceive my own process. But when I thanked him for the insight, he exploded (like the drums on The Replacements’ I.O.U. would years later) and barked, “You’re doing it yourself! THE TEACHER IS THE ENEMY!” Though most fairly conscious seven-year-olds suspect that the moment they first step into a classroom to be indoctrinated into the system, I had never heard it put more bluntly. But maybe the profundity of what we both took for granted came from the weed. It often did, in those glorious days.

Dickinson laughed at the suggestion. For six months, he explained, he had been driving out to pick up Mary Lindsay at the Germantown stables where she trained jumping horses. While waiting for her to finish, he would wander around, ducking into barns, tack rooms - any place where no one else was around. He would always notice the spiderwebs. At first it was instinct, he rationalized, not knowing why he began collecting them. But as the webs grew into a huge ball of filth, inspiration took over. When the ball got big and hard, he actually washed it. Then dried it. And dried it. And dried it. Then let it sit out in the sun for a month.

“We’re smoking it now,” he cackled. It was the kind of infectious howl that could instantly start a crescendo of out-of-control side-splitting, tear-stained whooping for dear sweet life, even in a morgue. Which was when I realized that the right half of my body was totally paralyzed!

“Mine too,” Dickinson whispered.

When I asked how long it would take for the numbness to go away, he admitted he didn’t know. “This is the first time I’ve ever smoked it.” By this time he was laughing so hard tears began rolling out from under his glasses, down his cheeks. This was obviously a man who relished leaping head first into the unknown and spitting in the face of the void. Despite a surge of fear rushing through the half of my body that wasn’t paralyzed, I suddenly started laughing too. And couldn’t stop.

When Mary Lindsay finally came home from the stables five or six hours later, she found us sitting there, still unable to move, but still laughing like we had found Uncle Remus’ fabled Laughing Place and couldn’t get out of it.

I’ll definitely miss that contagious laugh. I’m sure I became so addicted to it over the years that whether it was conscious or not I not only must have played to it in my writing, but in some astonishing ways probably always will. Though the order of the time frame is little cloudy now, it’s all there, from all those afternoons we spent hanging out together (because he worked nights at John Fry’s Ardent Studios teaching himself to run the board, and beginning the transformation that would take him from an out of work novelist and boogie-woogie piano player to one of the most influential off-beat raconteurs, cultural historians and music producers of the next four decades), to continually staying in touch by letter and long distance, up until the last five or six years, when we dropped the letter and talked on the phone regularly two or three mornings a week (right up to the day before he went into the hospital for the last time). Mostly we were kicking around what people we knew were doing or not doing with their lives, going back to ideas we had shared over the years about different events, writers or performers, laughing over our mutual nightly fix of Chelsea Lately’s assault on censorship, attempting to collaborate with each other on various projects, ranging from a blues operX centered around the King assassination, to a hard core Private Investigator tv series set in Memphis - with a character based on his alter ego Little Lorenzo narrating the action — to him enthusiastically agreeing to edit a special music issue of Smoke Signals. . . Basically it was an unfinished lifelong jam session, integrating the personal with the deeper philosophical meaning of those immortal words that that grand pimp had laid on us, to the absurdity of his father sending him off to college — with a lesson to remember for the rest of his life — after he heard what a low rent dive his son had frequented in Music City, to what happened to him when he finally went off to college – always what happened to him at Baylor – to pondering whether the presence of the ghost of James Dean had drunkenly wandered into Saulie’s wedding when the band played The Eyes of Texas instead of the wedding march in the same ballroom they had used 11 years earlier to shoot Jett Rink’s classic pathetic – looking back alone on his life — drunk scene in Giant, to seven years later Richard Pryor calling Dickinson’s house looking for me to come back to NYC (after I had just escaped) to work with him, to Jerry Wexler blowing the opportunity for Atlantic to sign Pryor after I brought That Nigger Is Crazy to him on a silver platter, to Jim being in the right place at the right time to play piano for the Stones on Wild Horses, only because Ian Stewart couldn’t stand playing minor chords and the song began in B-minor, to the whole crazy Dixie Flyers recording experience down in Miami, to the stolen at gunpoint first interview (of hundreds & hundreds he did) in his career that (the then rock journalist) Lenny Kaye did with him (for some Men’s mag) when he came to NYC to promote his first album Dixie Fried. . . I’m sure most of these incidents will be in Search For Blind Lemon, the memoir he worked on for years, and finished right before he got sick.

