Alan Greenberg’s

ROPE-A-DOPING WITH MUHAMMAD ALI

ROPE-A-DOPING WITH MUHAMMAD ALI

I follow boxing. Not the sport as much as the anthropological event that each fight is. In August of 1974 I was twenty-three years old, living alone in Manhattan, reading in the Sunday Times about a bout in Zaire between the unbeaten young heavyweight champion, George Foreman, and the aging former champion, Muhammad Ali. It was a promotion of enormous proportions run by a rookie named Don King, and was spectacularly conceived to overshadow the fight itself, the outcome of which was seen as a foregone conclusion. The Olympic gold medalist Foreman was regarded as invincible, a raging beast of suitably monstrous physical proportions, having won all but one of his fights by knockouts of the most brutal sort. Ali, on the other hand, was in decline, having lost to Joe Frazier and Ken Norton. But he was more popular than ever, especially in Africa, and this government-sponsored festival was to be his glorious Last Hurrah.

To me this was alarming. At age ten I had met Ali, then Cassius Clay, in Miami, when he was a rising contender, and like so many fans I was fascinated by his extraordinary mental and physical gifts, and his undeniably wild charisma. Then the courageous stand he made against the U.S. Government in opposition to the Vietnam war ratcheted up the love and admiration bestowed upon him by far more than the boxing community. Even in defeat, his losses seemed somehow redemptive—rising bravely from a crushing knockdown to lose on points to Frazier, then fighting almost a full ten rounds with a severely broken jaw against Norton. However, this rite of passage in Zaire seemed frightful, a sacrificial slaughter of a beloved icon. I even dreamed about it: I saw Ali backed into the ropes and hit with a Foreman blow to the ribs so murderous it made Ali scream. So the Sunday Times piece got me thinking.

I decided that Muhammad Ali needed to see me.

This was urgent. I gathered my cameras and tripod, borrowed a Toyota from a neighbor upstairs, and headed west. Three hundred miles later I reached Deer Lake, Pennsylvania, near Amish country, and soon found a cluster of log cabins that was Muhammad Ali’s training camp. The champ’s assistant, Gene Kilroy, told me that Ali was on the road promoting the fight; since he was scared of flying, later round midnight he would arrive home by bus and head straight to bed. I grabbed dinner in town, then returned to the camp after ten o’clock and waited near the driveway for Ali. Precisely at midnight a Greyhound-like bus arrived with its lighted signboard reading “Fooling Around”, and with Muhammad Ali at the wheel.

