GREAT MOMENTS

IN SPORTZ

Fear & Loathing @

The Kentucky Derby

IN SPORTZ

Fear & Loathing @

The Kentucky Derby

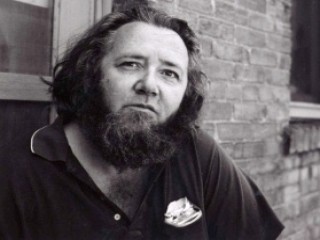

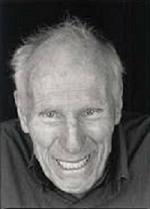

RALPH STEADMAN remembers meeting HUNTER S.THOMPSON

vs.

HUNTER S. THOMPSON remembers meeting RALPH STEADMAN

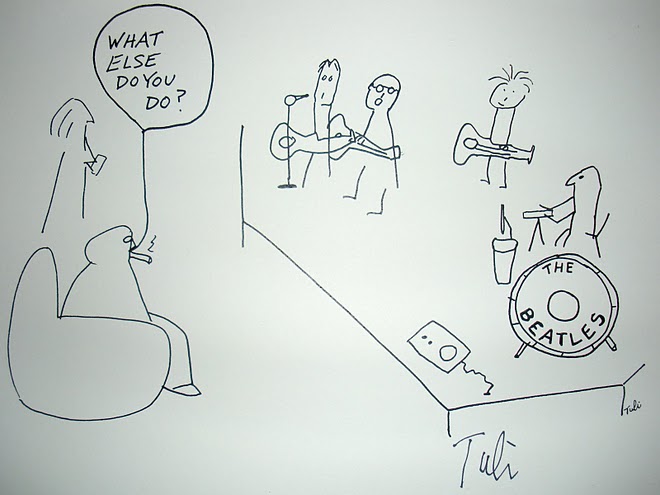

from Ralph Steadman’s THE JOKE IS OVER

Scanlan’s Monthly magazine, for those of you who missed those nine wild months of publishing history, was the brainchild of Warren Hinckle III, who scorched through three-quarters of a million dollars of borrowed money in the pitiless pursuit of truth – not least, the call to impeach Richard Nixon as early as 1970.

The magazine was named after a little known Nottingham pig farmer called Scanlan and it dedicated itself to maverick journalism and anything that seemed like a good idea at the time. Warren set about making sure everyone knew everything about anything that moved in America, from covert activities in high places to rats in a New York restaurant kitchen. His business partner was Sydney Zion, who later gained a reputation as the man who fingered psychiatrist, Daniel Ellsberg as the source of the ‘Pentagon Papers’, which had made public in The New York Times the US military’s account of activities during the Vietnam War.

They achieved their goal and made Nixon’s blacklist in record time. Unfortunately Warren’s excessive lifestyle and appetites outstripped the financial cornucopia that was there to begin with. After the ninth issue, the well dried up and the magazine sucked itself to death. When it happened (Hunter and I) were out on a limb, covering the America’s Cup for them. Not the best news to learn over a bad line to New York while asking for more funds.

Scanlan’s found me in Long Island in April 1970, not long after I had arrived from England to seek my particular vein of gold in the land of the screaming lifestyle. I was staying with my friend Dan Rattiner in the Hamptons. He ran – and, in fact, still runs – the local newspapers, Dan’s Paper and The East Hampton Other. I was just about to leave his place for the City, when I got a call from Scanlan’s Art Director, J.C. Suares. “We bin lookin’ all over for ya!” he growled with a pronounced Brooklyn accent. “How’d ya like to go to de Kentucky Derby and cover de race wid an ex-Hell’s Angel who just shaved his head, huh? His name is Hunter Thompson. He wants an artist to nail the decadent, depraved faces of the local establishment who meet there every year fer de Duurby. But he doesn’t want a photographer. He wants sometink weird and we’ve seen yer work, man!”

Scanlan’s 42nd Street offices were conveniently situated above a cozy bar serving Irish Guinness and flanked on either side by dark doorways, harboring drunks. J.C. Suares greeted me with some caution, treating me like a hired hit-man with a reputation which had arrived ahead of him. It was some time later that I learned that I had not been the first - get-Steadman-at-any-cost - choice. Hunter had originally suggested Pat Oliphant of the Denver Post. Oliphant, as it happened, was off to London to attend a cartoonists’ convention and had declined the invitation to be Hunter’s sidekick. I have to thank him or hate him for that, but he did save my first trip to America from being a total washout.

I was introduced to the editor, Donald Goddard, a kindly, shrewd man and an ex-foreign editor for the New York Times who had picked up a book of my collected cartoons in England called Still Life With Raspberry, the very week I left for America. Don explained, in a little more detail and with reserved reassurances, how interesting this job might prove to be. Being an Englishman, himself, he put my natural anxiety at ease as only another Englishman can.

On the way to the airport I stopped off at Don’s apartment where I met his wife, Natalie, a representative for Revlon, which was fortunate. You see, I had left my inks and colors in the taxi and was – as far as an artist is concerned, anyway – naked. Miraculously, Natalie had dozens of samples of Revlon lipstick and make-up preparations which solved the problem at a stroke. They were the ultimate in assimilated flesh color and, bizarrely, those Revlon samples were the birth of Gonzo art.

Finding Hunter, or, indeed, anyone who is not a bona fide, registered journalist covering the Kentucky Derby, is no easy matter and trying to explain my reasons for being there proved even more difficult, especially as I was under the impression that this was a bona fide trip anyway and I was a properly accredited press man. Why shouldn’t I think that? I assumed Scanlan’s was an established magazine. As it turned out, Scanlan’s had got me a hotel room cheap at a jerry-built complex called Browns! . Not able to locate Hunter at the hotel, though he had, in fact, booked in, I decided to take myself off to the track, eager to see for myself the color and excitement I had been led to expect. I carefully selected a sketch book, a couple of handy, felt-tip pens and a spy camera. I was imagining, in my naïve way, something like a New Orleans jazz carnival or a set from Carousel. My first impression, therefore, gave me a shock. Ugly people jockeyed and jostled for positions in an uncertain queue like a soup-kitchen line from the 1930’s.

I passed through a green, corrugated portal into a tunnel which led to the centre field where people with absolutely no important mission to fulfill sloshed around in a sea of empty beer cans, hot dog stands and obsolete form cards. Some people were camped out and well-ensconced with all the mod cons necessary for a comfortable three-day stint. This was carnival-centre and not an ounce of influence operated here. These were the Christians waiting to face the lions and the Romans were up there in the surrounding grandstands, making bets.

I retreated back the way I had come, looking around the back of the seat scaffolds and finally located the stairs leading to the Press Box. With a high charge of Welsh bewilderment, I talked myself inside, past a pleasant lady with a southern drawl and got myself a beer at the bar.

From where I stood I could see the course and the finishing posts. Press men were typing away and phoning editors and commentating through mikes to their radio stations. The races were in full swing and I felt heavy with a sense of inadequacy. I couldn’t type, I had no one to phone anything to, I knew nothing about racing and I couldn’t even locate the one man who could fill me in and make me feel that I was here for a purpose. It is a feeling I have experienced on many subsequent occasions where I have been shot into the middle of some strange place by some magazine or other which believes that all credentials are bullshit and that the mere mention of its name will send officials into paroxysms of reverence and respect. It’s understandable, as any magazine proprietor worth his salt will explain that the world is waiting with baited breath for his next issue. He must think like that or go under with plummeting circulation figures.

I had been watching someone chalk racing results on a blackboard while I finished my beer and was about to turn to get another when a voice like no other I had ever heard before cut into my thoughts, sinking its teeth into my brain. It was a cross between a slurred karate chop and gritty molasses.

I turned around and two eyes firmly socketed inside a bullet head were staring at the funny beard I was wearing on the end of my chin. Hunter was certainly not what I had been expecting. No time-worn leather, shining with old sump oil. No manic tattoo across a bare upper arm and certainly no hint of menace. No, this man had an impressive head cut from one piece of bone, the top part covered down to the eyes by a flimsy, white tight-brimmed sun hat. The top half of his body was draped in a hunting jacket of multi-colored patchwork and his bottom half wore slightly small, blue seersucker pants. The torso was prevented from crashing to the floor by a pair of huge, white plimsoles with fine red trim around the bulkheads. But they did seem in proportion as a foundation for what looked like a lot to support. Damn near six foot six of solid bone and meat, holding a beaten-up leather bag in one hand and a cigarette between the arthritic fingers of the other. His eyes gave away nothing of what he thought he was looking at in me – a ‘matted-haired geek with string warts’, as I found out later. Writers have a compulsion to tell all eventually, particularly journalistic ones whose only real reason for being a journalist anyway is to blast out the secrets they are entrusted with ‘off the record’ and surprise the world – or their editors.

We took a seat directly overlooking the race track and I relaxed with a beer in one hand and a sketchpad on my knee. Hunter had a notebook and made sporadic scribblings in red ink.

