V. K. Reiter’s

My Girodias

The first time I saw Maurice Girodias he was leaning against the door of a porte-cochère, kissing a one-eyed woman. I do not know if this was the end of their affair, or a remnant of it, but in the first years I knew him she would often be there in some capacity, saving him from ruin, listening to his ranting or trying to help him focus on a business decision.

I’d been sent to Girodias by Walter Wanger, the Hollywood producer who had taken an option on my first novel but would never turn it into a movie, side-tracked by Liz Taylor/Richard Burton in “Cleopatra.” Wanger was an old Hollywood hand famous for his gentlemanly front, for a fair number of smartish films and for having done time after shooting his wife, the actress Joan Bennett’s, lover in the groin. When he learned I was leaving for Paris, he invited me to a private screening of a new Ingmar Bergman movie, introduced me to a starlet he was wooing and who he had obviously promised the leading part in my never-to-be-produced movie, and handed me a dozen letters of introduction to people in Paris. I was twenty-one and unschooled in the etiquette surrounding such letters so I took them home and read them. The letter to Girodias, famous as the publisher of The Olympia Press, home of avant-garde literature and at times witty pornography, was particularly succulent and included mention of my having written a novel full of sex. That was the universal response then in Hollywood: everyone there thought the novel was full of sex when it was actually full of anger but for a while it made me interesting to men in the industry who had not noticed me before.

Once in Paris, I sent the letter to Girodias along with a copy of my novel. He invited me to visit his offices and that is where I first saw M., the one-eyed woman who had married into a great banking family but did not act the part. I would soon meet several of the other smart women Girodias maintained in orbit around him, some French, some Americans from New York, all of whom spoke in bold voices tinged with irony.

That first day, I was invited to return later to meet Lawrence Durrell, a short, aggressive man who throughout the evening stood in a corner, ready to take on all comers. Durrell had already published his “Alexandria Quartet” to great acclaim but had written another book which no publisher seemed willing to take on, except Girodias. As usual, the Olympia Press edition would become famous and later be taken over by publishing houses in London and New York, causing Girodias the same fury and anguish he often inflicted on many of his writers.

Girodias had come into possession of a wreck of a mid-18th century building on rue St. Severin, off boulevard St. Michel. The stairway had a wrought-iron hand-rail; the floors creaked and the windows in the back were difficult to open. In the winter there was heat, obviously added sometime in the second quarter of the 20th century, and the offices were further insulated by books and papers piled up against the inner walls. One flight above the office was an apartment, half-empty of furniture, one of Girodias’ domiciles in Paris. At the time I met him, he was for the most part living on the fashionable Place St. Germain des Près, in those days pressing out the last dregs of the existentialist brew that had made Paris so magnetic directly after World War II. At the beginning of our friendship, Girodias spoke to me of his father, Jack Kahane, who had begun the Olympia Press in the 1930s, publishing Henry Miller and the biography of Frank Harris. During the Second World War, having inherited the house and its back-list, Girodias camouflaged his antecedents by taking his mother’s maiden name and hid out in a maid’s room on the Place Vendome, directly across from the Ritz. At first, he rarely spoke to me of his romantic entanglements, except for the history of his one marriage and the daughters born of it but later he recounted in scatological detail his enchantment with a very tall, black American woman whose Southern country directness and blues-singer ways he found irresistible but who would eventually turn violent on him. Our last detailed conversation about that affair took place on the day after she had beaten him to the floor in the lobby of her small hotel and he called the police, who carted both of them off to the city hospital. All his writers were enraged with Girodias but it took a Carolina woman to express that indignation in concrete terms.

