A

ROBERT ALTMAN FILM?

PART I: The Interview

ROBERT ALTMAN FILM?

PART I: The Interview

El-A. History is the first thing I notice in the Big Enchilada, especially when looking up in the hills after a wild all night ride on the Red-Eye Special. It will take me at least a week to get rid of my New York minute energy, and grease up for a La-La-Land lobotomy before doing a long awaited interview with Robert Altman.

In the meantime, I have a schedule: Alamo to the Santa Monica pier, first stop. I get out, luxuriate in the rays, take in the vitisphere, start identifying with homeless beach bums, and romantically hear Janis Joplin & Jean Paul Sartre singing on my personal soundstrack, Freedom’s (just another word) for what you do with what’s been done to you. . . And then rationalize my guilt over the homeless with a at-least-they-won’t-freeze-out-here shrug. The moment the thought comes into my mind I realize that since Disney malled over Times Square as part of their master plan to turn the whole planet into a theme park, there are no more authentic seedy plots or visible street people left to write about in the Naked City, and instantly I wonder if the Big Mouse arranged for all Manhattan’s homeless to be picked up and shipped to L.A. in the middle of the night, when no one was looking?

A million questions, a busy mind that won’t let go of the last straw that busted the camel’s hump. . . I’d like to be able to not take this stuff personally, but until I look up in the hills, until I realize this is the real west, brother, the true blue vision of the shandies who created the biz glaring back at me from the mosque of James Dean, I can’t breathe. Griffith Park Observatory, for those of you who may be confused by the astounding mix of visions meditating out of the hills like a pack of pure breed mongrels intrabreeding all the old strains back to the original roots of dirt, stares back at me.

The influences are so dear here. But let’s not shuck ourselves, I came for gold, like all the rest. Instead, I get what I need, get what I deserve, get the mirror where one side, or one coast, looks at the other. And this is what I saw. Or what saw me:

I was running. All of us were. From the past. Towards the future. Hurdling the present and calling it process. The moment. The now. As the act itself is lost in an incredible labyrinth of hustling dreams.

Call it generic for now. Just like Altman, all of us on this junket are shooting for the stars, to be stars, to look up at the stars and mainline some sort of perspective on the state of our insignificance as we reach out for meaning and strive for self-love. This New York minute just won’t let go, will it?

But this is not abstraction here. It’s prospecting. Digging up the spiral inside Altman by going into the bowels of my own nightmares to make repairs on the past so I can operate on generic time when I finally sit down with the great auteur. My lack of plot is deliberate. Voice is my engine, until it’s time to structure the adaptation. Right now I’m not reevaluating the dream for you, for me, even for Altman, as much as reevaluating the role of writer-director in recreating the dream.

In the canyon below me, el brujo es un animal. Listen to the bray, the cry of kids stripped from the tit of their nanny reverberating through your brain: I tell myself, all possibilities are not your possibilities, motherfucker! Some flavors are deadly. Some colors merely stick out their tongues, refusing to blend in with the environment.

For three days, four at least, I hide out up in the hills, waiting for Altman to see me, but get no word. I tell myself: Listen to the sounds of the day turn to night, but don’t try to identify them. Look at your hands, stare at your hands in a waking state. We built civilization with these hands, but let’s not go overboard applauding our creation. Then I say, “fuck philosophy,” and go out to do some long overdue meetings.

Hello, sunshine, put on shades. Put down top. Put up or shut up. Or shut up. Or shut up. . .

The first stop is lunch. (Don’t let anybody ever tell you otherwise.)

Alone. By myself. Honing my pitches for the meetings ahead, and at the same time going over Altman’s film history, just in case, today is the day I get the call to interview him: Elliott Gould looking for cat food to feed his starving cat in The Long Goodbye Fades In to my mind. Then I hear the PA announcing tonight’s movie in Mash, and suddenly see Harry Belafonte finishing his sandwich and licking his chops in Kansas City. . . For a moment I actually taste the sandwich and feel like Chris Penn secretly watching Lori Singer strip and jump in the pool in Short Cuts… Short Cuts was and is the L.A. I see and feel like I’m in when I’m out here, and like Altman, I feel the alienation of the sprawl without the shroud of Carver’s sad desperation. The emptiness is more existential than that, almost like a fine line of cold blue sweat running down the base of the spine as the temperature soars into the mid 90s, even before noon, while you slog along the Freeway from one meeting to the next.

On the soundtrack, somebody laughs out of context, but nobody feels the heat.

Though I’m inside, bathed in AC & neon, outside the sky is still moving. Clouds roll up into the hills like marshmallow shrooms about to be toasted by the Santa Ana. I feel like McCabe without Mrs. Miller, in somebody else’s opium dream.

