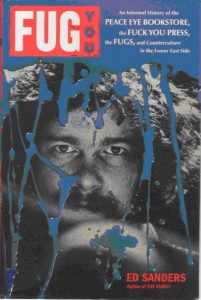

Victor Harwood’s

THE WRITERS’ CONFERENCE

excerpted from his novel

TO DIE IN MADRID

THE WRITERS’ CONFERENCE

excerpted from his novel

TO DIE IN MADRID

How would I measure up to the toast of Paris, André Malraux, the hero of the Rive Gauche? We all start out as equals but Malraux’s name was carved into the wooden tables at the Deux Magots. While I was in Berlin, Malraux was with Mao Tse-Tung in China on the Long March and when he returned he did more than mark time and wander the cafés in the Quarter, he composed La Condition Humaine, he wrote the great novel of his day. He was a man to fear.

“This is Monsieur Devlin?” I listened to his voice on the hotel Écoles lobby telephone. “This is Malraux. I have spoken with Broz.” I had expected the call. Broz had contacted Ginger and he let me know that the pieces of a grand plan were in place. The French were about to complete the sale of a squadron of airplanes to Spain and André Malraux, French Prime Minister Blum’s advisor on foreign affairs, had been chosen to coordinate the affair. “Broz thinks a meeting would be useful. He speaks highly of you.” Malraux said. The sale of the air squadron to Spain was front page news in Paris. I was excited at the thought of playing a role. I was flattered. It was the story of the day.

“Monsieur Malraux.” A reporter had asked him on a radio show the evening before. “If France didn’t object to the loss of the Rhineland to the Germans, why must we get ourselves involved in a civil war in Spain?” It was a fair question. Four months earlier Hitler’s army had marched in and occupied the demilitarized zone along France’s eastern border, crossing the Rhine, taking back land it had signed away to the French in the Treaty of Versailles and in the months that had passed, France along with its allies England and the United States had done nothing to push the Germans back.

“If I may beg your indulgence,” Malraux, who possessed a cultured arrogance, answered, “on June 5 France elected a new government with a new politique and it is the policy of our Prime Minister that Spain be supported. That is why I believe we were elected. We call it the prívilége of power.”

“Do we now re-evaluate our policy toward Germany and the Rhineland?” The reporter followed.

“I do not suggest that Monsieur,” Malraux said. “We are not a government that can turn back the clock. But that is a question you may address to Minister Blum if you wish.”

“Monsieur Malraux,” the journalist continued, “if we ally with Spain, what do you expect of Mussolini?” In his answer Malraux neatly side-stepped his government’s greatest dilemma, the viability of its very existence. France had fascist Germany on one side, fascist Italy on another and a threat of an internal fascist coup. Even the loyalties of England were in question. Anthony Eden’s government had more in common with the German Chancellor than with the Socialist Prime Minister of France.

Malraux finessed. “You must be naive, Monsieur Journaliste,” he said. “Mussolini has already assisted the Franco coup attempt. We have no choice. It is common sense. If Spain falls, France will have fascist states on three sides.”

“But Germany and England have declared that they will remain neutral.” The reporter said. “Are you willing to risk forcing their hand?”

“Monsieur, France did not invade Spain. Italy and Germany will serve their interest as France will hers.”

The decision to support Spain had been made and the delivery of an air squadron with full logistical support would be enacted. For our meeting, Malraux had suggested the Dingo, since we both lived in the district and I rang up Jimmy Charters and reserved one of the private banquettes under the mural along the back wall.

That Saturday night Malraux and I sat side-by-side, facing the room, watching the crowd flow in and out in waves as it passed through the Dingo, quick to find out what was doing in the Quarter, savor a Jimmy Charters Gin Fizz and head off for dinner at the Brassarie Lipp or the Dôme. On Saturday nights the Boulevard Montparnasse was still flush with the bohemian madness of the past era. It was still an intoxication.