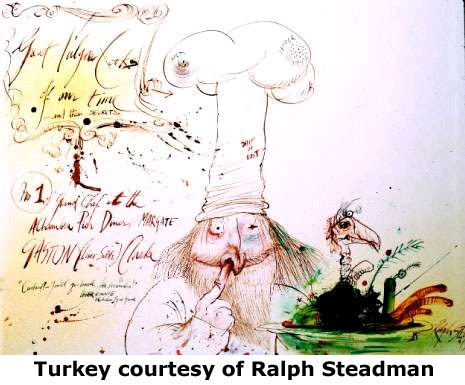

Over the next ten years, I too moved in and out of Girodias’ orbit, dropping by the offices on rue St. Severin to spend an hour with him, or working for him a while on some project or other. He had transformed the building, establishing a nightclub and restaurant complex named La Grande Severine on the ground and second floors and in the cellar. Each venue was physically beautiful, the kitchen was run by a 90-year old Georgian chef, and the ambience was brilliant and romantic. The ground floor held a Russian restaurant and cabaret; the large cellar, a small theater and a space that began as a poetic sort of winter-garden but evolved into a Brazilian nightclub; and the second floor was the Blues Bar where the Carolina blues singer, among others, performed. Unfortunately, when Girodias, who drank to excess, opened La Grande Severine he comped all his acquaintances who took it for granted that state of affairs would continue: this prolonged hospitality cost him money and in due course, a phrase that was a tic in his own writing, helped lead to the failure of the complex. But at the beginning, the place was magical. Evenings in the Blues Bar, I watched the forever cool Girodias rabbit after the blues singer as she finished her set and strode off the stage. On one of my birthdays, Girodias offered me an impromptu party at the Russian restaurant, ordering up chocolate soufflés and champagne, and telling the Russian orchestra to play any song I requested. Because he had no actual gift to hand me, Girodias picked up a wine glass and ate it, gazing into my eyes as he bit off the edges, chewing the pieces fine and then swallowing the dust. This must have been a well-practiced trick for I saw no blood.

Several years later, after my French divorce from my American husband, I went to work full-time for Girodias, acting, among other things, as his American “expert” whenever he wrote his long-winded, many paged, single-space letters of threats and complaints to those who had done him wrong, translating them from Girodias’ early 20th century, awkwardly British English into American. When New English Library purchased British publishing rights to some of his books, I travelled with him to London for a Foyle’s luncheon, and to Oxford where he was to be the guest debater at the Oxford Union, breeding ground of British prime ministers and others of that ilk. I’d managed to convince him to focus on his presentation at the luncheon but having drunk an inordinate amount of wine, he’d meandered and muttered. One of the behatted ladies attending the luncheon turned to her table companion and said, “I thought this was to be about the gods of Olympus.”

I urged him to prepare seriously for the Oxford Union where he was to argue against the proposition: “Censorship Has a Legitimate Place in the Government’s Influence on Social Values.” Arguing for the proposition would be the British government’s official censor who had just closed down three London plays. I had attempted to describe the forms and rituals practiced at the Debates, but of course Girodias did not prepare, other than to get drunk beforehand, but instead presented a confused tale of his life in publishing in guise of an argument. Of course, at the end of the evening, he and the two students who had also spoken, brilliantly, against censorship won the debate on an ideological basis. I watched as future prime ministers and members of Parliament passed back and forth through the Union’s doors in order to ring the traditional voting bell that hung there and was sounded to indicate a vote was being cast.

Having procured a work permit in my name, Girodias was paying me the equivalent of forty dollars a week. I was living at the Hotel des Marroniers in St. Germain des Près, renting a small room with its own bath, a rarity in those days. I’d bought a tiny can of propane, added a wire frame atop it to hold a pot, placed this camping stove in the bidet and cooked my meals there. There were evenings when I had two or three dinner guests: each one brought a plate, silverware and a glass. I cooked in the bidet, using the hot water in the sink and in the bottom of the sitz-bath to keep the pots warm, and we sat on the bed. All this local color could not last and eventually I resigned and looked for work elsewhere.

A year or so later Girodias was being forced out of rue St. Severin and into a smaller ground-floor office in an unheated 17th century stone building that formerly housed a religious publishing house. He asked that I return to help with the move and to organize the new place but he already had a steadfast American girl working for him, much better equipped for the task than I and not yet irritated enough with him for irony to color her conversation.

Two years later, Girodias telephoned to ask if I knew of someone who might act as an editor at the Olympia Press office he was opening in New York. I had been thinking of returning to the States. “What about me?” I asked, “Fly me back to New York, find me a place to live, and pay me a living wage.”

He immediately agreed and within six weeks I had turned over my apartment and furniture to a handsome young man who had once been the heiress Barbara Hutton’s personal photographer, packed two trunks to be sent by sea, two pieces of luggage to accompany me on the plane, and purchased a carrier for my Paris-born Maine Coon cat. The flight was delayed for eleven hours and my first gesture upon my return to America was to hold my cat over a patch of grass outside Customs so that she could pee.

Girodias had taken a room for me at the Chelsea Hotel. My second evening there I met a woman in the lobby who was wearing startling white lace jeans and a velvet top, and asked her where she had found the jeans. “San Francisco,” she said in a raspy voice. I introduced myself and she said her name was Janice Joplin but this meant nothing to me as I had been away a long time and had not been following American popular culture.