The final words he left behind to calm his upset family and friends was a perfect summation of the situation if there ever was one. Though I wasn’t bedside in-person at the end, I can still hear his laugh in my head like an internal tuning fork, singing out, “I’m just dead, I’m not gone.”

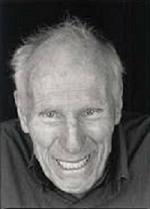

| The Godfather of postpunk mutant funk, Jim Dickinson was (and still is) a Contributing Editor to Smoke Signals. He can be found singing Mark “Butch” Unobsky’s ASSHOLE in the spring 08 issue http://smokesignalsmag.com/2/ and singing Dave Hickey’s BILLY & OSCAR in issue 09#1-2 http://smokesignalsmag.com/4/wordpress/ . He took his leave of absence Aug 15, 2009, with the words,

“I’m just dead, I’m not gone.” His work can be found and purchased from http://www.zebraranch.com/ The two cuts enclosed here – 1. HARD TIMES and WHEN YOU WISH UPON A STAR

are from his recently released album Dinosaurs Run in Circles. |

http://www.commercialappeal.com/news/2009/aug/15/memphis-musician-jim-dickinson-dies-67/

I’ll definitely miss that laugh. I’m sure I became so addicted to it over the years that whether it was conscious or not I not only must have played to it, but written to it, and in some ways probably still am. If I don’t hear that cacophonous cackle in my head telling me to “Shake hands with your Uncle Death, my son,” the internal tuning fork says, it just ain’t right yet.

And speaking of right on tuning forks, Budge Threlkeld must have had one built directly into his soul. Unlike the long winding pot-holed roads Dickinson and I explored, Budge and I met and bonded in the flash of one night in the early ‘90s, after he blew me away doing standup downstairs at Steve Olson’s Westbank Café Theatre bar on what was then known as Theatre Row. I’m not sure if you would call what he did comedy, philosophy or sorcery, but it was without a doubt the most outrageous combination of all three I had ever seen on a stage before, and once back in the fall of ’71 I had spent 10 consecutive nights at Sam Hood’s old Gaslight club with aforementioned Pryor, pointedly watching him crossover the line from being a great standup on the verge of breaking through to the other side, to a certified genius, to an actual shaman modulating the human condition. What Budge did was different than Pryor though. What Rich had done was hone the same material (he had been working on for years at the Whiskey and other clubs on the hip circuit) so finely down to the bone, that only the good parts were left, and he actually conjured up his immortal Mudbone into a character so real, that the audience was uncontrollably laughing and crying at the same time all through his act. Night after night, for all 10 nights of the run, though as he told me half-way through, he was only in his body a few of those nights, and on auto-pilot for all the others. The audience didn’t know the difference, but by the end of the run, I thought I could tell whether he was there or not. Either way, I had never seen anything like it before, nor have I seen anything like it since. What Budge did was different though; while Pryor walked on the stage as a comedian and walked off as a shaman, Budge walked on as a shaman and walked off the stage after 90 to 120 minutes of intravenous improvisation as the psychedelic manifestation of the inner workings of everyone in the audience’s own twisted minds. I remember turning to the person sitting next to me and asking, “Did he just blow himself on stage?” Whatever it was he did, it was as close as anything I’ve ever seen to the snake eating its own tail over and over again, until the full quart of Tequila he had walked on stage with was finally empty and the act was over. Though in truth, the act was never over (because it wasn’t an act), as I learned drinking with him in different bars all over The City every night for the next five nights. I never saw him, or was in direct contact with him again after that week, which was the week prior to him officially retiring from doing standup full time and moving to Orlando (for his health) to manage some kind of comedy club in – believe it or not - Disney World. That image of him was too hard to fathom, but I kept up with how he was doing long distance through our mutual buddy Mike Simmons. Which is how I learned he had passed on – and how I learned from the on line memorial obituary guest book (http://obit.memorialobituaries.com/guestbook.cgi?id=230342&print=1&clientid=montgomerysteward&listing=All) that almost everyone who met him felt just as passionately about him as I did — and how just over a year ago the whole process of looking for tapes to document the unknown sorcerer’s standup career began.

