Victor Harwood Interviews

Regis Debray

Regis Debray

“I will never plead for pardon for the defeated. I will never address you as victors. On the contrary, I will tell you that although I am certain I am innocent of the charges made against me, to you I am guilty for believing in the final victory of Che in the near future, guilty for wanting to fulfill the pledge irreversibly contracted by anyone who has had the privilege of witnessing Che live, think and fight, the pledge of remaining faithful to him and following his example, as far as he is able, to the last. “I will do my best to deserve one day the extreme honor that I will be surely granted when you condemn me for what I have not done, but wish to do now more than ever. And in all serenity, with all my heart, I thank you beforehand for the severe penalty I expect from you.” Régis Debray before a Bolivian Military Court, 1967

Four days after the death of the mythic Argentine revolutionary figure Che Guevara, Régis Debray, a French journalist in his twenties, sat in a Camiri, Bolivia jail sentenced to 50 years for attempting the revolutionary overthrow of the Bolivian government. Debray was known worldwide as the author of Revolution in the Revolution, a book which in those years, was used quite literally as a roadmap in how to design and execute a guerilla-fought revolution. In the 1960s Debray became an associate of Fidel Castro and in February of 1967 he sought out Che Guevara and his band of guerrilla fighters. During an ambush on a Bolivian Army patrol, he was captured.

The following excerpt is from an interview by Marlene Nadle which appeared in Ramparts magazine during the summer of 1968:

DEBRAY: Che was a very authoritarian man. In the guerrilla camp he would simply say, ‘This is the way it will be.’ Che did not support discussion. Fidel would support discussion but Che would not. He was very hard. Very rough, but sometimes with some people he was very tender, very sentimental. I think he had two personalities. He said on the night after the death of a comrade, ‘a communist must make himself hard without losing the tenderness. . .’ Hard? That’s not the word. I can’t express it in English because, you know, it is impossible to speak about Che Guevara in English. You can only talk about him in Spanish and maybe in French because he knows French. He spoke French very well. But English, impossible! You know what a sacrilege is? (Debray asked with a smile). Well to speak about Che in English is a sacrilege. To put Che in a Yankee situation is a sacrilege because all the sense of his life was to fight against the Yankee and against . . . I don’t say against the American people, but I say against the American way of life, and against the image of life an American has, against the lack of soul American people have. Impossible in English. . . Che loved Fidel. He had a respect and an admiration, a kind of moral brotherhood, a sentimental link with Fidel that was very profound, very deep. Che always said it was Fidel who made him a revolutionary and a communist, that he had a debt to Fidel. He always considered himself second to Fidel. That’s why he once said to me, ˜Fidel is only one; the Ches are many.` “Both of them were always strong men, forceful men, but in different ways. Naturally, or physically, Fidel is stronger. Che was a weak man, physically. “Well, to tell it in one word, Che was an intellectual, you know, and Fidel is not an intellectual. Fidel is a genius! A genius by intuition, . . . Che said one day that Fidel was a natural force. Che was a man of reflection, a man of thought.

Debray asked his interviewer where she was from.

Her answer was, “New York, from the Village.”

“The Village? But what is the Village: Beatniks? LSD? Ginsberg?”

“Politicos.” she answered.

“Politicos? The left, the American left, is what are they: Monthly Review? Monthly Review was denounced by Fidel two years ago and I think Fidel was right. Even if we know the editors are good men. Good men? We were working with them! We made the work of the enemy! They published a lot of false things. Attacking Cuba and attacking Fidel upon wrong things. Telling that Che was dying! That there is not any liberty in Cuba! That the Trotskyists are in jail in Cuba! A lot of silly things. And that is the American left. They are the good Nazis. How can we trust them?”