‘Do you bet?’ he asked. A race had just begun, so we chose a horse just for fun, to see how we made out, without spending a cent. The horse won, so we decided to try again for real. But my luck ran out and a modest amount of Scanlan’s expenses had disappeared within the hour. During that time we had sounded each other out and overcome our first impressions. We were getting along fine as he kept pointing out faces that, for him, represented the real Kentucky face. “That’s what we are here for,’ he would say. ‘Nail that and you have it.”

I had so far made no sketches, or notes, feeling far too intimidated to do either. But my head was buzzing with strange impressions. The last races were being run and there wasn’t much else to do around the track that would be helpful, so we decided to get back to the hotel, clean up and go into Louisville to eat. Hunter had hired a bright red whale of a car and had stored two buckets of beer, on ice, behind the front seats. We stopped off at a liquor store and bought a bottle of Wild Turkey Bourbon – a drink I had not been familiar with up to that point. It tasted good and went down even better, though compared to a good malt whisky it’s still a clumsy way to get drunk.

I was beginning to settle in, watching him drive. From the very first moment, I could tell he could handle a car with consummate skill. He was the sort of driver who could never be a passenger. One hand held the wheel, the other his cigarette holder and a beer can. Between his legs, or resting on the seat, he kept a tall glass full of ice and whisky. His consumption of each was carried out in nervous progressions. The cigarette holder, with lighted cigarette, was placed in the mouth, drawn on, taken out, and then, with the same hand holding the beer can and cigarette holder, beer was swilled. For a moment, the other hand came off the wheel which was held briefly with the free hand, the whiskey was swigged, put back down and then the driving hand was returned to the wheel. All done while turning corners or overtaking in the fast lane, the car following the direction of the front wheels, whatever the speed. It had to. Some divine intervention – or Wild Turkey — kept it on the road. Very occasionally I would hold the wheel at the magic point and the car would do as it was told. The clutch, brake, accelerator and Hunter’s deft footwork did the rest.

We needed to eat. I was in a slightly befuddled state by this time and the potent combination of watery beer and whiskey was bringing on a severe attack of drawing, as always happens when I start seeing unusual faces through a haze of controlled drinking. My body becomes a protective casing and lets me observe through the two keyholes on the front of my head.

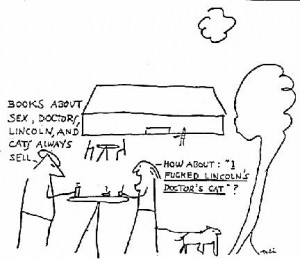

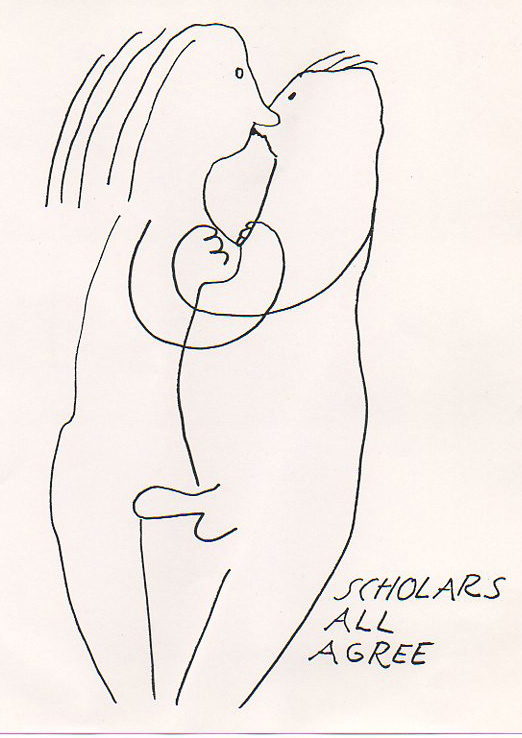

We were sitting in a restaurant, Hunter and me on one side of the table and Hunter’ brother Davison and his wife on the other, which prompted a drawing from me. Not a very kind drawing, as I recall, but it was only fun, anyway. However, you could see Davison was visibly shocked and it took me quite a while – many drawings later, in fact, to realize that Kentuckians and many other Americans for that matter, take things like that as a personal comment, and even in some cases, an insult, comparable to a smack in the mouth. Even Hunter was shocked and then horrified as I persisted in adding to the drawing, making it darker and darker and more hideous as lines covered lines. It is at a point like this that the drawing can take over and I am completely immersed in its development. It is no longer a sketch or merely a personal insult, but a battle between the drawing and my desire to mould and twist it. The drawing becomes more important than the subject. Other people were watching now. It was no longer a private affair.

Hunter fidgeted and made lame excuses for my preoccupation. “It’s a habit of his. This is nothing compared to what he did at the track this afternoon. Hideous things. We had to Mace people to escape. That’s enough Ralph. Stop it! Must be the Wild Turkey! He can’t hold his liquor! Sorry about this!” Hunter was fingering the Mace gun he had with him. He glanced around furtively. His brother’s face looked a little hurt and even annoyed. He didn’t say anything but he must have been restraining an impulse to retaliate. I was still unaware of the horrendous insult that this represented to these people and I had begun to draw the waiter. “I think we ought to go. Come on Ralph, cut this out or I won’t take responsibility for what happens!”

I remember the waiter bearing down on our table and Hunter on his feet; a black tube and a fine hissing sound. My eyes began to sting violently and I stumbled up, grabbing my sketch pad. I remember eyes staring from all directions, from dark corners of the restaurant, as we made for the door to the street. “Crazy fool!” Hunter screamed. I don’t remember any more.

I awoke on a bed, in my hotel room. There were pieces of sketchpad strewn around, covered in drunken scrawls of half-formed faces I vaguely remembered. I reached over and managed to grab one or two and gazed at them. The drawings told me I was out of control. They were the scribbles of some raving drunk. This would not do at all. But I keep everything – every piece of paper – or I sell it. But I keep it more often and if I find it by chance, I believe it to contain imagined properties which crave to be seen.

I have always found that whatever time I get to bed, even it it’s six in the morning, I’ll be up at eight, unable to succumb to the slovenly habit of lying in bed to catch up on sleep. Hunter was a different animal. He seemed to gain strength from rakish marathons. I am certain he learned the secret of maintaining a drug-wracked body from living out on the edge of lunacy and apparently normal discourse with everyday events. Whatever reaction he adopted towards a situation, whether it was giving a hell-raiser speech from the interior balconies of the Hyatt Regency Hotel in San Francisco or firing a magnum.44 at random into the night in front of strangers, he would always convince those around him that they were the ones who were mad, irrational or just plain dumb and he was behaving as a decent law-abiding citizen.

Today was Derby Day. I had taken breakfast and thought that, as it was now about nine-thirty, it would be a good plan to wake my friend who must have managed to get that extra hour’s sleep. I banged on his door and waited. Nothing. I banged again more emphatically and thought I heard a muffled cry from somewhere inside, like the sound a whale makes when searching for its mate. I banged again and called his name. A cry like twelve rhinos in mortal combat shook the flimsy walls and doors.

“Crazy English faggot. Go back where you belong. You faggots are all the same.” The door remained closed. I ignored the eccentric insults and tried again. “Come back in another two hours.” A mumble suggested that our conversation was at an end.

I went down to the lobby and observed for one hour with horrified fascination! Obesity was a common sight in most central and southern states. The culmination of years of hash browns and eggs sunny-side up, French fries, oily salads, pancakes with maple syrup and club sandwiches, washed down with sweet Coca Cola and blueberry milk shakes. It is no accident that men’s trousers are made in stretch-nylon synthetics, to accommodate their drooping paunches and elephantine legs and women’s dresses hang like marquees without tent pegs and guy ropes. The swamp-like humidity of a place like Kentucky brings rivers of sweat pouring over these undulating plains of wobbling flesh, dripping onto polished vinyl floors or down their socks into maroon and white sneakers.

I spent a while at the counter of the breakfast shop talking over one or two black coffees. Then made my way back to try Hunter again. Using the same approach, I banged fiercely on the door. I got the same response and a worse stream of abuse than the first time, but this time I wasn’t giving up.

A squinting dome of a head peered over the sheets, eyes contorted into scars as the fierce light bleached his features into a crumpled carnival mask. It was a ghastly sight. “Er, um, my God, what time is it?”

“Midday” I said.

“Goddam, why didn’t you wake me? We should be at the track!”

One hour later we were sitting in a roadside coffee shop-restaurant. Hunter had drunk a liter of orange juice, eaten about thirty different kinds of vitamin pills, two grapefruits, two club sandwiches, four bloody Marys and was just on his second Heineken with a scotch on the side. I have since come to suspect that he was a secret health freak who worked hard at it, devouring great gobs of health food and goat’s milk in vast quantities to build up his flailing insides to concert pitch before any bout with humanity. “Got to stoke up for the day ahead. It could get nasty. Aren’t you going to eat?”