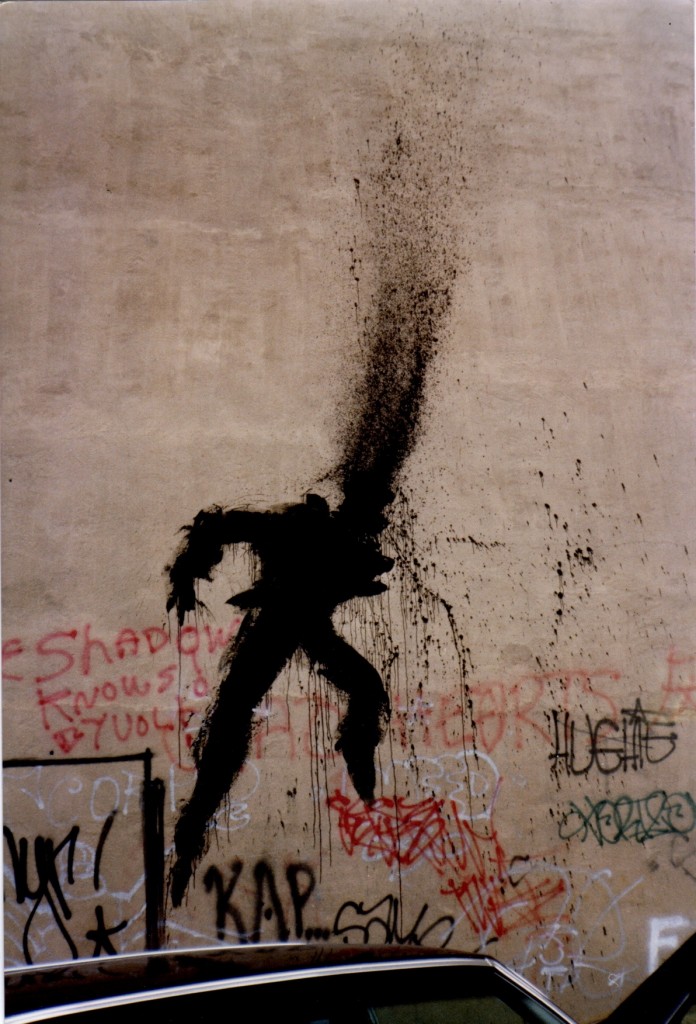

With my bagged tripod slung rifle-like from a shoulder, looking like a pug-loving Mark David Chapman, I stepped from the shadows to the open door of the bus. Wearily Ali stood up and stared down at me. I introduced myself and handed him a letter that a friend, who worked at Paramount Pictures, had asked me to give him. Instead of taking the stranger’s letter and excusing himself, the massive man graciously sat down on the steps and carefully read it. Then he read it again. But now, to my dismay, once he looked up, something seemed to be wrong—the great Ali was angry.

“I ain’t no dog that jumps at a bone,” he said softly.

Immediately I explained to him that I had nothing to do with the letter except deliver it to him sealed. And coming from Paramount Pictures, I presumed I was also doing Ali a favor. But I was wrong. Like a slavemaster talking down to his boy, a Paramount executive had written to Ali that the company had chosen to cast the handsome boxer in the lead role of its upcoming production, “Mandingo”, based on a book best described as a pit of racist trash. The mogul told Ali—told him, not asked—to call his office as soon as possible. Shaking his head, the proud Muslim sat on the steps of his bus and quietly discussed four hundred years of African-American history with me, speaking reasonably, often eloquently. After more than an hour of this I apologized on behalf of my friend at Paramount, suggested that maybe some day I’d return with my cameras, wished him luck against Foreman and got back into my borrowed car. As I was about to turn the ignition key, a huge heavily-muscled hand grabbed my bony shoulder.

“Don’t go,” Ali muttered. “You’re different.”

He and his wife Belinda put me up, and early the next morning I waited as instructed by Ali for him to finish his roadwork. He showed up in grey sweats and combat boots and sat on a pile of firewood, motioning me to join him as Kilroy handed Ali several pages of publicity material for the fight. He pored over page after page as I focused my camera on him, waiting for him to look up. He paused to read and reread a particular page with eyes widening, then finally he raised his head, his face a mask of relief. “ I’m as big as he is,” he uttered wondrously, realizing for the first time that he was the same size as the mythically gargantuan Foreman. Up to this moment The Greatest, The Louisville Lip, the man who made bragging and taunting into performance art and naïve literature, hadn’t thought he stood a chance to win.

“I can beat this guy,” he whispered with conviction. Ali gazed into me, searching for something.

I took his photograph.

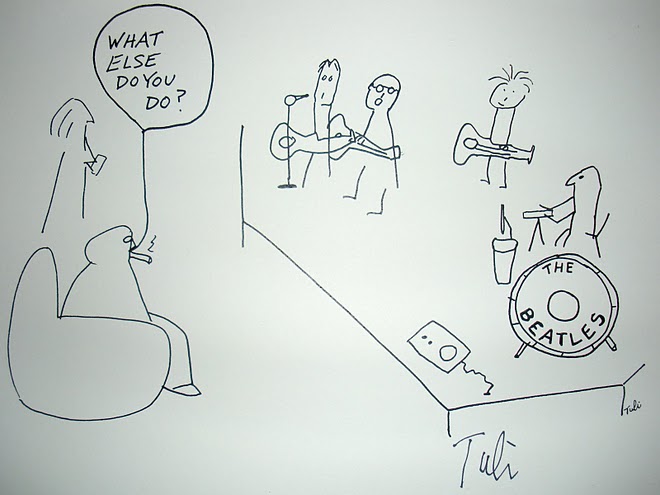

The afternoon was spent in the gym. I watched Ali spar with hired fighters who changed every three rounds, always leaving him with fresh opponents to test his stamina. But now they were testing more than his stamina; they were also testing his strategy. For three hours Ali was in the ring sparring, and the entire time he never threw a punch. Instead he laid on the ropes, elbows in tight, occasionally pawing with his left to give his sparring partner an opening for a body shot. Round after round after round he let himself be bludgeoned, fighter after fighter pounding him without letup. Was this the sluggishness of a faded ex-champ? Was this really Muhammad Ali? When he finally stepped down I asked him what he was doing in there, having never once thrown a punch.