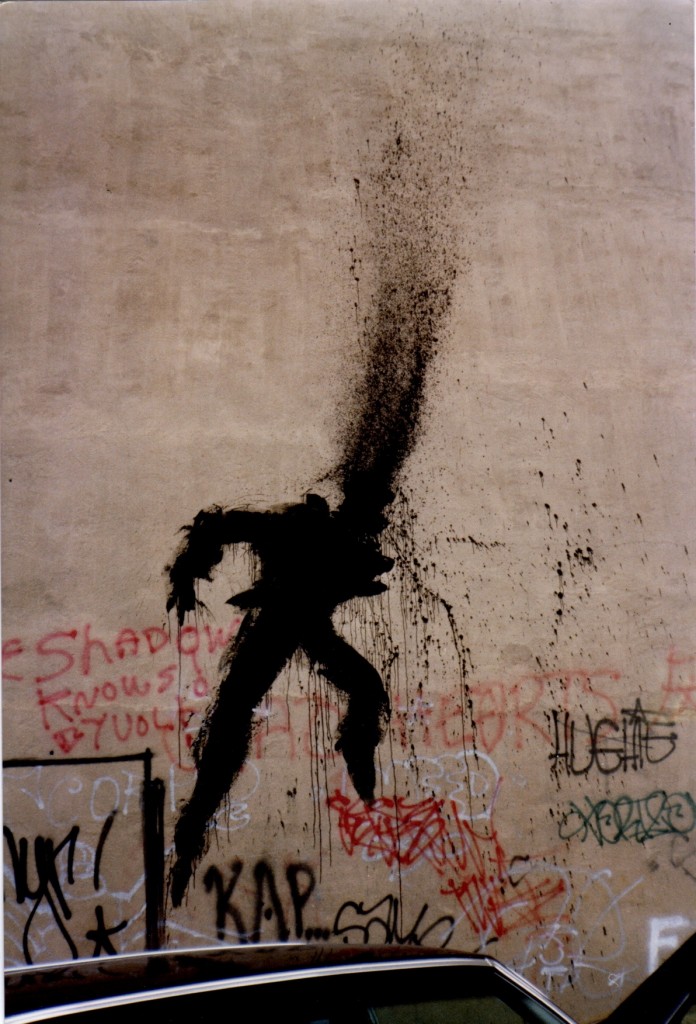

At the conclusion of his interview, Debray said that Che “had the same conception of death as Fidel or Marti. That is, death as a promise of rebirth. Death as a sort of acceleration of life, a kind of ritual of renewal. “And with his death, I think we have a decision we didn’t have before. This decision is to go until the end. I think now we know that everybody must fight and everybody must die in this fight. Bolivar spoke of a guerra a muerie, a war until death. Now we are all very near some guerra a muerie.”

Victor Harwood: In 1981 you became an official advisor to the Socialist Government of France. Can you explain to us the circumstances.

Regis Debray: In 1981 I was given the mission as international advisor to Francois Mitterand, the President of France, with special interest in Third World affairs. Why? Because even though I am not a Socialist, not a member of the Socialist Party. I am a left wing intellectual and I had been in contact with Mitterand since 1975 when I had returned to France following the Chilean coup and the end of my Latin American adventures. So I had long a friendship with Francois Miitterand and when he took power it was very natural that I should become one of his personal staff.

Harwood: So much has changed in 25 years; Gorbachev in Russia, the Chinese have private enterprise, yet in Cuba, Fidel remains a hardline Stalinist. It seems inevitable that communism in Cuba will fade. How can Cuba withstand what is now a Cuban-American onslaught - the “Miami Sound Machine` - rock and roll from Miami, computers from California. Why doesn’t Fidel open his country, join Baseball’s Major Leagues and take the Havana team to the World Series. Surely it will come. One month after Fidel dies, the first non-ideological prime minister of Cuba will surely make a baseball deal with Donald Trump. Why should Fidel deprive himself and his fellow countrymen the pleasure of meeting Willie Mays? Is it possible to set a new non-ideological agenda?

Debray: I understand you. The Shah of Iran had ideas like this 20 years ago. He thought that the petro revolution and the communications revolution were going to insulate his country. A television set in each house - all this modern power resulted in a man called Khomeini. Modernization went so fast that it actually raised the Khomeinian culture. Modernization brought the countryside to the city and with it came the ideas of the country fundamentalism had come to the cities.

Harwood: Is this discussion of Khomeini a metaphor for our relationship with Cuba or might it be something else?