“Well, I did actually. I had a lightly boiled egg and half a grapefruit a couple of hours ago. I’m fine.”

“My God! You won’t make it. This could be a day of ugliness. Horrible, horrible! People drinking and eating like pigs and vomiting everywhere. We’ll be sliding in the stuff before the week is out. And keep that damn thing out of sight.”

I was idly sketching a few of the late breakfast eaters as he talked. “Sorry,’ I said, ‘but I did come here to observe and draw.”

“Yes, but these people are primitive head-hunters. You’re liable to end up in a ditch, kicked to death by a horse.” I had begun to notice amongst all these stern warnings a hint of a twinkle in those tight eyes of his, as though he was secretly enjoying the possibilities that such a strange practice as mine might provoke. He had been used to working with photographers on other assignments and the detachment with which a photographer usually works gave him nothing against which he could spark. Here was something that could conceivably become a part of any story he worked on. An ongoing situation that could rear up and enter the scene at any unexpected moment, though I did not realize this at the time. There was something that was on his mind that he had not yet told me. He had no stomach for this story but he was going through the motions of appearing to be working on it. He had seen it all before and worse, he had been writing stories like these about sporting events and Chicago riots ad nauseam and right now it all seemed like a pointless way to go through life. What he had not yet let me know was that he had harbored a project since very early on that would help him to burn his own particular hole in life, but, in the process, would burn him too by the time he was forty. But here he was, large as life, at age 32, back in his home town, trying to crank up enthusiasm for some rich old vein of resentment he had felt a long time ago while still a youth, a reject from the powers that ran this God-awful place and he was saddled with some weirdly-bearded innocent abroad who was naïve beyond belief and who seemed unable to comprehend that any activity emitting hostile waves was bound to be interpreted as a fair provocation for physical violence by these people.

But maybe that was the reason for the twinkle in his eye. It was likely that at some point I would create some ghastly confrontation with an insulted cattle-rustler who would loom bigger than either of us, even if we both wore cowboy boots. That would be enough to start the juices flowing in anyone with a hint of journalistic flair. Perhaps the light of Gonzo was already beginning to streak across his tarnished mind while I was innocently attempting to contribute something tangible to this assignment. I doubt that it was a fully-formed idea from the very start; most good ideas rarely are, but this was surely the stuff of which stories can be made. The Kentucky Derby alone was certainly no reason to be here. It had been written about annually by armies of reporters since it had begun, but to find himself back on home ground with only a record of disillusionment in his soul, no prospects and an unfulfilled wish to have snuffed it at 30, there had to be something else. If you add to this the fact that at that very time he was experiencing severe family problems too – having to have your mother placed in an institution of care is severe. The stage was set for a weird chain of creative responses in the mind of anyone on that particular high wire. This was no ordinary homecoming. This was a do-or-die attempt to lay the ghost of years of rejection from the horse-rearing elite and the literati who sat in those privileged boxes overlooking the track and the unprivileged craven hordes who groveled around the centre-field where he had suffered as a boy.

“C’mon let’s go. We’d better get over there. You’ve got to see inside that clubhouse before the big race. Maybe you’ll see then just what you’re up against. Scanlan’s could get no passes so we’ll have to talk our way in.”

At the time, talking our way in didn’t seem as much of a problem as Hunter made out but maybe that was eased by the number of people he seemed to know around the Privilege Stand. Real, blue-glass rich, young who had either inherited their horde or started a second-hand car-mart ten years earlier. They were extremely friendly and had been made pliant by the mint juleps, another drink I had only just discovered. They had their own fridge-full under their seats. With their help we acquired the necessary ‘hail-fellow-hi-there – anyone who’s a friend of Jake’s is a friend of mine’ treatment.

The clubhouse, as far as I remember, was worse, much worse than I had expected. It was a mess. This was supposed to be a smart, horsy clubhouse, oozing with money and gentry, but what I saw had me skulking in corners. It was worse than the night I spent on Skid Row a month later, back in New York. My feet crunched broken glass on the floor. There seemed no difference between a telephone booth and a urinal; both were being used for the same purpose. Foul messages were scrawled in human excrement on the walls and bull-necked men in what had once been white, but now were smeared and stained, seersucker suits, were doing awful things to younger but equally depraved men around every dark corner. The place reminded me of a cowshed that hadn’t been cleaned for fifteen years. Resolutely, I stayed there, but really only because of my own desperately befuddled and drunken state. Somehow I knew I had to look and observe. It was my job. What was I being paid for? I was lucky to be here. Lots of people would give their drawing arm to be able to see the actual Kentucky Derby, which was now hardly an hour away. Hunter understood and was watching me as much as he was watching the scene before us.

A bottle hit the wall and its contents spewed down in a bubbling stream to the floor. It is strange how one seems to gain drunkard’s immunity from personal injury when completely plastered and by now we had swilled more than we cared to think about.

Something spattered the page I was drawing on and, as I moved to wipe it away, I realized too late that it was somebody’s vomit. A ghastly-looking gargoyle-faced horse-dealer had hurled from about five feet away and the pressure-driven contents of his insides had miraculously missed me and caught the elevated plane of my sketch pad sufficiently to splatter down the page in an array of color which would have been a wonderful effect artistically, if it had not been for the evil smell.

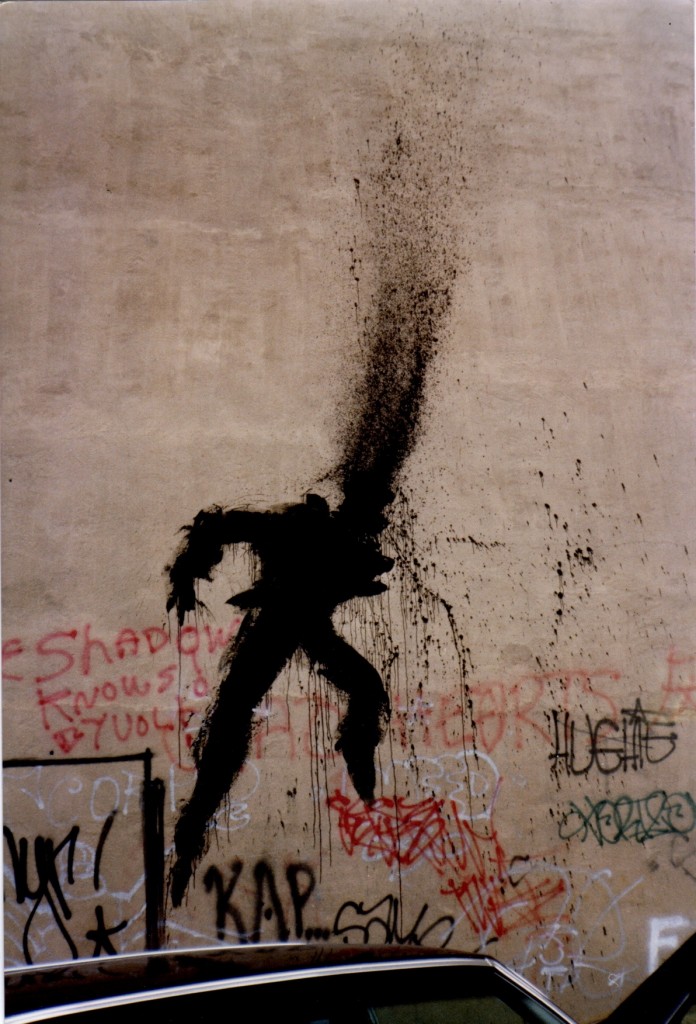

During the worst days of the Weimar Republic, when Hitler was rising faster than a bull on heat, George Grosz, the savage satirical painter had used human shit as a violent method of coloring his drawings. It is a shade of brown like no other and its use makes an ultimate statement about the subject. Its organic nature lends a powerful presence to the image and no one misses the point.

‘Seen enough?’ asked Hunter, pushing me hastily towards an exit that led out to the club enclosure. “Only another half-hour to the big race. If we don’t catch the inner field now, we’ll miss it.”

Black faces talking bets. Tripping over hot dogs half-eaten in piles of Coke and beer cans, bodies in a final state of consciousness before dying, or just sleeping. Ripped T-shirts and odd-shaped hats, home-painted to say their piece; political or just plain saucy. While the scene was as wild here as it had been in the club house, it had a warmer, more human face, more color and happiness and gay abandon – the difference in atmosphere between Hogarth’s Gin Lane and Beer Street. One harrowed and death-like, the other bloated with booze but animal-healthy.

It was then that I conceived the idea to turn and face the crowd the moment the race started. So what, I thought, I hadn’t come to see the race anyhow. It was the people and what better than to observe them utterly engrossed in their hopes out there on the track? What stories their faces would tell. I would photograph them constantly throughout the race and get myself a group of pictures that would surely reveal the true Kentucky face.