On the screen itself, our (Yrs Truly) protagonist orders a Burger Chump. Without the cheese. But extra onions. Double sauce. Then feels fried. Totally blank. Completely empty in the pit of my stomach. But this space ain’t zen, buffs, it’s an old familiar twitch I thought I ditched years ago when I split this scene fo’ mo’ indie pastures.

Confession Time: Once upon a time ago I had to get out of this place, or check into Pitchaholics Anonymous. . .and now it suddenly dawns on me, I’M BACK!

And surreality is all around me. . . The man at the table next to me, for instance, asks his friends: “Is it possible to be all the same and all different and still mistake the clones for our doubles, and yes, vice versa too?”

I know I’m in Californ-i-A now!

Then, as if plugging into my dream, the man tells his friends he met Altman once. And of course because it is a dream, Altman related a dream to him in the dream. In the dream Altman related in the dream, he was the director of a movie, but he knew it was a dream, so he knew he couldn’t be the real director. (*) “I don’t know what this movie is really about,” Altman said. “I think I’ll find out in time. People will tell me what it’s about, and then I’ll agree and I’ll say, ‘Oh yes, that’s what I had in mind.’ Some of it’s calculated, but most of it’s done intuitively, or instinctively. It’s just something that occurs to me. I don’t know what my real reasons are. I keep the camera moving pretty much, and a lot of people, they’re more used to it now. But back in the 70s, when I started doing that, people got very irritated. They said, ‘You zoom-lens too much.’ I was trying to do it with the zoom or moving around a lot, and they said, ‘That’s not the way to make pictures.’ It was new then. Now it’s more common, and the old method of shooting is more Masterpiece Theatre. What we’re trying to do now is hide more than we’re trying to show, because the audience sees so much — they see everything — and I’m trying to make them bend their necks a little bit. I like to have a sort of obstruction in front of things so the audience feels they’re at the back of a crowd, and they want to be in on what’s going on there. ‘Did I miss something?’ they’ll wonder. Sitting there in their seats, they should feel that they have to be alert.” And so does Altman. Just then, a wise man from France shows up in his dream. A very imposing man, he approaches Altman on the set of an airport and tells him he is Godard, and orders him to get on the plane. In the dream, Altman is terrified that if he looks directly at Godard he will get on the plane and the plane will crash; but he is equally terrified that if he looks directly at Godard, Godard will yell, “Cut!” and he will miss his plane.

“A very sophisticated dream,” the man at the next table concludes, “but utterly meaningless.” Without staring, without gawking, out of the side of my eye, actually, I catch a glimpse of the man, who is looking for a question to salvage his soul. The man doesn’t know what question he is looking for, but he has a feeling that the 12 acolytes gathered around him will provide it. It being the catalyst for knowledge he knows he knows, but can’t remember. There is despair in his voice, as he urges, “Come on, children! Come on! Ask me! Ask me questions! Senility is descending upon our business. Don’t act senile! Completely senile already!” Which is when I recognize him: Galloping Guru to a whole generation of screenwriters negating the negation in the desert of formula Studio pictures, the guru’s name to many in the know has become synonymous with the business of screenwriting itself.

Partly it is the state of the business itself that gives the guru despair, but mostly his despair is personal: he himself won’t have enough time left to pitch the scripts he has to write, much less write them. . .Not hard for me to relate to, but if you’re a screenwriting guru, and supposedly have the power and connections to pitch whatever you want to pitch to whoever you want to pitch it to, and you can’t remember the inciting incidents of your stories, you must feel more like a guu than a guru. I can see it in his eyes — he wants so badly to be able to move everybody at the table closer to the epiphanies he has talked about in his classes, merely by sitting there and reciting the seven basic plots, but at this point he can’t even remember the names of the seven basic dwarves.

His old teacher said something to him about structure once, but he can’t remember what the formula was. Without actually saying it, he gives the impression that his old teacher is toast. Which is why he thinks if he is asked the right question it will dislodge a resistance in him — and though he has no real turning points in his stories anymore — he will at least be able to step-by-step bluff his way through the plot line.

“Why,” a young woman asks, “can’t you use your powers to recall what your stories are?”

“My method of recall takes as much time as the original event,” he confesses, suddenly catching me looking at him out of the corner of his eye. “To breakdown a story that happens over a 10 year period into a 90 minute film will take me 10 years. And I don’t feel I have that much time.”

He turns and stares directly at me. “To search for a question might be a quicker method, because it would contain the crucial quality of the unexpected.”