Debray: I am sure that you don’t like to speak of Khomeini because it looks to be outside of your consciousness or hemisphere. But try to think that the ideas that seem the most out of your sphere may hold the keys to understanding life best. Do you know that all of the fundamentalist leaders in Egypt. Syria. Morocco, Tunisia etc., were educated in the science faculties. not the letters faculties of the universities - from the men that studied mathematics. You must understand that there is no antithesis between religion and science. The real problem of tomorrow is between God and computers. Evil and Computers. The more you have computers, the more you will have a need for God and for evil. lt is totally absurd to imagine that you can sweep out God and religion and archaism with computers. All contemporary history shows that all things are progressing together. In all the world around we have a tremendous religious upheaval. of national movements and struggles. Look to Ceylon where the Buddhists are fighting, Armenia and the Christian faith, Lithuania, the Ukraine and all over Russia. The more the Soviet Union is modernizing itself, the more its people revert to the archaic roots of their identity.

Harwood: You are saying that it is the power of the traditional religions that has defeated Stalinism. Does that pertain to Cuba as well?

Debray: Communism, or Scientific Socialism is not a very profound religion and obviously in Cuba the Communist faith will disappear under the shock of American culture. You spoke of baseball . . . you know that we don’t have baseball in France. You have baseball in the American spheres of influence, Columbia, Venezuela, the Caribbean. But there is no baseball in China. No baseball in France, in the rest of the world.

Harwood: You are making fun of us now. Baseball and hamburgers. We are so primitive and boring, no?

Debray: For me it is so boring. When I was with Fidel Castro, he brought me to the stadium to see boring things. All the time I was bored. Bon. Now, to come back to the subject. I think that you are totally right. Cuba has a big love affair with the United States. Fidel Castro is in love with the United States. Of course hate and love and love and hate. That is the weak link in the chain. Rock music from Miami and computers will sweep out Communism in Cuba and I think that he knows it. That’s the reason why he blocks everything. He doesn’t want to see it happen as long as he lives. I am sure you can destroy the Communist ideology, but you can’t destroy the Muslim ideology, the Catholic ideology - these are very deep and serious things.

Americans think that history is made by technology. Europeans have a more complex view of the situation. They don’t believe in a purely technological determinism in terms of evolution. Technology has no impact on the evolution of history. There are two histories within history. There is a technological part, which can be linear, and there is the political part that is tied to the unconscious state of the individual. This doesn’t mean that there is no relationship between the two kinds of history. The history between man and things is a technological history. The history of the relationship between men and men, the history of passion, doesn’t have a history.

Just because technology can destroy socialism doesn’t mean that it can destroy the great and historical religions. L believe that you are trying to present a case for the Third theory. This is not at all my conviction. By entering the new technological world we are coming back at the same time to our archaic roots. The more we will go further and far with technology, the more we will come back to the past in a cultural reaction toward sustaining our original identity.

Harwood: Can we look into the future? What will France look like in 25 years?

Debray: That is a good question. France may become a very nationalist country with some new ethnic discovery of itself - traditional music - we may have a left-wing reaction against the American way of life. I am not sure. France will necessarily drift toward becoming a European Puerto Rico. I am not sure of that, but we are drawn toward that American culture . . . but don’t forget the backlash.

Harwood: Twenty years from today technology may not rest in the hands of Americans. As the power of a microcomputer approaches the power of a mainframe, who is to say that the ability to create mass culture will have substantially altered? There will no longer necessarily be an America-phobia concerning entertainment because many people or countries will have been empowered. We in New York may be complaining about the proliferation of French import television shows on our airwaves.

Debray: We agree. As the Marxist says, science has become a means of production. Intelligence has become a means of production.

Harwood: But I am suggesting that there will be a non-ideological, non-nationalistic world.

Debray: You`re right. but don’t forget that the human being needs to belong to something, a country, a community. The more the man will exist in a technological world, the more he will have a common psychological structure to identify himself with.

Harwood: Can ideology exist outside of state of violence? Anything less is a difference of opinion - a cup of coffee.

Debray: I share your view. The main point in the history of society is whether you are willing to die for what you believe in. I should say that in France now, the common idea is that nothing is worth the life of a man. The men who are with Khomeini believe that death will bring them to paradise. so that he has a tremendous moral force even if it is a reactionary one and I wonder whether in the United States or France, if it were decided that we murder Khomeini, I wonder how many volunteers would present themselves for the task? Everyone here is in favor of human rights, democratic rights and so on, but how many are willing to give their lives for these things? I don`t know and I suppose that Khomeini knows that we don`t know.