Nobody noticed me facing the wrong way, but it was an unnerving experience. I was experiencing the full weight of an actor’s-eye view of this energized audience whose emotions individually and collectively pulsed forward towards the track as the moment arrived, one second before the race.

I stood my ground, though my impulse was to turn the same way as everyone else. “Hey boy! You’re facing the wrong way, boy!”

This warranted more than a camera shot. It was drawing time again and out came my sketchpad.

“Hey Steadman, hold it!” Hunter was already anticipating trouble. “Put your book away.”

“But he called me ‘boy’!” I protested.

“In this town they call everyone under eighty ‘boy’.”

I succumbed to my natural fear of physical violence and put my sketchbook away. “ I’ll take his picture instead and do the bugger later. He’s the type I think you are looking for – the Kentucky face.”

“I’m looking for something worse than that. The nearest you’ve come to it so far was the picture of my brother and that worries me. My mother is Dorothy Lamour compared to that twisted pig-fucker you were about to tangle with.”

I was watching the man’s binoculars dangle around his belly. “Hold it sir! Photographer for the Courier, Journal and Times. Wanna be in pre-int dontcha?” Snap! ‘Got you, you bastard!’ I thought, keeping it to myself.

The other spectators were too engrossed in the race to bother about some drunken photographer snapping like a demented tourist. It was good publicity, anyway. Might end up on the Louisville Courier front page – friends of the winning horse. Another Asshole!

Who would have thought that I was after the gristle, the blood-throbbing veins, poisoned exquisitely by endless self-indulgence, mint juleps and bourbon? Hide, anyway, behind the dark shades, you predatory piece of raw blubber. Is that your wife by your side or a cake of wrinkled make up, waiting for its owner to return. It was moving with heaving animation, glowing with rouge – an ocean of rolling surf breaking on wet sand, cutting sharp moments of wrinkled sweat into an undulating mask beneath cantilevered shades that sparkled with diamante rims. Some of the pink dinosaurs were slightly younger, softer versions, daughters cleft from pedigree stock to preserve the line. Interbreeding was rife, no doubt, and new blood would only be injected by healthy young rednecks whose ticket to these inner circles came through the stables where they would eventually become trainers and lay an owner’s daughter as soon as was decently possible. The older versions wore light, bright, summer coats, either plain white with acid, julep-green edging or outrageous sack-shaped coats in checks as broad as a freeway.

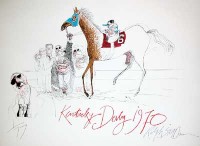

The race was now getting a frenzied response as Dust Commander began to make the running. Bangles and jewels rattled on suntanned, wobbling flesh and even the pillar men in suits were now on tip-toe, creased skin under double chins stretched to the limit, into long furrows that curved down into tight collars. Mouths opened and closed and veins pulsed in unison on stretched necks as the frenzy reached its climax. Sweat rolled down the flesh-furrows into their collars. One or two slumped back as their horses failed, but the mass hysteria rose to a final orgasmic shriek, at last bubbling over into whoops of joy, hugging and back-slapping. I turned to face the track again, but it was all over. That was it. The 1970 Kentucky Derby won by Dust Commander with a lead of five lengths – the biggest winning margin since 1946 when Triple Crown Champion, Assault, won the Derby by eight lengths.

The next morning I suggested, “it’s time I was thinking of getting back to New York. Let’s have a meal somewhere and I can phone the airline for plane times.” I hugged myself, trying to stop shaking. “I need a drink.”

“You need lynching!” Hunter was not yet up but was making an effort to rouse himself. As always, I had awakened at eight on an unknown day and had gone through my Boy Scout routine to freshen up. “You’ve upset my friends and I haven’t written a goddamn word. I’ve been too busy looking after you.” He was still in bed. “Your work is done. I can never come back here again. Why don’t you go back where you came from and let me sleep. Go and plague someone else with your problems.”

We laid the drawings out two hours later as we ate capsized omelettes and drank stewed coffee. I was feeling bad now and Hunter was preoccupied, worried. “This whole thing will probably finish me as a writer. I have no story.”

“Well I know we got a bit pissed and let things slip a bit but there’s lots of color. Lots happened.”

“Holy Shit! You scumbag! This is Kentucky, not Skid Row. I love these people. They are my friends and you treated them like scum.”

“Well I’m sorry. I just tried to be objective. I’m here to find something worth publishing. It wouldn’t do to go back with picturesque landscapes of Kentucky and elegant horses. You showed me the depravity. You must remember, I’ve suffered culture shock. It’s not easy to stay normal. I’m sorry. I’m more worried about your story, because without it, my drawings are worthless. Without the words they lack authenticity.”

“Fuck the story! At this point there is no story. I grew up here. I went away and I came back. You appeared on the scene with this stuff like a traveling priest peddling twisted morality.”

“I’m just trying to do my job.”

“You miserable Golom!!! That’s what Hitler said. Shit!” Hunter brought his fist down on the omelet set out for him in the coffee bar we had gone to. I wiped feebly at the scrambled substance sticking to my already crumpled sports jacket in an attempt to lessen the shocking effect this would have on my alarming countenance. I had only been there a week.

The few patrons who, for masochistic reasons known only to themselves, had ventured into this World War II concrete tank-trap of a coffee shop, were feverishly finishing their respective beverages as they fumbled for ten dollar bills or anything that would amply cover their tabs without having to wait around to pay at the desk. The scene was getting ugly and ten dollars was, I expect, a cheap price to pay for the preservation of the clothes they were trying to sneak out in and anyway, the cash till and the proprietor, himself, were covered in the stuff, so getting change would have been a messy business and, perhaps, a little weird.

I eyed the proprietor nervously, expecting him to reach for the phone – It was only the excruciating stinging in my eyes that snapped me out of my daydream – a defense mechanism against a situation I couldn’t handle. I heard Hunter raving on as I stumbled about helplessly trying to retrieve my drawings and baggage. “I’ve wanted a worthy cause to try out this chemical billy properly on all week and now I’ve found it, you scumsucking geek! That’s it. Chew on that for a while.”

I heard a quick hiss from the spray can Hunter was brandishing. He had Maced me again! I choked and ripped at my shirt in an attempt to stop the stuff burning my skin. My flailing hands caught something – a beer can – and I tilted the contents over my face and chest to relieve the suffocating pain. I screamed with relief but the pain returned immediately.

A hand gripped my coat and shoved me forward violently. The clammy heat of the midday sun intensified the burning and the hot tar of the car lot outside scalded the palms of my hands. “My drawings – where are my drawings. I can’t see!”

“I’ve got your drawings, you worthless faggot. Get in the car – you’re causing a scene. Do you want to end up in jail too?” There was no sympathy in Hunter’s voice now. It was as cold and hard as a municipal sewer pipe. I crawled into the open door and grabbed wildly for the ice bucket I knew was behind Hunter’s seat, splashing the still cool water over me with a cupped hand.

“Mind the seats, goddamn it. This is a rental car.”

The cool water eased the searing sting momentarily and I felt the car roar forward as Hunter angrily threw it onto the freeway. “I’m taking you to the airport, though God knows why I should try and save your wretched little ass. If you weren’t a weird stranger I’d let them hurl you in jail but I don’t need you on my conscience.”

The front of my shirt was wet and reeked of vomit, but it couldn’t be mine because I could not remember being sick. Hunter was driving angrily, cursing the traffic as well as me. I saw my face in the rear-view driving mirror. My stinging eyes looked like crushed pomegranates and I remember having a coughing fit. I was not well.

Hunter skidded violently to a stop in front of the terminal. He reached over and opened my door for me and he threw such a barrage of verbal abuse at me, I knew I had really upset him. But I didn’t know why, since I was the injured party. ‘Now bug off, you worthless faggot!’ he snarled, ‘You twisted pigfucker!!’ He laughed maniacally at the sight of me. Then still half-laughing he gurgled: ‘If I weren’t so sick I’d kick your ass all the way to Bowling Green – you scum-sucking foreign geek. Mace is too good for you. We can do without your kind in Kentucky. Now get your bags and get out, and take your rotten drawings with you!’ Then, I watched him go, his wheels squealing on the tarmac.

That was a successful trip, I thought. I fumbled to find my sunglasses to cover my eyes and walked up to the check-in desk.

I cleaned up in the aircraft toilet during the flight and on arrival in New York made my way straight to Scanlan’s offices to lodge a complaint. However, the offices were closed and I took a beer in the bar downstairs while I wrote a note to accompany the drawings, explaining the oily stains from the omelet and the wreak of the cosmetics I had used to color them. I made my way back to the flat I was staying at in West 11th Street in Greenwich village and collapsed onto the bed.

I was awoken from my deep torpor by the phone. It was Warren Hinkle III. “Hey, Steadman, what’d you do to Hunter? He says he can’t write and he’s blaming you for arresting his creative flow. Didn’t you two hit it off?”