At first, Olympia Press New York was Girodias’ suite in the Chelsea. There I met the Italian poet and dramatist Aldo Rostagno, the art director for Bantam Books and, in his spare time, doing the same for Olympia. He became a good friend and, when he and his family returned to Italy, I would visit them in the farmhouse outside Florence that they leased from a local contessa. But on that first day, Aldo showed Girodias some bills he’d received and asked what he should do with them.

“Give them to V; she’ll take care of them,” and I realized I had been imported to be his assistant and office manager, not his editor. This was the first time Girodias had lied to me so egregiously that my anger would not abate. In the past he had underpaid me, or overworked me, or put me in the position of having to charm writers out of their exasperation with him but all that had been understood before I signed up for the job and was no surprise. Now I would spend some months helping furnish his apartment/office on Gramercy Park, see to the administrative work, help him open a business bank account on which my signature was added for efficiency’s sake, pay his employees and generally run the place. Given my salary, the Chelsea Hotel was far too expensive so I sublet a small apartment in Greenwich Village from Iris Owens, one of Girodias’ most talented and interesting writers, who was leaving the city in order to finish a novel.

Eventually, Girodias asked me to read an eight hundred page manuscript by Ronald Tavel, one of Andy Warhol’s partners in the Theater of the Ridiculous. Girodias wanted to publish it but he needed the manuscript edited down to four hundred pages, a painful business as Tavel did not want his manuscript mutilated. At a luncheon Girodias arranged for us, Tavel and I reached a nervous understanding and I began work, cutting out wonderful descriptive passages and strange, contorted plot to produce a distorted but publishable piece.

On a plane from somewhere to somewhere, Girodias had met an Arizona printer who he convinced to bankroll him in exchange for the right to print his books. Along with his imprint, Girodias had transferred his Paris behavior to New York and so was ignoring the U.S. Social Security and Internal Revenue systems and all such governmental adjuncts as he could. In France this, and his more outrageous pornography, had led him to court several times over the years but he had managed to extend the tolerance he enjoyed there for decades and so did not take these matters seriously. Besides, he had a couple of well-placed New York lawyers representing him and seemed to believe he was covered. Since I was a signatory on the business account, I withheld and reported such taxes as demanded by American law. Girodias was incensed.

One day, again short of money but holding a registered check from the Arizona printer, Girodias asked me to find a way to sidestep the then ten-day waiting period before he could get his hands on the cash. I telephoned an acquaintance of mine, a French banker living in the United States who believed himself well acclimated although, he told me, in his twenty years in New York he had never tasted pastrami. I explained the problem to him; he said I was to have Girodias endorse the check and then bring it to him at the New School where he was taking a ballet class. That evening my banker friend transferred the amount into Girodias’ checking account. As this was a favor to me, he took no vig. I suggested Girodias send a gift in thanks, and told him the banker drank Sancerre. A dozen bottles were ordered and delivered, with a note. The next day I listened in on the telephone as those two profligate Frenchmen exchanged the most extravagant courtesies heard in New York since General George Washington greeted foreign dignitaries come to watch him lose another battle in the Revolutionary war.

Very soon after this, pages of blank checks began disappearing from the back of the company’s check book and there were no notations indicating how they had been used. Girodias would not answer my questions about the missing checks so I immediately removed my name from the company bank account, returned to the office and resigned.

Before leaving Paris, I had met movie producer Sidney Glazer who invited me to visit his production office on 56th Street. My third night in New York he invited me to a showing of his new film, directed by Mel Brooks, of whom I had never heard. The film was an un-color-corrected, mostly un-scored copy of “The Producers,” and I laughed myself sick. Soon, I was doing some writing for the production company and when the time came, I could almost afford to quit Girodias.

We did keep in touch for a while. I told him of my remarriage and, in return, heard of the new employees and then the newer ones, the drinking, the affairs, the lessening number of books published. Three years after I left Olympia, a desperate Girodias, whose fortunes had plummeted, published a plagiarized, pornographic version of a best-selling novel written by a friend of mine. When sued, he tried to blackmail the writer with whom I once had a very long, very discreet affair. The blackmail attempt failed. I never spoke with Girodias again although, from time to time, I heard of his doings, his own marriage to an American woman, his forced return to France, his loss of the Olympia Press to one of his old, put-upon writers who out-bid him for it at the bankruptcy auction, his poverty and the grace with which he tried to hide it, the publication of the first two volumes of his autobiography and, eventually, his renewed reputation. At the very end it seems that he finally embraced his own father’s background: Girodias’ last public appearance was an interview on a Jewish radio station in Paris. At the end, the interviewer signed off and right there, l’Envoi, Girodias did too.