Harwood: Your theory of archaism, the grasping on to original roots strikes me as a repackaging of the old defeated ideology - nostalgia for one that has died and to replace it with another and even older one. I will suggest that the Russian

regional rights and religious movements are more meaningful as symbols of a failed communist ideology than they are the establishment or an assertion of an older, stronger and essentially more sound ideology.

Debray: I don`t know what you want from me. I am not a modernist, I don`t think modernism is an answer to everything. I don`t believe that there are only social

answers to problems of society - man is basically religious and I understand that this is something of a reactionary point of view.

Harwood: Can you express this in American terms?

Debray: The United States will become more nationalistic, imperialistic, self-centered due to all of the revolutions in technology. I am very impressed by religious appeals by Jesse Jackson and by the televangelist who ran for the president, Robertson. It is a strange thing, but in a society that is so apparently modern, you have so many religious political leaders - on the right wing and on the left.

Harwood: Diversity is so well built into the body politic that American television can give over entire channels to minority opinions - the religious channel, the sex channel, the Q shopping channel. Are these religious votes more likely an expression of our diversity as opposed to signaling what is to come?

Debray: There is no zero sum game between religion and the technological revolution. The more you will have a need for information, the more you will have a need for not having information. Religion will play an important role in the United States and an even more important one in the Soviet Union because Gorbachev will try to maintain a profoundly lay, nonreligious society.

Harwood: How sensitive do you believe our new President is to the religious movements, the Khomeinism in the world?

Debray: It is very difficult to understand current history. Who could imagine that the main threat at the end of the 20th Century would be the upsurge for defending the beliefs of Mohammad? It seems totally absurd. On one hand you have TV, networks, computers, and on the other you have a billion people with their Islamic faith. You seem to think of the technological movement as the serious one and the religious movement as the superficial and short-term problem.

Harwood: That is what I think?

Debray: I fear that is the fact.

Harwood: Concerning Klaus Barbie. Did you return to Bolivia in an effort to capture Barbie and return him to France?

Debray: I didn’t return especially for that purpose, but when I was in Chile during the Allende years. l972-73.

Harwood: This is after your release from the Bolivian jail.

Debray: One or two years later I got involved in a kidnapping enterprise with a few fellow Frenchmen.

Harwood: How far did it get?

Debray: Not very far because he was well protected and we did not have the money for the proper equipment, the cars and so on. It was a very romantic affair. but not an interesting one.

Harwood: It is quite ironic that after the French government was able to bring Barbie to justice. There was a reported effort by Bolivians to kidnap you and effect an exchange of Barbie for your return.

Debray: This is true but l am pleased that the plan was never executed.

Harwood: You missed the Spanish Civil War and you were too young to have joined the Resistance during World War II - you entered manhood through your Cuban and Bolivian adventures. You even returned to Bolivia in the Barbie episode. Is this struggle over?

Debray: I have had several lives and I don’t think that the last one is necessarily the best one. Maybe the first one, the Cuban one was the best one. But now in my present life I feel rather quiet and content because I discovered that I am not a Latin American. I discovered that I am a French European and I owe myself to my country and my culture.

Harwood: You risked your life many times in the past in the mountains of Bolivia with Che. Are you willing to risk your life now?

Debray: Yes I would. but that is too abstract a question now. If fundamentalists invade my country - but that I believe is remote - I will go into the mountains. I am ready l to leave on an adventure. but I don’t see one that is worthwhile, a vital one. I don`t feel that if I go to Guatemala and die in Guatemala I will have made a positive gesture. The Guatamalan people don`t need me . . . and maybe I don’t need them.

Harwood: Do you continue a relationship with Fidel Castro today?

Debray: I have some. yes. On personal terms.

Harwood: Do you reminisce about the old days? Do you discuss why he did not give greater support to you in the mountains?

Debray: I defend him when he is attacked and I attack him when he is too . . . of course we have many talks concerning that, but he discovered that I am profoundly European and French. and I discovered that he is profoundly Cuban and American. We are from two cultures. I don’t share anymore the internationalist feeling of belonging to the professional revolutionaries that can come one day to Shanghai and the next to Berlin.