“Have you ever wondered why the cafés become what they are Devlin?” Malraux was totally at ease, at home along the banquette. “I can never understand it and I’ve sat at these tables my whole life. You go where you want to be seen I suppose, unless you’re Sartre and then you choose to sit by yourself, but that is Sartre. The rest go to be seen. Picasso still holds court at the Deux Magots, and you might like to know that while he was in Parisian exile, the quiet La Mahieu on the Boulevard Saint Michel was Monsieur Lenin’s Académie Communiste. The café marks the man. Where he makes his nest. They tell me that you are partial to the Dôme. For Kiki. It is a good choice.” There were no secrets in the quarter.

From the moment we sat down, Malraux talked and sipped café creme and his eyes wandered about the room keeping watch on the strangers. It was ritual. He didn’t pause to breathe. He sipped espresso and observed.

“One year ago Gide and I sat at that table over there,” Malraux pointed with his finger toward the corner booth near the swinging kitchen doors. “No one bothered with us, we sat there for days planning the Congress in Defense du Culture, the Writer’s Congress. Le Dingo American was the perfect place, a café where we could be completely invisible. Phantoms that didn’t exist. Even now I can walk over to the bar and no one would know me, they wouldn’t know Gide. We have these separate worlds, you and I, the French and the Americans. Everything is a separate world. Would you agree? I accept it. I like it that way. It makes for a mystery which is good I think. Without mystery what do you have? Look toward that magnificent woman,” he pointed toward the bar, “the one with the exquisite shape. For this moment she is my mystery. Look at her eyes! It is a pity that I will never know her. Forever my mystery. That’s the way it was meant to be, don’t you agree Devlin? She will linger in my imagination. It is desire that makes for a better man.”

Malraux’s eye and cheek began to flutter. I had known that he suffered from a facial tick, but when it showed itself it was jolting and I couldn’t help but stare.

“It is nothing Devlin. Don’t mind it, please. It will pass,” he continued the conversation where it had left off.

“We were at that table when Gide gave me the news that Gorki wouldn’t be able to come to the Congress. What a disaster. Gorki was our star. ‘That is impossible, André!’ I said. ‘It is the Congress du Paris, our defense of Europe. Who will speak for the Soviets? For the new vision? There is no one but Gorki,’ I said but André was calm.

“‘I have already picked out the perfect replacement. It will change nothing. I am confident. I have chosen Pasternak the brilliant poet. We will get Pasternak,’ he said. ‘The Congress will be a triumph.’

“Gide decided on Pasternak at Le Dingo. It was done. He was content. I had met Gorki the year before in Moscow. He was a great man. It made me sure. But if Gide was confident with Pasternak then so was I.

“A few weeks later the Congress du Paris was upon us and along with thousands of writers from around the world, Pasternak arrived. We dined at La Coupole and celebrated. The impossible had been accomplished. Our year of planning was complete. The Congress would convene and Pasternak would address the opening session.

“Three thousand of the world’s greatest writers raised to their feet and stood in applause that night. ‘Bravo Pasternak.’ They cried. ‘Bravo! The poet from the great Soviet.’ The Congress was a success. He was gracious, he thanked Gide for bringing him, he had kind words for Gorki and carried a message from him which he read. Then Pasternak made the speech of his lifetime and it was our debacle. He was our saboteur.

” ‘I was not certain at first if I should make the journey.’ Pasternak had an unforgettable voice. So calm. ‘But I am told that I am Comrade Stalin’s favorite poet and he himself asked that I represent the Soviet writer here in Paris, a noble distinction and for that I am honored.

” ‘But I am a simple fool. By temperament, I would choose to remain in Russia, to sit at my desk. ‘But you have been chosen,’ my comrades urged. ‘You can not refuse. You can not refuse,’ they said and I understood. I am the court poet. I am a Soviet writer. I must pay for my privilege. There is the price in every profession. Is it the same for the rest of you? To be chosen to stand among the greatest writers in the world?

” ‘But I am a writer,’ Pasternak said, ‘I can hardly speak for a country. I speak in a whisper with a little voice. It can barely be heard.’ Pasternak was brilliant that night. Measured. Unique. ‘So I must ask you if it is not too impertinent. Why have you all come here this night. I . . . I know that I have not been coerced. That is what makes it all the more odd. What has compelled us? By our nature writers do not come together in groups.’ He said. ‘A Congress of writers? That is somewhat absurd. A writer does not seek power. I can barely raise my pen above the desk. I am the lowly court poet. Why I am here?’ I was sitting in a mezzanine box above the stage and I looked at Gide.