“I’m gonna get that sucker so tired of punching me he’s gonna fall flat on his face,” Ali replied. “He’s gonna be too embarrassed to get back up.”

And so the “Rope-a-Dope” was born, not in the ring in Zaire, but in a gym in Pennsylvania.

At the door to his locker room I snapped a quick photo of weary, perspiring Ali, and he cast me a sharp glance of disapproval while wrapping himself in a white terrycloth robe.

“You ever seen a picture of me after a fight, all sweaty and bruised and ugly?” he asked, knowing I knew my boxing. I told him I never had. “That’s ‘cause I’m a Muslim. And we don’t let ourselves be seen that way. So don’t bother none with that picture you just took—I got something else in mind.” Then Ali paused and lowered his voice.

“I want you to take a picture of me naked,” he revealed.

I was ready and willing to oblige him. Inside his locker room I sat on his massage table with my camera trained on its subject, who busied himself removing the vitamin jars and empty juice glasses on the end tables before sitting on the sofa. A few test shots were taken, then Ali laid back across the sofa, and without hesitation he untied his white robe—only to stop when someone knocked on the door. It was Kilroy, who told him that a woman he knew had stopped by with a friend.

Ali sat back up as the woman he knew entered and sat with Ali, her friend following. When the second woman sat beside me on the massage table I realized that she was the most stunning black beauty I had ever seen. As did Ali. For fifteen minutes I photographed the roused fighter flirting with her as their powerful sexual attraction shook the walls. Ali’s eyes were as wide as they were whenever he saw an opening for a knockout blow; she feinted with a smile, her eyes luring him in. Ali saw the trap, and abruptly—almost rudely—ordered the two women out of the room. He waited, listening for the door to shut. Then in a grave voice he addressed the younger man.

“Always remember, Alan—women are evil,” he said.

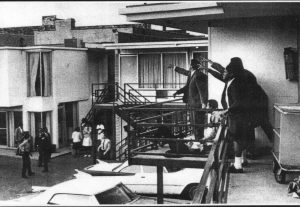

The evil visitor he was referring to was named Veronica Porsche. Cut to a year later, when every newspaper worldwide displayed a front page AP wirephoto of Heavyweight Champion Muhammad Ali, in Manila to fight Joe Frazier again, meeting Filipino President Ferdinand Marcos with “his wife” on his arm. When his wife Belinda saw this photo of her husband with Veronica Porsche, she flew to Manila and confronted Ali the day before his bout, keeping him up all night as she threw his suitcase out a broken window and trashed his room. The boxer was sleepless and distracted when he faced the fierce warrior who had already once defeated him. There was no Thrilla in Manila for Ali, despite his thrilling victory. After Belinda filed for divorce, he married Veronica, with whom he had daughter Laila, the future undefeated women’s boxing champion.

That night I tried to assuage my disappointment with the aborted photo opportunity. Within minutes I realized there was another way to photograph Muhammad Ali in the nude. I decided to take a portrait of his famously iconic white fighting shoes. At midnight I slipped into the locker room, grabbed the shoes, then set them in the dark atop a large boulder with “Joe Louis – The Brown Bomber” emblazoned on it. It was hard to see beneath the moonless sky, but I managed to slip a wallet into place to put one shoe on its toe, then I set the large tongue flapping. Through the viewfinder I made out the number “13” inside the ankle of the other shoe, and the word “Everlast”, and lastly a slender black hand reaching down from the shadow between the two shoes.

Unable to see the shoes until the flash burst, I risked but one shot. The portrait was perfect: Muhammad Ali, for the ages. Au naturel.

| Boxing Editor, Alan Greenberg is a writer-photographer-screenwriter-filmmaker, whose work includes HEART OF GLASS (which Rolling Stone called “The best book on the making of a film ever written”), LAND OF LOOK BEHIND (an award winning documentary centered around Rastafarian culture in Jamaica during Bob Marley’s funeral) and LOVE IN VAIN (the story of legendary king of the Delta bluesmen Robert Johnson, which was the first unproduced screenplay ever published by a major house as literature. In the near future Smoke Signals, will premier his long hidden feature film, the dark comedy, LIVING DREAMS. |