““Got on like a house on fire,” I said, “but he seemed to have personal problems to overcome. Home town, past memories, meeting old friends, mother, and so on. I’m sure he’ll produce something soon.” I’ll be along to the office just as soon as I finish this horse drawing.” I rang off and stood silently for a minute or so, staring blankly at the shaking right hand I had raised to wipe the sweat from my brow. It was early May and the heat was beginning to build up in the city.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Before I left New York a month later, I asked Warren Hinckle III out of curiosity about my Kentucky drawings. I rarely part with my work and I certainly would not have willingly parted with those ones. I was assured by JC Suares that they had been taken by Warren, personally, to the printers in San Francisco on one of his twice weekly east-west coast flights with Sidney Zion – ‘for safety’, he added. So I asked Warren where my drawings were.

“How the fuck should I know, Steadman? was his brusque reply. “Maybe someone wiped their ass on ‘em!” he twinkled out of his one good eye.

I never did find out, but, wherever they are, they still belong to me…..

**********

|

The writing and drawings that make up the legendary 1971 Scanlan’s article The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent And Depraved elevated Hunter Thompson and Ralph Steadman into overnight superstars, and was the forerunner for the books Fear & Loathing In Las Vegas and Fear & Loathing On The Campaign Trail. A longer version of Ralph’s story about the beginning of this unique creative partnership can be found in The Joke Is Over, his memoir about their strange 30+year relationship. |

And now here’s Hunter’s version of their first meeting:

The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved

by Hunter S. Thompson

The following essay was originally published in Scanlan’s Monthly, vol. 1, no. 4, June 1970.

The text of this essay was taken from the book The Great Shark Hunt, Gonzo Papers, Vol. 1, Strange Tales from a Strange Time by Hunter S. Thompson

I got off the plane around midnight and no one spoke as I crossed the dark runway to the terminal. The air was thick and hot, like wandering into a steam bath. Inside, people hugged each other and shook hands…big grins and a whoop here and there: “By God! You old bastard! Good to see you, boy! Damn good…and I mean it!”

In the air-conditioned lounge I met a man from Houston who said his name was something or other–”but just call me Jimbo”–and he was here to get it on. “I’m ready for anything, by God! Anything at all. Yeah, what are you drinkin?” I ordered a Margarita with ice, but he wouldn’t hear of it: “Naw, naw…what the hell kind of drink is that for Kentucky Derby time? What’s wrong with you, boy?” He grinned and winked at the bartender. “Goddam, we gotta educate this boy. Get him some good whiskey…”

I shrugged. “Okay, a double Old Fitz on ice.” Jimbo nodded his approval.

“Look.” He tapped me on the arm to make sure I was listening. “I know this Derby crowd, I come here every year, and let me tell you one thing I’ve learned–this is no town to be giving people the impression you’re some kind of faggot. Not in public, anyway. Shit, they’ll roll you in a minute, knock you in the head and take every goddam cent you have.”I thanked him and fitted a Marlboro into my cigarette holder. “Say,” he said, “you look like you might be in the horse business…am I right?”

“No,” I said. “I’m a photographer.”

“Oh yeah?” He eyed my ragged leather bag with new interest. “Is that what you got there–cameras? Who you work for?”

“Playboy,” I said.

He laughed. “Well, goddam! What are you gonna take pictures of–nekkid horses? Haw! I guess you’ll be workin’ pretty hard when they run the Kentucky Oaks. That’s a race just for fillies.” He was laughing wildly. “Hell yes! And they’ll all be nekkid too!”

I shook my head and said nothing; just stared at him for a moment, trying to look grim. “There’s going to be trouble,” I said. “My assignment is to take pictures of the riot.”

“What riot?”

I hesitated, twirling the ice in my drink. “At the track. On Derby Day. The Black Panthers.” I stared at him again. “Don’t you read the newspapers?”

The grin on his face had collapsed. “What the hell are you talkin’ about?”

“Well…maybe I shouldn’t be telling you…” I shrugged. “But hell, everybody else seems to know. The cops and the National Guard have been getting ready for six weeks. They have 20,000 troops on alert at FortKnox. They’ve warned us–all the press and photographers–to wear helmets and special vests like flak jackets. We were told to expect shooting…”

“No!” he shouted; his hands flew up and hovered momentarily between us, as if to ward off the words he was hearing. Then he whacked his fist on the bar. “Those sons of bitches! God Almighty! The KentuckyDerby!” He kept shaking his head. “No! Jesus! That’s almost too bad to believe!” Now he seemed to be sagging on the stool, and when he looked up his eyes were misty. “Why? Why here? Don’t they respect anything?“

I shrugged again. “It’s not just the Panthers. The FBI says busloads of white crazies are coming in from all over the country–to mix with the crowd and attack all at once, from every direction. They’ll be dressed like everybody else. You know–coats and ties and all that. But when the trouble starts…well, that’s why the cops are so worried.”

He sat for a moment, looking hurt and confused and not quite able to digest all this terrible news. Then he cried out: “Oh…Jesus! What in the name of God is happening in this country? Where can you get away from it?”

“Not here,” I said, picking up my bag. “Thanks for the drink…and good luck.”

He grabbed my arm, urging me to have another, but I said I was overdue at the Press Club and hustled off to get my act together for the awful spectacle. At the airport newsstand I picked up a Courier-Journal and scanned the front page headlines: “Nixon Sends GI’s into Cambodia to Hit Reds”… “B-52’s Raid, then 20,000 GI’s Advance 20 Miles”…”4,000 U.S. Troops Deployed Near Yale as Tension Grows Over Panther Protest.” At the bottom of the page was a photo of Diane Crump, soon to become the first woman jockey ever to ride in the KentuckyDerby. The photographer had snapped her “stopping in the barn area to fondle her mount, Fathom.” The rest of the paper was spotted with ugly war news and stories of “student unrest.” There was no mention of any trouble brewing at university in Ohio called KentState.

I went to the Hertz desk to pick up my car, but the moon-faced young swinger in charge said they didn’t have any. “You can’t rent one anywhere,” he assured me. “Our Derby reservations have been booked for six weeks.” I explained that my agent had confirmed a white Chrysler convertible for me that very afternoon but he shook his head. “Maybe we’ll have a cancellation. Where are you staying?”

I shrugged. “Where’s the Texas crowd staying? I want to be with my people.”

He sighed. “My friend, you’re in trouble. This town is flat full. Always is, for the Derby.”

I leaned closer to him, half-whispering: “Look, I’m from Playboy. How would you like a job?”

He backed off quickly. “What? Come on, now. What kind of a job?”

“Never mind,” I said. “You just blew it.” I swept my bag off the counter and went to find a cab. The bag is a valuable prop in this kind of work; mine has a lot of baggage tags on it–SF, LA, NY, Lima, Rome, Bangkok, that sort of thing–and the most prominent tag of all is a very official, plastic-coated thing that says “Photog. Playboy Mag.” I bought it from a pimp in Vail, Colorado, and he told me how to use it.“Never mention Playboy until you’re sure they’ve seen this thing first,” he said. “Then, when you see them notice it, that’s the time to strike. They’ll go belly up ever time. This thing is magic, I tell you. Pure magic.”

Well…maybe so. I’d used it on the poor geek in the bar, and now humming along in a Yellow Cab toward town, I felt a little guilty about jangling the poor bugger’s brains with that evil fantasy. But what the hell? Anybody who wanders around the world saying, “Hell yes, I’m from Texas,” deserves whatever happens to him. And he had, after all, come here once again to make a nineteenth-century ass of himself in the midst of some jaded, atavistic freakout with nothing to recommend it except a very saleable “tradition.” Early in our chat, Jimbo had told me that he hadn’t missed a Derby since 1954. “The little lady won’t come anymore,” he said. “She grits her teeth and turns me loose for this one. And when I say ‘loose’ I do mean loose! I toss ten-dollar bills around like they were goin’ out of style! Horses, whiskey, women…shit, there’s women in this town that’ll do anything for money.”

Why not? Money is a good thing to have in these twisted times. Even Richard Nixon is hungry for it. Only a few days before the Derby he said, “If I had any money I’d invest it in the stock market.” And the market, meanwhile, continued its grim slide.

**********

The next day was heavy. With only thirty hours until post time I had no press credentials and–according to the sports editor of the Louisville Courier-Journal–no hope at all of getting any. Worse, I needed two sets: one for myself and another for Ralph Steadman, the English illustrator who was coming from London to do some Derby drawings. All I knew about him was that this was his first visit to the United States. And the more I pondered the fact, the more it gave me fear. How would he bear up under the heinous culture shock of being lifted out of London and plunged into the drunken mob scene at the Kentucky Derby? There was no way of knowing. Hopefully, he would arrive at least a day or so ahead, and give himself time to get acclimated. Maybe a few hours of peaceful sightseeing in the Bluegrass country around Lexington. My plan was to pick him up at the airport in the huge Pontiac Ballbuster I’d rented from a used-car salesman name Colonel Quick, then whisk him off to some peaceful setting that might remind him of England.