“What did he say? I whispered to Gide. Where is he taking us?”

” ‘A Writer’s Congress is the death of art to be sure. A writer does not serve a political master. That is wrong. That is impossible. That is against all art and I am nothing if I’m not an artist,’ he said. The very purpose of the Congress had been attacked. ‘A writer reads poems,’ he said and Pasternak began reading: ‘It is wilting in the summer heat. Dry as bone. Its leaves fade, dry out and decay. In the winter the bark cracks from cold, and it is dead and hollow. The tree.’

“We had been deceived! ‘Petit bourgeois! Traitor!’ Shouts came from the floor. ‘Petit bourgeois! Traitor!’ He had attacked the Soviets and the Artiste du Guerrier forced him from the podium.” Malraux ran his hand back threw his hair. “The Congress was in shambles. It was a disaster. Pasternak was forced from the stage. A fiasco. Our night was ruined and we returned to the Dingo and drank.

” ‘To le débâcle.’ Gide raised his glass. ‘Three thousand writers in Paris and none can be trusted,’ ” he said.

“Never trust a writer.” Malraux laughed as he remembered the thought. “We were fools to place our trust in them!”

Malraux was modest in referring to the Congress du 1935. The event was legend in the Quarter. It was the symbol of the new art versus the old, the Surrealists standing down the Communist Politique. Pasternak’s visit to Paris was epochal.

Even I had heard that on that first night of the Congress, while Gide and Malraux drank at the Dingo, a few blocks further down the Boulevard Montparnasse at the Closerie des Lilas the great Surrealists of Paris, André Breton, René Magritte, Dali, Man Ray and Max Ernst celebrated their good fortune, calling it the night of divine intervention. For months Malraux and Gide’s Committee had maneuvered the Surrealists, keeping them out of the Congress. It had been a constant struggle and until that night, they had succeeded.

As the story goes, on an afternoon a few days before the event, Breton and his Surrealists actually ambushed Malraux in the middle of the Boulevard Montparnasse, herding him into the center of a mob of students.

“You can not control history, Malraux. It will eat you alive! We will hunt you down, come to haunt your dreams, Malraux,” Breton had shouted.

“You are mad, Breton.” Malraux made his way through, escaping to the other side.

“We are artists, Malraux. You cannot kidnap history! You cannot make it Russian!” Breton chased after him. It was war in the Quarter between the Surrealists and the Social Realists, the artists in defense of Soviet Russia. And until Pasternak arrived in Paris, history had belonged to them.

But at the Closerie after Pasternak’s address, the Surrealists drew up another of their infamous broadsheets. It was called The Pasternak Manifesto, accusing Malraux of conspiring with the Kremlin in the organization of the Congress. It demanded that the poet be returned to the podium and by morning their Manifesto was re-printed in every Parisian daily paper and all the cafés had it posted on their walls. The treatment of Pasternak had disgraced all Parisians. The Surrealists had triumphed.

That night Pasternak was again on the podium and the streets surrounding the auditorium were filled with a Surrealist army chanting, “Da-Da. Da-Da. Da-Da. Da-Da.” But on the inside Gide and Malraux’s delegates still outnumbered Breton, Magritte and their band. The atmosphere was explosive.

“I have a letter from Victor Serge!” Pasternak began. The name of Victor Serge was all that the Gide delegates had needed to hear. It was a spark. “This great writer has been kidnapped by the Soviet state! He is a prisoner!” Pasternak cried out and his voice was buried beneath a sea of cat-callers.

“Pasternak Provocateur, Pasternak Provocateur,” they cried. Serge’s name was code for political heresy. He had been tried and branded a counter-revolutionary by the Soviet Politboro and banished into exile in the Urals.

“Pasternak Provocateur, Pasternak Provocateur.” The Congress of the Communist Politique fell into chaos. For years Serge’s disappearance had been a scandal among the Parisian intelligencia yet Gide and Malraux chose to ignore his cause.