I open my notebook, turn the pages until I reach the game plan for my first meeting. “Number one,” I read to myself, then look over at the guu and his enthusiastic primies, push away from my lunch, and stand up. Before packing up and heading to my first meeting I take one final look at my notes, and look over at the guu, and repeat outloud, “What’s in it for me?”

Though that question was more for my own focus than for the guu’s benefit, there’s no denying that it has obviously become the question of the times, as well as the universal log line of the business at hand, as my first meeting synchronistically will show. My first shark, an old time shark from Studio City, swam his way up to Producer from the same lowly sewer of screenwriting I’m still swimming in at the moment. From that humble position he was invited to join a pack of young hyenas lunching on the three-picture Development deal of an aging wildebeest, and faster than you could say “Sammy Glick,” was in the driver’s seat. He not only knows all the tricks of the trade, he is a trick of the trade. “You’re gonna get fucked on the first one,” he avuncularly explains to me. “You’re gonna get fucked on the second one too. Then you’re gonna get fucked on the third one. By that time, if you get that far, if you keep your mouth shut, they’ll think you’re a good fuck, and want to fuck you again. That’s your goal, to be a good fuck, until you don’t feel like getting fucked anymore, and decide to become one of the fuckers.” He pulls a cell phone out of the built in holster in his Armani, and says to me, “I’ve got another meeting now. So make it count.”

When you’re making the rounds as a screenwriter, the pitch training goes something like Three sentences, baby: High concept. Low concentration. Or no deal, Charlie Chaplin. By this time all the true hot lickers, the genuine tongue slingers of yonder yore are sucking up on Lithium milkshakes and saving their legerdemain to take one last lap in the fast pool before it gets drained. I’ve played this game myself, but mainly as a Script Doctor for somebody else’s bacon, treading water, while all around me shark bait was bleeding all over the bottom line for a chance to be eaten.

Now it appears to be “my turn in the barrel,” as they used to say back in Memphis, preparing to pitch what the late great Poet Laureate of low life, my old correspondence buddy Bukowski, once labeled, “That Big 60s novel we’ve all been dreading.” After I repeat Buk’s log the first time, I realize my tongue is going to need a rotator cuff operation if I can’t come up with (1) “a teenage Dirty Dozen,” (2) “a geriatric Big Chill,” (3) a black & white good guys versus bad guys soap opera filled with enough elements to bend spoons into the third eyes of Studio Executives at the same time it promulgates the drool for another Beverly Hills Copout.

“Hello, Donnie-babe,” my catcher in the rye sings into his baby-Bell. “I’m glad I caught you. Is there any word yet? Have we got a Go or no? I don’t have to tell you that my contradictions runs out at the end of the year, and while this has been a very positive stagnation here, you can let Jeffrey know that I’m aware of the possibilities of the situation and am open to making a move, if we can work out the structure of the deal.”

He puts his hand over his instrument and turns to me. “So sell me, bright boy.” Then shakes his head up and down and squeals into the mouth piece, “Of course Allen’s part of the deal! He’s my partner, we’re brothers, he’s a genius and. . . Jeffrey thinks he’s dead weight?” He smiles. “Well, I’m not crazy enough to tie an anchor around the project. As usual, he’s right. I was just being sentimental.” He puts his hand back over the cup and says, “It’s the Seventh Inning stretch, and your audience is starting to leave the ballpark. Gimme the hook. Sell me the package. Chop-chop. What’s in it for me, baby?”

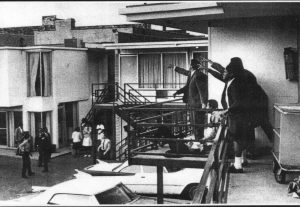

“Listen,” I begin, “the story is not that simple, but the rolls are so fat they’ll kill for ’em. Centered around the still unsolved Martin Luther King assassination, harsh reality and pop mythology collide when a young Bulgarian Yogi — who the last of the living old bluesmen believe is from Uranus — shows up in Memphis looking for Elvis. Strung-out reporters on the trail of “the Big Story,” government hitters chasing a reporter because he knows too much about what’s really happening in Vietnam, carpetbagging yankee ethnomusicologists searching for “the real blues,” visiting mobsters out to fill a J. Edgar Hoover contract on Dr. King, liberated ladies celebrating their right to free love, campaigning Presidential candidates, stoned hippies, black revolutionaries throwing off the shackles of Uncle Tomism, and the assassin himself, stalk the canvas of 1968, and turn the various McGuffins swirling around the assassination into an edgy blues Ragtime chasing the white whale of conspiracies until they change both the face & body of American culture forever. . .

“Whatta you think?”