Colonel Quick had solved the car problem, and money (four times the normal rate) had bought two rooms in a scumbox on the outskirts of town. The only other kink was the task of convincing the moguls at Churchill Downs that Scanlan’s was such a prestigious sporting journal that common sense compelled them to give us two sets of the best press tickets. This was not easily done. My first call to the publicity office resulted in total failure. The press handler was shocked at the idea that anyone would be stupid enough to apply for press credentials two days before the Derby. “Hell, you can’t be serious,” he said. “The deadline was two months ago. The press box is full; there’s no more room…and what the hell is Scanlan’s Monthly anyway?”I uttered a painful groan. “Didn’t the London office call you? They’re flying an artist over to do the paintings. Steadman. He’s Irish. I think. Very famous over there. Yes. I just got in from the Coast. The San Francisco office told me we were all set.”

He seemed interested, and even sympathetic, but there was nothing he could do. I flattered him with more gibberish, and finally he offered a compromise: he could get us two passes to the clubhouse grounds but the clubhouse itself and especially the press box were out of the question.

“That sounds a little weird,” I said. “It’s unacceptable. We must have access tp everything. All of it. The spectacle, the people, the pageantry and certainly the race. You don’t think we came all this way to watch the damn thing on television, do you? One way or another we’ll get inside. Maybe we’ll have to bribe a guard–or even Mace somebody.” (I had picked up a spray can of Mace in a downtown drugstore for $5.98 and suddenly, in the midst of that phone talk, I was struck by the hideous possibilities of using it out at the track. Macing ushers at the narrow gates to the clubhouse inner sanctum, then slipping quickly inside, firing a huge load of Mace into the governor’s box, just as the race starts. Or Macing helpless drunks in the clubhouse restroom, for their own good…)

By noon on Friday I was still without press credentials and still unable to locate Steadman. For all I knew he’d changed his mind and gone back to London. Finally, after giving up on Steadman and trying unsuccessfully to reach my man in the press office, I decided my only hope for credentials was to go out to the track and confront the man in person, with no warning–demanding only one pass now, instead of two, and talking very fast with a strange lilt in my voice, like a man trying hard to control some inner frenzy. On the way out, I stopped at the motel desk to cash a check. Then, as a useless afterthought, I asked if by any wild chance a Mr. Steadman had checked in.

The lady on the desk was about fifty years old and very peculiar-looking; when I mentioned Steadman’s name she nodded, without looking up from whatever she was writing, and said in a low voice, “You bet he did.” Then she favored me with a big smile. “Yes, indeed. Mr. Steadman just left for the racetrack. Is he a friend of yours?”

I shook my head. “I’m supposed to be working with him, but I don’t even know what he looks like. Now, goddammit, I’ll have to find him in the mob at the track.”

She chuckled. “You won’t have any trouble finding him. You could pick that man out of any crowd.”

“Why?” I asked. “What’s wrong with him? What does he look like?”

“Well…” she said, still grinning, “he’s the funniest looking thing I’ve seen in a long time. He has this…ah…this growth all over his face. As a matter of fact it’s all over his head.”

She nodded. “You’ll know him when you see him; don’t worry about that.”

Creeping Jesus, I thought. That screws the press credentials. I had a vision of some nerve-rattling geek all covered with matted hair and string-warts showing up in the press office and demanding Scanlan’s press packet. Well…what the hell? We could always load up on acid and spend the day roaming around the clubhouse grounds with bit sketch pads, laughing hysterically at the natives and swilling mint juleps so the cops wouldn’t think we’re abnormal. Perhaps even make the act pay; set up an easel with a big sign saying, “Let a Foreign Artist Paint Your Portrait, $10 Each. Do It NOW!”

**********

I took the expressway out to the track, driving very fast and jumping the monster car back and forth between lanes, driving with a beer in one hand and my mind so muddled that I almost crushed a Volkswagen full of nuns when I swerved to catch the right exit. There was a slim chance, I thought, that I might be able to catch the ugly Britisher before he checked in.But Steadman was already in the press box when I got there, a bearded young Englishman wearing a tweed coat and RAF sunglasses. There was nothing particularly odd about him. No facial veins or clumps of bristly warts. I told him about the motel woman’s description and he seemed puzzled. “Don’t let it bother you,” I said. “Just keep in mind for the next few days that we’re in Louisville, Kentucky. Not London. Not even New York. This is a weird place. You’re lucky that mental defective at the motel didn’t jerk a pistol out of the cash register and blow a big hole in you.” I laughed, but he looked worried.

“Just pretend you’re visiting a huge outdoor loony bin,” I said. “If the inmates get out of control we’ll soak them down with Mace.” I showed him the can of “Chemical Billy,” resisting the urge to fire it across the room at a rat-faced man typing diligently in the Associated Press section. We were standing at the bar, sipping the management’s Scotch and congratulating each other on our sudden, unexplained luck in picking up two sets of fine press credentials. The lady at the desk had been very friendly to him, he said. “I just told her my name and she gave me the whole works.

”By midafternoon we had everything under control. We had seats looking down on the finish line, color TV and a free bar in the press room, and a selection of passes that would take us anywhere from the clubhouse roof to the jockey room. The only thing we lacked was unlimited access to the clubhouse inner sanctum in sections “F&G”…and I felt we needed that, to see the whiskey gentry in action. The governor, a swinish neo-Nazi hack named Louis Nunn, would be in “G,” along with Barry Goldwater and Colonel Sanders. I felt we’d be legal in a box in “G” where we could rest and sip juleps, soak up a bit of atmosphere and the Derby’s special vibrations.

The bars and dining rooms are also in “F&G,” and the clubhouse bars on Derby Day are a very special kind of scene. Along with the politicians, society belles and local captains of commerce, every half-mad dingbat who ever had any pretensions to anything at all within five hundred miles of Louisville will show up there to get strutting drunk and slap a lot of backs and generally make himself obvious. The Paddock bar is probably the best place in the track to sit and watch faces. Nobody minds being stared at; that’s what they’re in there for. Some people spend most of their time in the Paddock; they can hunker down at one of the many wooden tables, lean back in a comfortable chair and watch the ever-changing odds flash up and down on the big tote board outside the window. Black waiters in white serving jackets move through the crowd with trays of drinks, while the experts ponder their racing forms and the hunch bettors pick lucky numbers or scan the lineup for right-sounding names. There is a constant flow of traffic to and from the pari-mutuel windows outside in the wooden corridors. Then, as post time nears, the crowd thins out as people go back to their boxes.

Clearly, we were going to have to figure out some way to spend more time in the clubhouse tomorrow. But the “walkaround” press passes to F&G were only good for thirty minutes at a time, presumably to allow the newspaper types to rush in and out for photos or quick interviews, but to prevent drifters like Steadman and me from spending all day in the clubhouse, harassing the gentry and rifling the odd handbag or two while cruising around the boxes. Or Macing the governor. The time limit was no problem on Friday, but on Derby Day the walkaround passes would be in heavy demand. And since it took about ten minutes to get from the press box to the Paddock, and ten more minutes to get back, that didn’t leave much time for serious people-watching. And unlike most of the others in the press box, we didn’t give a hoot in hell what was happening on the track. We had come there to watch the real beasts perform.

**********

Later Friday afternoon, we went out on the balcony of the press box and I tried to describe the difference between what we were seeing today and what would be happening tomorrow. This was the first time I’d been to a Derby in ten years, but before that, when I lived in Louisville, I used to go every year. Now, looking down from the press box, I pointed to the huge grassy meadow enclosed by the track. “That whole thing,” I said, “will be jammed with people; fifty thousand or so, and most of them staggering drunk. It’s a fantastic scene–thousands of people fainting, crying, copulating, trampling each other and fighting with broken whiskey bottles. We’ll have to spend some time out there, but it’s hard to move around, too many bodies.”

“Is it safe out there?” Will we ever come back?”

“Sure,” I said. “We’ll just have to be careful not to step on anybody’s stomach and start a fight.” I shrugged. “Hell, this clubhouse scene right below us will be almost as bad as the infield. Thousands of raving, stumbling drunks, getting angrier and angrier as they lose more and more money. By midafternoon they’ll be guzzling mint juleps with both hands and vomitting on each other between races. The whole place will be jammed with bodies, shoulder to shoulder. It’s hard to move around. The aisles will be slick with vomit; people falling down and grabbing at your legs to keep from being stomped. Drunks pissing on themselves in the betting lines. Dropping handfuls of money and fighting to stoop over and pick it up.”

He looked so nervous that I laughed. “I’m just kidding,” I said. “Don’t worry. At the first hint of trouble I’ll start pumping this ‘Chemical Billy’ into the crowd.”