“Criminel, Criminel, Criminel,” André Breton led his band of Surrealists in a charge up the center aisle onto the stage where he held the Pasternak Manifesto above his head, waving it back and forth. “Criminel, Criminel, Criminel,” they shouted.

“No Da-da, No Da-da, No Da-da, No Da-da,” the Social Realists answered them back.

Pasternak tried to speak into the microphone raising his voice above the noise of the hall, “I live in the Gulag, Victor Serge lives in the Gulag!” Pasternak tried to be heard, “We are dying in the Gulag!” He screamed.

“Provocateur, Provocateur, Provocateur, Provocateur,” he was answered. Writers were standing on their chairs pumping their arms like train whistles in the air. The Congress du 1935 was in shambles.

“Criminel, Criminel, Criminel,” the Surrealists waved their Manifestos like little Red Books.

“No Dada, No Dada, No Dada, No Dada,” they were answered. The building shook. All of Paris came alive. Malraux had forgotten to mention these details of the story.

“The second Congress is planned for Madrid next year,” he said at our meeting in the Dingo. “After the victory in Spain has been secured. That of course is why I have asked you here. Le affaire de aeroplane is complicated for France, Devlin. This morning Blum and I met with the Spanish and it has been finalized. France will provide the shipment, but as I explained to Broz, there can be no French pilots in Spain. That is untenable. There is too much risk.”

Malraux laid opened his briefcase. It contained the details on a fully outfitted French air squadron. “They will be yours Devlin. Your squadron. Your command.” I would be given the lofty title of Commander of a new Spanish Air Squadron. “There will of course be no official French recognition of your position. Broz will be your administrator. He will provide you with everything. That has been agreed. It will be done through Broz and the Spanish.” Malraux ordered Champagne and we toasted our success. “I envy you Devlin. It would be an honor to serve in your command. To the day I join you in Madrid, Devlin,” he said. “To the year of triumph.” Malraux was I believe sincere in his praise.

The moment he left Jimmy Charters came and sat beside me.

“I have underestimated you, Jake Devlin. You never were just another American writer on the continental tour,” Jimmy said. “You are citizen worthy of the Quarter. You have livened up a Saturday night.” Jimmy nodded toward the bar. “Do you see those two fellas in the black suits at the bar? They’re KGB.”

“Can you be sure?” I asked.

“There is no such thing as a Russian tourist in the Quarter. I wouldn’t mistake KGB,” Jimmy smiled. “It gives the Dingo a reputation, a solid backbone. You’re developing character, Jake Devlin. Don’t mind that they gave Iris a few sontime. She told them what they wanted to know. She thought it was an honor, you and Malraux, you can understand,” Jimmy leaned toward me. “You are a marked man now, Jake Devlin. You keep it up and I’ll pose with you for the photo on the mirror wall. That is no small thing. Look at him turning,” Jimmy nodded toward the bar.

It was Viktor Karpov. He stood and headed for us. I have never understood why they had chosen Viktor Karpov. In the Russian elite, after Stalin came Beria, Malenkov, Khrushchev and A.A. Zhdanov and Viktor Karpov was a confidant to that inner circle. The year before he had been named to the Directorate of KGB Foreign Operations. Broz was in charge of the International Brigades but ultimately Viktor was more powerful. He reported to the Politboro. Why had he been assigned this duty? It was a mystery. Jimmy excused himself as Viktor approached.

“You’re not surprised are you Devlin,” Viktor said. “I was waiting my turn. We thought it would be better if the invitation came from Malraux. You and he think alike.” Viktor took his place along the banquette. “And Broz was worried about our problem. You can understand.” Viktor ordered a Vodka from a passing waiter. “Malraux knew I was waiting.” He lit a cigarette. “You were not my first choice, Devlin, if that pleases you, but we are both professional. The French admire you. They are romantic. What is it to me? All of you have no choice but to come to us. Broz, Malraux, even Rothstein. None of you has a choice in the end. It is the way life is divided.” Viktor laid out a map of southern France. “This is Toulouse. This is the airfield. And this is Barcelona Devlin. A four hour flight. I trust you can manage.” He looked me in the eye. Viktor never tried to mask his obsessive hatred for me. “I believe you will see it through, but once in Barcelona you will be on your own. Broz will not protect you there. We will both return to form. A risk you must be willing to take.” I had many other enemies, KGB as well, who chose not to personalize their hatred as did Viktor Karpov. But his threats were to be taken seriously. He was an accomplished murderer.