He holds his hand over the receiver, and says, “Sounds like an Altman film to me. What else you got?”

A dog story. I have a dog story. A very shaggy (musical) dog story. And a girl gang movie. An end of the world detective story. And a modern Western set in Australia. . .in order to capitalize on the tax break. And a road movie, a buddy picture, a horror film, a cult classic, in the tradition of. . . Babe Ruth. Who struck out 1,133 times. Keep swinging. That’s what I keep telling myself. Over & over & over again. . .as I feel the old pitchaholic sickness taking me over again.

I’m operating on automatic now, ignoring the slick glued to his phone like two lovers in the heat of the moment, and in that moment in my mind I’ve already started pitching Altman “that big 60s novel we’ve all been dreading“, while still in the middle of working up questions for an interview I’m starting to feel really nervous about. Of course pitching someone a project in the middle of interviewing them is not exactly considered kosher. But this is a sickness, and by now I’m an addict.

Just admitting that makes me feel better, though not necessarily smarter. I’ve worked on this story for close to 20 years, so I certainly want it shot the way I wrote it. . .I make a mental note to ask Altman at the beginning of the interview just how important the script actually is to him. His reputation for changing scripts makes writers who admire his work very uncomfortable, to say the least.

Right now Altman is in the editing room, finishing up his interpretation of John Grisham’s first original screenplay, The Gingerbread Man. And he’s not taking outside calls until he’s finished. I can’t say I blame him, but of course I’ve been chasing him for over nine months to do the interview, and for whatever it’s worth I’m on deadline now, and running out of time.

To his credit, Altman’s always treated the universe out in Hollywood as if it were Washington, D.C. Publicity is a necessary evil. Doing Press a bad joke. The Studios, of course, operate very much like the Pentagon. At any given time, the majority of all working screenwriters are metaphorically building wings for bombers that the Generals have already declared obsolete. The nightmare Altman painted so vividly in Michael Tolkin’s The Player was by no means an exaggeration, though strangely enough Altman has said about his most successful post Nashville film, (*1)”I would have bailed out of The Player even after the first cut of the film. All the time I never thought we were doing anything. I was experimenting, but I never had any great confidence in The Player.” Maybe this — my attempt to interview him and pitch him at the same time — is a sequel he can feel more comfortable with? I definitely feel like I’m in a Robert Atlman film right now, so maybe I am, and maybe this is the script he’s diddling with.

I’d heard a lot of stories I want to check out with Altman about his relationships with screenwriters. . .For instance, at their first meeting he warned California Split screenwriter Joseph Walsh, (2*)”You know I’m supposed to be your mortal enemy.”

“Why?” Walsh asked, “What have I done?”

“Well, you’re a writer,” Altman said, and writers have a real thing against me. They seem to think I take their work and do what I want with it.”

“Oh, do you?”

“I do what needs to be done.” Altman said.

(3*)Ring Lardner Jr., who won a Best Screenplay Oscar for Mash, said, “I visited the set only once, leading Altman to call out, ‘Hey, somebody find the script! Here comes the writer!’ Despite the joke, he kept pretty close to the scenes as written, encouraging improvisation mainly in a couple of scenes between Donald Sutherland and Elliott Gould. . .letting them rephrase the lines in their own words, sticking to the main content of each speech and the purpose, construction and resolution of the scene. . .I think the reason it worked was we had the same attitude toward the material. . .Altman made many changes in the script, and most of them were, in my opinion, beneficial. If I had known at the time I was presented the Oscar that Bob was not going to get the one for Best Direction, I would have made a point of acknowledging his collaboration. . .”

Those words — “I do what needs to be done” — haunt me. I know from my own experience directing a couple of guerilla indies that never got finished because of the financing falling apart in the middle, the first thing I learned in the heat of the action was that you do what has to be done. And a lot of the time what has to be done means completely changing the script. Even if the script is your own. I don’t like it, but I know it’s reality. Brutal fucking reality. . .

Keep swinging, is what I tell myself. Tell myself over and over for the next three days, the next 15 meetings, lunches, poolside breakfasts, dinners, Dodger games, until it all becomes the same. Until I finally get the call from Altman.

Well, not Altman, exactly, but Altman’s assistant. It seems like Altman suddenly had to go to New York.

He’ll talk to me when he gets back to L.A. . . .

This seems like the signal on more than one level to Stage Left, and duck out of the flow. No matter what they grew up as, most working American artists today of any consequence have embraced some kind of Buddhist philosophy to live by, and I’m no different, but if I have religion that religion would be called Always Keep Your Bags Packed, so within an hour I’m on my way to the airport.