Harwood: What did you discover about Fidel’s Cuban-Americanism vs your culture?

Debray: His Americanism is so strong. You mentioned baseball. There are so many elements of American identity that are shared by Castro and by Bush that are not shared by the French. There are many more links between Castro and Bush than between Castro and me.

Harwood: That is fascinating.

Debray: Their body language is the same.

Harwood: It is the same with the Nicaraguans? They have baseball too, but there doesn’t seem to be any reason for an immediate relationship there.

Debray: The Nicaraguans are more indigenous to Central America. Cuba was an American state - it was part of Florida.

Harwood: That is all encouraging, but Cuba and Castro still seem as far from Florida today as Albania. Do you see a rapprochement?

Debray: Ten or 15 years ago America could have adopted an intelligent policy toward Cuba, but now it is too late. There is more to it now since Castro may be the last Communist on earth. In Castro’s lifetime nothing serious will happen, but it is very important that efforts be made. America needs a symbol of evil. If you lose Cuba, what’s left?

Harwood: Among Americans, it seems that Barbara Walters has proven herself most adept in reaching Castro; have you ever considered playing an intermediary role between the United States and Cuba?

Debray: After 1981 we made an effort but Mr. Haig was completely hostile to any French negotiations with the Cubans. The Cubans were open, but it was clear that you have the Monroe Doctrine and you have an obsession with Cuba. And you can’t speak rationally on the subject. In 1981, we had a French-Mexican initiative concerning El Salvador. It was a declaration that could have led to negotiations, and we had serious North American connections. But it led to nothing. I would not hold any false hope. If you look at the map, you don’t see why you have to go to Paris from Miami to go to Havana. It looks more simple to take the plane from Miami to Havana. It’s only 80 miles.

Harwood: Somehow we are not speaking the same language.

Debray: You don’t need me. You don’t need the French to settle their differences with Cuba. Castro is a man who loves American people. He is aware of every election, of every election of a senator in North Dakota, every American movie and so on. He knows America better than I do.

Harwood: You mean that he has a satellite and watches American television?

Debray: Of course.

Harwood: Returning to the more theoretical issues, international struggles over technology seems to be determining the world political and economic agenda. The United States is fearful of the Japanese take-over of microchip and super-computer technology; and the Soviets are threatened by the Star Wars research and all that implies. The power of the information flow appears to be the determining political force. As a left-wing theorist, how do you perceive the nature of ideology in a technologically driven world? Has ideology receded completely?

Debray: This is a large question. But let me see if I can attack it, Technology for the French is not a major concern, it is a well developed country along these lines. There may be some concern about Germany’s economic power, but in general, France is in a good position. If you want to talk about the information revolution that’s something else. We have moved from representative democracy to a media driven democracy. The more a country becomes modern, the more it has to discover its historical roots. The whole American saga about technology and modernism sounds to me to be stupid. I am very skeptical about it all. I don’t think that it is sufficient to say that we don’t live in an ideological society. Ideology has evolved along with the needs of a consumerist state. We are no less ideological now than ever before. We are in a totally ideological society.

Harwood: If consumerism is a type of ideology on par with communism and capitalism, doesn’t that diminish somewhat the edge in an ideological struggle? Will couch potatoes, please forgive the American expression, ever go on strike?

Debray: It may seem to be a theoretical matter, but ideology exists when the individual is subordinate to certain values and equally there exists an ideological state when the ideology is subordinate to the needs of the individual and the man is never asked to sacrifice himself for the ideology. Of course the consumerist ideology does not have the same strength as an ideological society such as Khomeinfs. We can’t fight Khomeini because they are willing to die and we are not. Every ten years there is an announcement of the end of ideology. We had this just before 1968 in France and Raymond Aron announced the end of Communism and Socialism and at that point we had a revolution that was totally ideological. It was a cultural revolution based on ideas of Mao and Che Guevara. And even though those cultural icons do not exist today, I have this feeling that there remains a strong undercurrent of need for ideology. I do not share an apocalyptic view of the end of ideology in favor of the world of consumption.