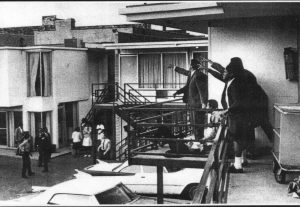

FRANCE. Paris. June 21-25, 1935. Writers Congress for the Defense of Culture.

From right to left: Writers Paul NIZAN (FR), Henri BARBUSSE (FR), Ilya EHRENBOURG

“I have already agreed to this mission, Viktor,” I said. “You have no reason to doubt me.” Viktor completed the terms of the arrangement.

“Once you cross the frontier Devlin, you never know what will be on the other side. You’ll be starting over again in Barcelona. There will be no French, no Rothstein and no Broz. You will be alone. It is a consideration. There are others who are equally qualified. Please. Do not feel rushed. You can take time before you accept. We all have our jobs to complete.”

FRANCE. Paris. Writers Congress for the Defense of Culture. French writer André MALRAUX, , Goncourt Prize in 1933 for “La Condition humaine”, is fighting against

You can find Victor Harwood’s interview with Regis Debray at http://smokesignalsmag.com/7/?p=1699 . At the time of this Paris interview in 1989, he was the Publisher & Editor-in-Chief of New York Writer magazine, a short lived but influential crossroads between the literary and commercial worlds of publishing. He is now head honcho of Digital Hollywood-Media Summit (http://digitalhollywood.com/), an even more influential crossroads between the technological-entertainment worlds.

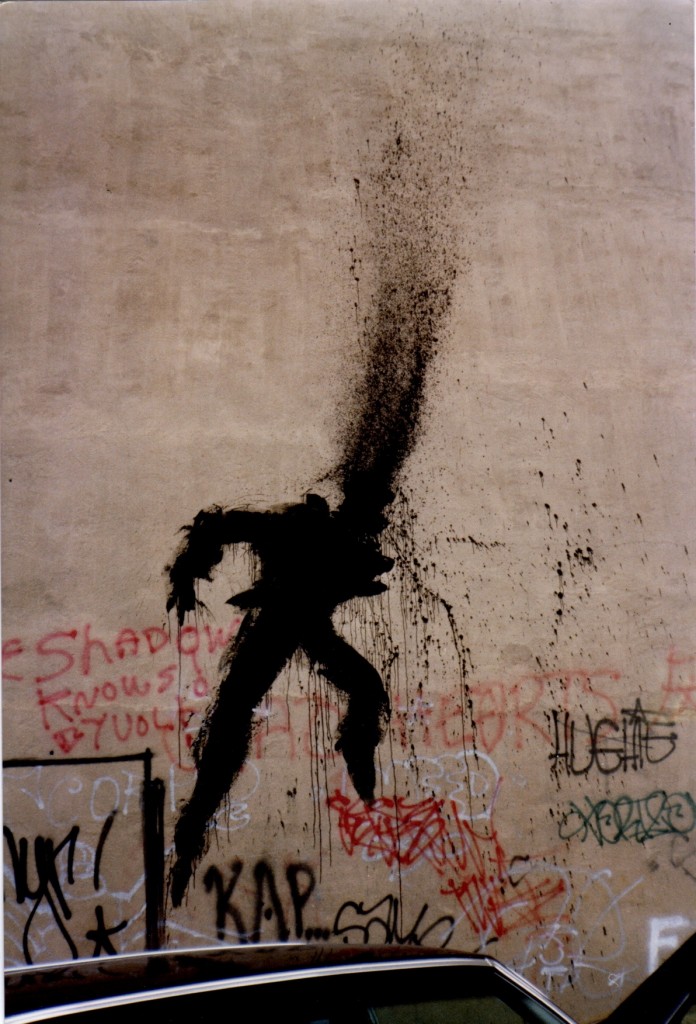

photo David Seymour 1935

photo David Seymour 1935