“Contact Bill Frenzer,” Mikey told me, and gave me an email address. “Call Steve Ecclesine,” Bill said, and gave me a phone number. From that moment on we talked quite a bit about our standup sorcerer brother, and when I told Steve my impression of Budgie’s standup act, he told me that what Budgie used to do was walk out on the stage of whatever club he was working and start telling a story, then half way through that story he’d wander over to a table in the audience and casually ask the audience member what they were drinking, pick up their drink and finish it for them, and as the house replenished their drink for them he would wander back on stage and go off on a tangent as he begin telling an entirely different story. Then about half way through it he would wander over to another audience member’s table and casually ask them what they were drinking, pick up their drink and finish it for them, and as the house replenished their drink for them he would wander back on stage and go off on a tangent as he began telling an entirely different story. By the seventh time he finished someone else’s drink and wandered back on stage the tangent he would go off on would turn into the second half of the first story he had told. When he finished he would wander over to someone else in the audience, pick up their drink, and go through the whole routine again until he was telling the second half of second story he had told. And then, between audience drinks, the second half of the third story, and then the fourth, and then the fifth, and the sixth, until he finally finished the second half of the seventh story, and the act was over.

From that point on it was a matter of Bill and Steve rescuing hours and hours of old tapes stored in warehouses out in the Valley, and transferring them to DVDs before they turned into dust. Then picking out about five minutes of Budge doing standup that Andy Bobrow and I cut cut down to Why Aren’t You Laughing?. There’s obviously a lot more of Budge where that came from, and must be uncalculated hours more of his alter-schtickster Sam Diego stored all over L.A. and Disney World that we’d like to rescue and hone down to the good parts before the end of the world (which seems like a pretty good theme for the next last issue – because every issue (including this one) feels like the last issue unless we can get a little action from the still breathing out there who are capable of jumping in and joining us). Or as Dickinson’s barker double might have huckstered on his Dixie Fried cut of O How She Dances, “Step right up, ladies and gentlemen. . .and tell your friends, family and children, or they will reproach you in later life for this lack in their education. . .”

“Here lies RAYMOND FEDERMAN who thought himself immortal until he was proven wrong.”

Federman’s self proclaimed epitaph from Smoke Signals 1982 Fools’ Day jam issue –

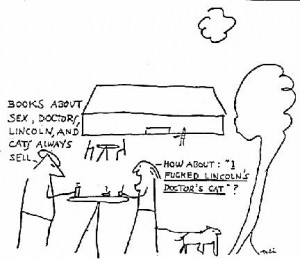

Segueing into Federman from the line lack in their education could have been the theme of a Federman novel, or just a cheap trick to get from here to Double Or Nothing. Either way, I was introduced to Federman’s work in the early ‘70s by a literary agent we both shared, and ended up getting to know him really well for close to 30 years, though we never, in actuality, met, or talked even once, unless you count old fashion snail mail, or emails. His Double Or Nothing and Take It Or Leave It were primers in the joy of writing pata-meta-(from now on let’s call it) federfiction (for lack of a better word), and unless you had a tenured batcave covering your ass in academia would almost totally ruin any chances you might have (if so inclined) to sell out and go commercial for the boys, as the priestly Pat O’Brien said to Cagney’s Rocky right before he went to the chair in Angels With Dirty Faces. For that we thank him and curse him and celebrate him and love him. In the early days, Smoke Signals published his fiction (from Two Fold Vibration), poetry and self interviews, and several years back he contacted me and said he wanted to translate my less than respectable hymn to the Beats, Bring Me The Head Of Gregory Corso (http://www.corpse.org/archives/issue_7/burning_bush/golden.htm).

Federman’s longtime relationship with Samuel Beckett was well documented, so it’s not surprising, that as he neared the end he began writing of him again. Here’s a poem about reading Beckett that he wrote when he saw all too clearly how close he was to death:

-

- A Matter of Enthusiasm

I am rereading Malone Dies

just to mock death a little

and boost my cancerous spirit.I shall soon be quite dead at last

Malone tells us at the beginning

of his story.What a superb opening

what a fabulous sentence.With such a sentence

Malone announces his death

and at the same time delays it.In fact all of Malone’s story

is but an adjournment.Malone even manages

to defer his death

until the end of eternity.That

soon is such a vague word.How much time is soon?