| V.K. Reiter has published nine novels, translated over a dozen French novels for publication in the U.S., including Maryse Condé’s “Tree of Life” and five of Daniel Odier’s “Delacorta” series. She has ghost-written three films and served as a free-lance editor on several best-selling books. While living in France, she wrote and translated narration for documentary films, was a reader and editor for Les Editions Robert Laffont and spent five interesting years as editor and consultant to Maurice Girodias, publisher of The Olympia Press. At present she has a novel in progress, “The Memoirs of Sister Warren Lecroix Falconer,” and is also compiling a series of memory pieces, the first of which, Their Graces, appeared in the Summer 2011 issue of Eclectica Magazine and the second, An Afternoon With Salvador Dali (http://www.eclectica.org/v16n1/reiter.html ) in its Winter 2012 issue. Her creative non-fiction essay, “Transport,” published in the Autumn issue of Rosebud Magazine, won the 2013 X. J. Kennedy Writing Award. She lives in New York. |

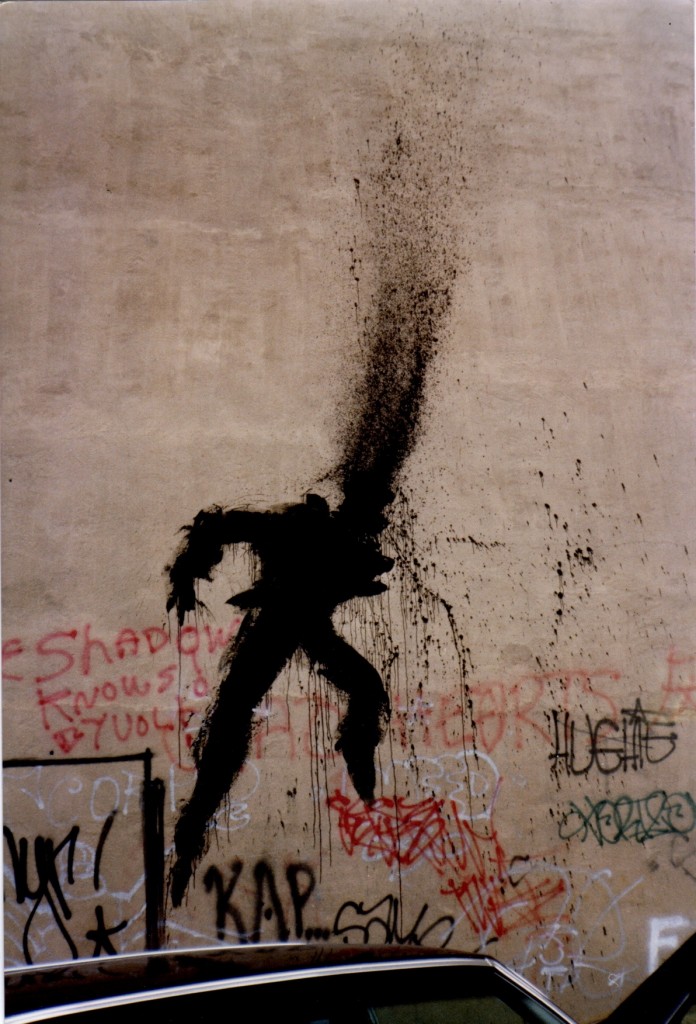

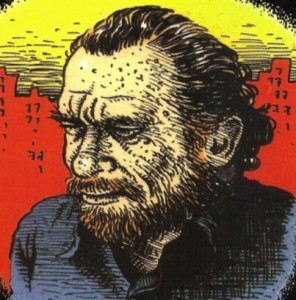

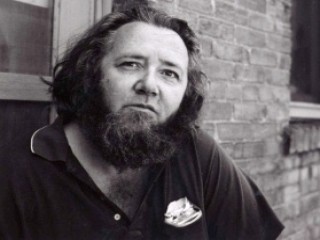

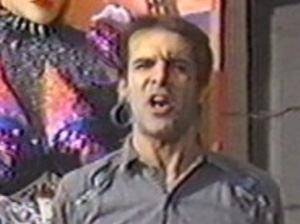

Maurice Girodias, Paris, 1990

Maurice Girodias, Paris, 1990