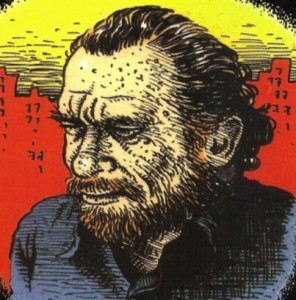

He had done a few good sketches, but so far we hadn’t seen that special kind of face that I felt we would need for a lead drawing. It was a face I’d seen a thousand times at every Derby I’d ever been to. I saw it, in my head, as the mask of the whiskey gentry–a pretentious mix of booze, failed dreams and a terminal identity crisis; the inevitable result of too much inbreeding in a closed and ignorant culture. One of the key genetic rules in breeding dogs, horses or any other kind of thoroughbred is that close inbreeding tends to magnify the weak points in a bloodline as well as the strong points. In horse breeding, for instance, there is a definite risk in breeding two fast horses who are both a little crazy. The offspring will likely be very fast and also very crazy. So the trick in breeding thoroughbreds is to retain the good traits and filter out the bad. But the breeding of humans is not so wisely supervised, particularly in a narrow Southern society where the closest kind of inbreeding is not only stylish and acceptable, but far more convenient–to the parents–than setting their offspring free to find their own mates, for their own reasons and in their own ways. (”Goddam, did you hear about Smitty’s daughter? She went crazy in Boston last week and married a nigger!”)

So the face I was trying to find in Churchill Downs that weekend was a symbol, in my own mind, of the whole doomed atavistic culture that makes the Kentucky Derby what it is.

On our way back to the motel after Friday’s races I warned Steadman about some of the other problems we’d have to cope with. Neither of us had brought any strange illegal drugs, so we would have to get by on booze. “You should keep in mind,” I said, “that almost everybody you talk to from now on will be drunk. People who seem very pleasant at first might suddenly swing at you for no reason at all.” He nodded, staring straight ahead. He seemed to be getting a little numb and I tried to cheer him up by inviting to dinner that night, with my brother.

Back at the motel we talked for awhile about America, the South, England–just relaxing a bit before dinner. There was no way either of us could have known, at the time, that it would be the last normal conversation we would have. From that point on, the weekend became a vicious, drunken nightmare. We both went completely to pieces. The main problem was my prior attachment to Louisville, which naturally led to meetings with old friends, relatives, etc., many of whom were in the process of falling apart, going mad, plotting divorces, cracking up under the strain of terrible debts or recovering from bad accidents. Right in the middle of the whole frenzied Derby action, a member of my own family had to be institutionalized. This added a certain amount of strain to the situation, and since poor Steadman had no choice but to take whatever came his way, he was subjected to shock after shock.

Another problem was his habit of sketching people he met in the various social situations I dragged him into–then giving them the sketches. The results were always unfortunate. I warned him several times about letting the subjects see his foul renderings, but for some perverse reason he kept doing it. Consequently, he was regarded with fear and loathing by nearly everyone who’d seen or even heard about his work. Ho couldn’t understand it. “It’s sort of a joke,” he kept saying. “Why, in England it’s quite normal. People don’t take offense. They understand that I’m just putting them on a bit.”

“Fuck England,” I said. “This is Middle America. These people regard what you’re doing to them as a brutal, bilious insult. Look what happened last night. I thought my brother was going to tear your head off.”

Steadman shook his head sadly. “But I liked him. He struck me as a very decent, straightforward sort.”

“Look, Ralph,” I said. “Let’s not kid ourselves. That was a very horrible drawing you gave him. It was the face of a monster. It got on his nerves very badly.” I shrugged. “Why in hell do you think we left the restaurant so fast?”

“I thought it was because of the Mace,” he said.

“What Mace?”

He grinned. “When you shot it at the headwaiter, don’t you remember?”

“Hell, that was nothing,” I said. “I missed him…and we were leaving, anyway.”

“But it got all over us,” he said. “The room was full of that damn gas. Your brother was sneezing was and his wife was crying. My eyes hurt for two hours. I couldn’t see to draw when we got back to the motel.”

“That’s right,” I said. “The stuff got on her leg, didn’t it?”

“She was angry,” he said.

“Yeah…well, okay…Let’s just figure we fucked up about equally on that one,” I said. “But from now on let’s try to be careful when we’re around people I know. You won’t sketch them and I won’t Mace them. We’ll just try to relax and get drunk.”

“Right,” he said. “We’ll go native.”

**********

It was Saturday morning, the day of the Big Race, and we were having breakfast in a plastic hamburger palace called the Fish-MeatVillage. Our rooms were just across the road in the Brown Suburban Hotel. They had a dining room, but the food was so bad that we couldn’t handle it anymore. The waitresses seemed to be suffering from shin splints; they moved around very slowly, moaning and cursing the “darkies” in the kitchen.

Steadman liked the Fish-Meat place because it had fish and chips. I preferred the “French toast,” which was really pancake batter, fried to the proper thickness and then chopped out with a sort of cookie cutter to resemble pieces of toast.

Beyond drink and lack of sleep, our only real problem at that point was the question of access to the clubhouse. Finally, we decided to go ahead and steal two passes, if necessary, rather than miss that part of the action. This was the last coherent decision we were able to make for the next forty-eight hours. From that point on–almost from the very moment we started out to the track–we lost all control of events and spent the rest of the weekend churning around in a sea of drunken horrors. My notes and recollections from Derby Day are somewhat scrambled.

But now, looking at the big red notebook I carried all through that scene, I see more or less what happened. The book itself is somewhat mangled and bent; some of the pages are torn, others are shriveled and stained by what appears to be whiskey, but taken as a whole, with sporadic memory flashes, the notes seem to tell the story. To wit:**********

Rain all nite until dawn. No sleep. Christ, here we go, a nightmare of mud and madness…But no. By noon the sun burns through–perfect day, not even humid.

Steadman is now worried about fire. Somebody told him about the clubhouse catching on fire two years ago. Could it happen again? Horrible. Trapped in the press box. Holocaust. A hundred thousand people fighting to get out. Drunks screaming in the flames and the mud, crazed horses running wild. Blind in the smoke. Grandstand collapsing into the flames with us on the roof. Poor Ralph is about to crack. Drinking heavily, into the Haig & Haig.

Out to the track in a cab, avoid that terrible parking in people’s front yards, $25 each, toothless old men on the street with big signs: PARK HERE, flagging cars in the yard. “That’s fine, boy, never mind the tulips.” Wild hair on his head, straight up like a clump of reeds.

Sidewalks full of people all moving in the same direction, towards Churchill Downs. Kids hauling coolers and blankets, teenyboppers in tight pink shorts, many blacks…black dudes in white felt hats with leopard-skin bands, cops waving traffic along.

The mob was thick for many blocks around the track; very slow going in the crowd, very hot. On the way to the press box elevator, just inside the clubhouse, we came on a row of soldiers all carrying long white riot sticks. About two platoons, with helmets. A man walking next to us said they were waiting for the governor and his party. Steadman eyed them nervously. “Why do they have those clubs?”

“Black Panthers,” I said. Then I remembered good old “Jimbo” at the airport and I wondered what he was thinking right now. Probably very nervous; the place was teeming with cops and soldiers. We pressed on through the crowd, through many gates, past the paddock where the jockeys bring the horses out and parade around for a while before each race so the bettors can get a good look. Five million dollars will be bet today. Many winners, more losers. What the hell. The press gate was jammed up with people trying to get in, shouting at the guards, waving strange press badges: Chicago Sporting Times, Pittsburgh Police Athletic League…they were all turned away. “Move on, fella, make way for the working press.” We shoved through the crowd and into the elevator, then quickly up to the free bar. Why not? Get it on. Very hot today, not feeling well, must be this rotten climate. The press box was cool and airy, plenty of room to walk around and balcony seats for watching the race or looking down at the crowd. We got a betting sheet and went outside.

**********

Pink faces with a stylish Southern sag, old Ivy styles, seersucker coats and buttondown collars. “Mayblossom Senility” (Steadman’s phrase)…burnt out early or maybe just not much to burn in the first place. Not much energy in the faces, not much curiosity. Suffering in silence, nowhere to go after thirty in this life, just hang on and humor the children. Let the young enjoy themselves while they can. Why not?

The grim reaper comes early in this league…banshees on the lawn at night, screaming out there beside that little iron nigger in jockey clothes. Maybe he’s the one who’s screaming. Bad DT’s and too many snarls at the bridge club. Going down with the stock market. Oh Jesus, the kid has wrecked the new car, wrapped it around the big stone pillar at the bottom of the driveway. Broken leg? Twisted eye? Send him off to Yale, they can cure anything up there.

Yale? Did you see today’s paper? New Haven is under siege. Yale is swarming with Black Panthers…I tell you, Colonel, the world has gone mad, stone mad. Why, they tell me a goddam woman jockey might ride in the Derby today.

I left Steadman sketching in the Paddock bar and went off to place our bets on the fourth race. When I came back he was staring intently at a group of young men around a table not far away. “Jesus, look at the corruption in that face!” he whispered. “Look at the madness, the fear, the greed!” I looked, then quickly turned my back on the table he was sketching. The face he’d picked out to draw was the face of an old friend of mine, a prep school football star in the good old days with a sleek red Chevy convertible and a very quick hand, it was said, with the snaps of a 32 B brassiere. They called him “CatMan.”