How does one measure soon?Normal people say

I’ll be dead in ten years

or I’ll be dead before I’m eighty

or I’ll be dead by the end of this week

Quite dead at last

Malone specifies.Unlike Malone prone in bed

scribbling the story of his death

with his little pencil stub

normal standing people

like to be precise

concerning their death.Oh how they would love

to know in advance

the exact date and time

of their death.How relieved they would be

to know exactly when

they would depart from

the great cunt of existence

in Malone’s own words

to plunge into the great lie

of the afterlife.How happy they would be

if when they emerge into life

the good doctor

or the one responsible

for having expelled them

into existence

would tell them you will die at 15:30

on December 22, 1989.Could Sam have written

I shall soon be quite dead at last

had he known in advance

when he would change tense?Certainly not

because as Malone tells us

a bit further in his storyI shall die tepid

without enthusiasm.Does that mean on the contrary

of those idiots on this bitch of an earth

who explode themselves with fervor

to reach the illusion of paradise

while taking with them other mortals

that Malone’s lack of enthusiasm

towards his own death is a clever way

of delaying the act of dying?A lack of enthusiasm for something

is always a way of postponing

the terms of that something.The soon of Malone mocks

the permanence of death

and his lack of enthusiasm

ridicules the expression at last.And so before he reaches the end

of the first page of his story

Malone has already succeeded

in postponing his death to

Saint John the Baptist’s Day

and even the Fourteenth of July.

Malone even believes he might be able

to resist until the

Transfiguration

not to speak of the Assumption

which certainly throws some doubt

as to what really happened

on that mythical day

or what will happen to Malone

if he manages to hang on until then.In fact Malone defies his own death

by giving himself

birth into death

as he explains at the end of his story.All is ready. Except me. I am being

given, if I may venture the expression,

birth to into death, such is my impression.

The feet are clear already,

of the great cunt of existence.

Favorable presentation I trust.

My head will be the last to die.

Haul in your hands. I can’t.

The render rents, My story ended

I’ll be living yet. Promising lag.

That is the end of me. I shall say I no more.Nothing more to add this evening.

Malone said it all for me.

I can go to sleep calmly now.

Good night everybody.

’06 Federman Inner-View - http://www.raintaxi.com/online/2006fall/federman.shtml

’09 Federman Blog (the laugh that laughs the laugh) - http://raymondfederman.blogspot.com/

Federman Home Page - http://epc.buffalo.edu/authors/federman/

Federman on the air - http://wings.buffalo.edu/epc/linebreak/programs/federman/

As Federman’s blog states, Do something strange and playful today. That’s not only how he would have wanted to be remembered, but a sentiment both Jim and Budgie probably would’ve embraced too.

Dickinson was a compulsive collector of other people’s material he loved, as the wide variety of songs he championed by writers — as different as Tex Ritter, Dave Hickey, Mark Unobsky and Bob Frank – show. Federman’s writing always paid tribute to the work that influenced him, whether it was from Beckett, Dostoevsky or the jazz musicians he so much wanted to be one of. And though I’m not sure exactly what Good Parts Budge collected, I’m betting the material that influenced him was like an inbuilt family he carried with him his whole life.

I’m no different in that regard. Ever since I started writing I’ve filled notebook after notebook with my favorite passages from books by other writers. I could leave you with a couple of books full of the good parts I’ve collected over the years, but here’s one to chew on, until we tackle the end of the world next time.

| Once upon a time there was a man who had a pimple in the middle of his back. Try as he might he could not reach it, and the pimple grew bigger and bigger. So big, in fact, that it became a question of whether the man had the pimple or the pimple had the man. Whichever was the case, the two of them were out walking one day when they happened to meet a pure pimple, that is, an unattached pimple, which was, from a pimplish point of view, a very handsome pimple, Red and shiny and taut with a great white head like an albino volcano. The handsome pimple, seeing the other pimple so badly blemished by the rough hairy man, said, “You should really do something about yourself, my dear. You could be a very attractive pimple if you only took care of your complexion.” Whereat the pimple with the man began to cry. “Don’t worry, don’t worry,” the handsome pimple said, “I’ll take you to my dermatologist, and in no time you’ll be on your way to beauty and happiness.” And that very day the handsome pimple took the blemished pimple to the doctor. The doctor shook his head and clicked his tongue and said that in his entire career he had never seen anything like it. “But I think we can help you,” he said, whereupon he put the pimple up on a leather table, removed the scraps of clothing that adhered to the man, and with the help of a nurse squeezed the man until he burst! O what a relief for the pimple! “Now, keep this bandage on for a week,” the doctor said, “and don’t worry about a thing. You’re going to be all right.” And sure enough after a week, when the bandage came off, only the tiniest scar remained where the man had been.

- Charles Simmons / Powdered Eggs - |