On the way, I stop and duck into the new Burger Chump on Franklin, and to my surprise spot the guu sitting there alone, without his disciples, slowly munching on a Burger Chump. The image of one lone screenguu eating a solitary hamburger fills me with despair. Is this a film by Altman? Or a short story by Carver? I can’t tell the difference anymore.

I want to tell the guu I have the answer to the question he’s looking for, but I still don’t know what the question is, so instead I grab a burger to go.

On the way to the airport I picture my hands. There is nothing on the San Diego Expressway but my hands. And they’re in a hurry, a big hurry. All grabbing, squeezing, twisting their way to a rendezvous with the Red-Eye Special.

In line to check my bags through, I finally looks up from my hands. The passenger in front of me immediately starts talking, and begins to relate a dream to me he had about me: And of course because it is a dream, I relate a dream to him in the dream. In the dream I relate in the dream, I am the director of a Robert Altman film, but I know it’s a dream so I know I can’t be the real director. Just then, the real Robert Altman shows up in the man’s dream. A very imposing man, with a Buffalo Bill goatee, he approaches me on the set of an airport and tells me he is Altman, and orders me to get on the plane. In the dream, I’m terrified that if I look directly at Altman I’ll get on the plane and the plane will crash; but I’m equally terrified that if I looks directly at Altman, Altman will yell, “Cut!” and I’ll not only miss the plane, I’ll never get an interview either.

Long after the deadline for the interview has gone down, I finally get Altman on the phone, and relay the dream to him. After listening silently until I finish, he says, “A very sophisticated dream.” Then pauses, and concludes, “but utterly meaningless.”

(1*) Patrick McGilligan’s Jumping Off The Cliff

(2*) Patrick McGilligan’s Backstory

(3*) Pret-a-porter book (*)

originally published in Creative Screenwriting Vol 4, #3, 1997

COMING SOON

A ROBERT ALTMAN FILM?

PART II: THE SEQUEL

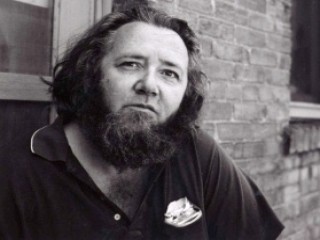

photo by Richard Skidmore

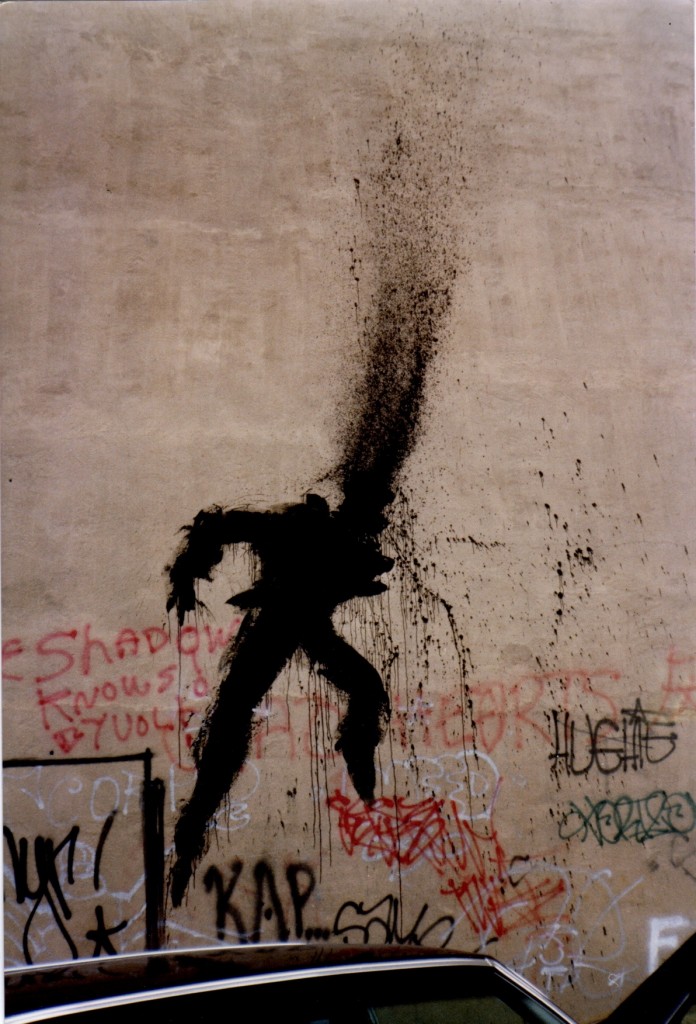

photo by Richard Skidmore