But now, a dozen years later, I wouldn’t have recognized him anywhere but here, where I

should have expected to find him, in the Paddock bar on Derby Day…fat slanted eyes and a pimp’s smile, blue silk suit and his friends looking like crooked bank tellers on a binge…

Steadman wanted to see some Kentucky Colonels, but he wasn’t sure what they looked like. I told him to go back to the clubhouse men’s rooms and look for men in white linen suits vomitting in the urinals. “They’ll usually have large brown whiskey stains on the front of their suits,” I said. “But watch the shoes, that’s the tip-off. Most of them manage to avoid vomitting on their own clothes, but they never miss their shoes.”

In a box not far from ours was Colonel Anna Friedman Goldman, Chairman and Keeper of the Great Seal of the Honorable Order of Kentucky Colonels. Not all the 76 million or so Kentucky Colonels could make it to the Derby this year, but many had kept the faith, and several days prior to the Derby they gathered for their annual dinner at the Seelbach Hotel.

The Derby, the actual race, was scheduled for late afternoon, and as the magic hour approached I suggested to Steadman that we should probably spend some time in the infield, that boiling sea of people across the track from the clubhouse. He seemed a little nervous about it, but since none of the awful things I’d warned him about had happened so far–no race riots, firestorms or savage drunken attacks–he shrugged and said, “Right, let’s do it.”

To get there we had to pass through many gates, each one a step down in status, then through a tunnel under the track. Emerging from the tunnel was such a culture shock that it took us a while to adjust. “God almighty!” Steadman muttered. “This is a…Jesus!” He plunged ahead with his tiny camera, stepping over bodies, and I followed, trying to take notes.

**********

Total chaos, no way to see the race, not even the track…nobody cares. Big lines at the outdoor betting windows, then stand back to watch winning numbers flash on the big board, like a giant bingo game.

Old blacks arguing about bets; “Hold on there, I’ll handle this” (waving pint of whiskey, fistful of dollar bills); girl riding piggyback, T-shirt says, “Stolen from Fort Lauderdale Jail.” Thousands of teen-agers, group singing “Let the Sun Shine In,” ten soldires guarding the American flag and a huge fat drunk wearing a blue football jersey (No. 80) reeling around with quart of beer in hand.

No booze sold out here, too dangerous…no bathrooms either. MuscleBeach…Woodstock…many cops with riot sticks, but no sign of a riot. Far across the track the clubhouse looks like a postcard from the Kentucky Derby.

**********

We went back to the clubhouse to watch the big race. When the crowd stood to face the flag and sing “My Old Kentucky Home,” Steadman faced the crowd and sketched frantically. Somewhere up in the boxes a voice screeched, “Turn around, you hairy freak!” The race itself was only two minutes long, and even from our super-status seats and using 12-power glasses, there was no way to see what really happened to our horses. Holy Land, Ralph’s choice, stumbled and lost his jockey in the final turn. Mine, Silent Screen, had the lead coming into the stretch but faded to fifth at the finish. The winner was a 16-1 shot named Dust Commander.

Moments after the race was over, the crowd surged wildly for the exits, rushing for cabs and busses. The next day’s Courier told of violence in the parking lot; people were punched and trampled, pockets were picked, children lost, bottles hurled. But we missed all this, having retired to the press box for a bit of post-race drinking. By this time we were both half-crazy from too much whiskey, sun fatigue, culture shock, lack of sleep and general dissolution. We hung around the press box long enough to watch a mass interview with the winning owner, a dapper little man named Lehmann who said he had just flown into Louisville that morning from Nepal, where he’d “bagged a record tiger.” The sportswriters murmured their admiration and a waiter filled Lehmann’s glass with Chivas Regal. He had just won $127,000 with a horse that cost him $6,500 two years ago. His occupation, he said, was “retired contractor.” And then he added, with a big grin, “I just retired.”

The rest of the day blurs into madness. The rest of that night too. And all the next day and night. Such horrible things occurred that I can’t bring myself even to think about them now, much less put them down in print. I was lucky to get out at all. One of my clearest memories of that vicious time is Ralph being attacked by one of my old friends in the billiard room of the Pendennis Club in downtown Louisville on Saturday night. The man had ripped his own shirt open to the waist before deciding that Ralph was after his wife. No blows were struck, but the emotional effects were massive. Then, as a sort of final horror, Steadman put his fiendish pen to work and tried to patch things up by doing a little sketch of the girl he’d been accused of hustling. That finished us in the Pedennis.

**********

Sometime around ten-thirty Monday morning I was awakened by a scratching sound at my door. I leaned out of bed and pulled the curtain back just far enough to see Steadman outside. “What the fuck do you want?” I shouted.

“What about having breakfast?” he said.

I lunged out of bed and tried to open the door, but it caught on the night-chain and banged shut again. I couldn’t cope with the chain! The thing wouldn’t come out of the track–so I ripped it out of the wall with a vicious jerk on the door. Ralph didn’t blink. “Bad luck,” he muttered.I could barely see him. My eyes were swollen almost shut and the sudden burst of sunlight through the door left me stunned and helpless like a sick mole. Steadman was mumbling about sickness and terrible heat; I fell back on the bed and tried to focus on him as he moved around the room in a very distracted way for a few moments, then suddenly darted over to the beer bucket and seized a Colt .45. “Christ,” I said. “You’re getting out of control.”

He nodded and ripped the cap off, taking a long drink. “You know, this is really awful,” he said finally. “I must get out of this place…” he shook his head nervously. “The plane leaves at three-thirty, but I don’t know if I’ll make it.”

I barely heard him. My eyes had finally opened enough for me to foucs on the mirror across the room and I was stunned at the shock of recognition. For a confused instant I thought that Ralph had brought somebody with him–a model for that one special face we’d been looking for. There he was, by God–a puffy, drink-ravaged, disease-ridden caricature…like an awful cartoon version of an old snapshot in some once-proud mother’s family photo album. It was the face we’d been looking for–and it was, of course, my own. Horrible, horrible…

“Maybe I should sleep a while longer,” I said. “Why don’t you go on over to the Fish-Meat place and eat some of those rotten fish and chips? Then come back and get me around noon. I feel too near death to hit the streets at this hour.”

He shook his head. “No…no…I think I’ll go back upstairs and work on those drawings for a while.” He leaned down to fetch two more cans out of the beer bucket. “I tried to work earlier,” he said, “but my hands kept trembling…It’s teddible, teddible.”

“You’ve got to stop this drinking,” I said.

He nodded. “I know. This is no good, no good at all. But for some reason it makes me feel better…”

“Not for long,” I said. “You’ll probably collapse into some kind of hysterical DT’s tonight–probably just about the time you get off the plane at Kennedy. They’ll zip you up in a straightjacket and drag you down to the Tombs, then beat you on the kidneys with big sticks until you straighten out.”

He shrugged and wandered out, pulling the door shut behind him. I went back to bed for another hour or so, and later–after the daily grapefruit juice run to the Nite Owl Food Mart–we had our last meal at Fish-MeatVillage: a fine lunch of dough and butcher’s offal, fried in heavy grease.

By this time Ralph wouldn’t order coffee; he kept asking for more water. “It’s the only thing they have that’s fit for human consumption,” he explained. Then, with an hour or so to kill before he had to catch the plane, we spread his drawings out on the table and pondered them for a while, wondering if he’d caught the proper spirit of the thing…but we couldn’t make up our minds. His hands were shaking so badly that he had trouble holding the paper, and my vision was so blurred that I could barely see what he’d drawn. “Shit,” I said. “We both look worse than anything you’ve drawn here.”

He smiled. “You know–I’ve been thinking about that,” he said. “We came down here to see this teddible scene: people all pissed out of their minds and vomitting on themselves and all that…and now, you know what? It’s us…”

**********

Huge Pontiac Ballbuster blowing through traffic on the expressway.

A radio news bulletin says the National Guard is massacring students at KentState and Nixon is still bombing Cambodia. The journalist is driving, ignoring his passenger who is now nearly naked after taking off most of his clothing, which he holds out the window, trying to wind-wash the Mace out of it. His eyes are bright red and his face and chest are soaked with beer he’s been using to rinse the awful chemical off his flesh. The front of his woolen trousers is soaked with vomit; his body is racked with fits of coughing and wild chocking sobs. The journalist rams the big car through traffic and into a spot in front of the terminal, then he reaches over to open the door on the passenger’s side and shoves the Englishman out, snarling: “Bug off, you worthless faggot! You twisted pigfucker! [Crazed laughter.] If I weren’t sick I’d kick your ass all the way to Bowling Green–you scumsucking foreign geek. Mace is too good for you…We can do without your kind in Kentucky.”