Martin Torgoff’s

RED DIRT MARIJUANA

an excerpt from BOP APOCALYPSE

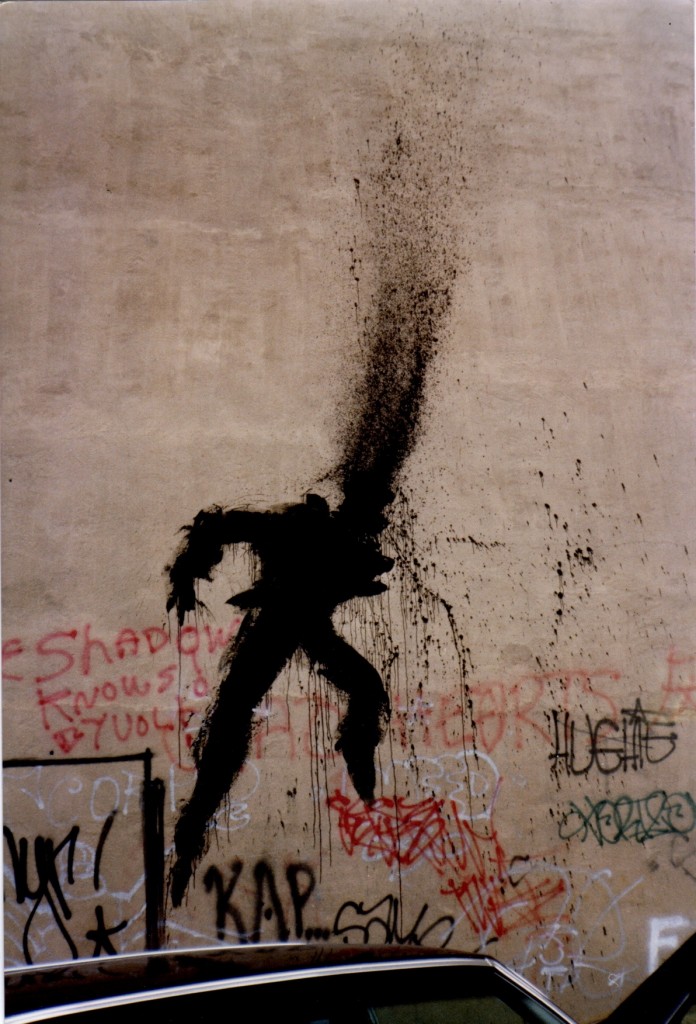

RED DIRT MARIJUANA

an excerpt from BOP APOCALYPSE

There was something about the way the cow was laying on the ground that piqued Terry Southern’s interest and made him laugh. The animal was just lying out there on its stomach, that hot summer day, its head on the dry scrub brush, a dazed, loopy expression on its face.

There was something about the way the cow was laying on the ground that piqued Terry Southern’s interest and made him laugh. The animal was just lying out there on its stomach, that hot summer day, its head on the dry scrub brush, a dazed, loopy expression on its face.

Young Southern had gone out to his cousin’s farm in Alvarado, Texas to make a few dollars picking cotton. After that he and his cousin and C.K., a young black field hand, were on the way to go fishing, when they first noticed the milk cow stretched out in the Johnson grass.They walked over to it and Terry gently kicked at it, trying to get it up. The cow protested, but refused to budge. Examining it more closely, Terry noticed the animal had very heavy-lidded eyes and seemed awfully content. That was when he saw the half-uprooted green plant in the midst of the mesquite bushes and a patch of dwarf cactus. “What’s the matter with this cow?”

“Oh, there’s nothing wrong with her,” C.K. told him, “she’s just had some of that loco weed over there.”

Southern’s cousin thought the weed was toxic and wanted to call a veterinarian immediately. But C.K., who’d pulled the plant out of the ground, was looking at it admiringly. “Yeah, this is mighty good. This is red dirt. This is pretty dang strong. . .I guess we’d better burn it,” C.K., ever the dutiful field hand, said. But on the way back to the house, he kept going on about the plant, shaking his head and saying, “this is mighty fine gage,” and couldn’t really bring himself to accept burning it. “Oh, well,” he finally decided, “I guess we’ll dry it out and sell it.”

The year was 1936—the year of the Texas Centennial. By no stretch of the imagination was it a common time or place for a twelve-year-old white boy to be smoking marijuana with a black field hand, but Terry Southern was anything but common, even at the age of twelve.

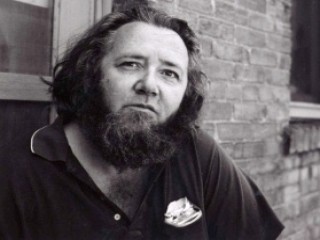

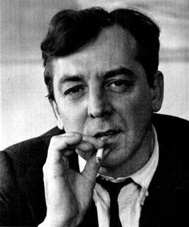

“We went back to the barn and dried the stuff out, and that’s when C.K. twisted up a few and turned us on,” Southern recounted, tipsily sipping on a glass of cognac in a suite of the Wyndham Hotel in New York. It was the winter of 1993, not long before the writer, who had suffered a stroke and was teaching screenwriting at Columbia at the time, would pass away. “That first time I was very apprehensive,” Southern continued. “Coughing a lot. But intrigued enough to work at it the second time, holding it longer in my lungs. My father was a pharmacist, so I knew a bit about drugs, but marijuana was a totally unknown substance in this part of Texas for white people. So this was a totally new and unrelated experience.”

By the time Terry smoked his first joint in 1936, marijuana had come to symbolize much more than a cheap high. Public concern over cannabis, or “Indian hemp,” in the United States had originated in the Southwest and had been steadily increasing since the end of the First World War, when it had appeared on the Texas border as “Rosa Maria” and black cavalrymen stationed along the border were known to indulge in its use.

“After that incident, I went back to Fort Worth. There was this black guy that delivered big chunks of ice for the refrigerators. He would come every day and I was supposed to pay him and give him his two dollars for the last week, and when I came back with the money I guess he thought he was going to have a little time because there he was smoking his joint. I came out of the back porch screen door and saw him doing it, just the same way that C.K. had taught us—‘Gotta suck it in with a lot of air!’—and he would make this, like, viper sound as he did it . . .

“I guess I surprised him. He saw the way I was watching him and said, ‘Weeel, now, don’t guess you’d be innerested in this sort of thing. . .”

“‘Oh,’ I said, ‘is that loco weed?’”

“He laughed, and said, ‘Well, I don’t know if you’d call it that’—you know, still holding his breath in—‘we call it gage.’ Of course, being a Texas kid, I was still very much in a segregationist mindset, but I asked him if he had any to sell. ‘Well, I ain’t no pusher,’ he said, ‘but I’ll give you some.’ And so he gave me a couple of joints, and there I was, holding for the first time. . . . I remember this wonderful mischievous feeling came over me, and I had a friend and invited him over, and we smoked. By that time, you could say I was actually getting a good buzz, and all these strange and funny things were starting to happen.”

The marijuana had no immediate outward effect on Terry’s life, but as he started smoking with more frequency, he became increasingly more interested in exploring the Central Track area of Dallas. “It was the part of the city called Nigger Town,” Southern pointed out, “and as soon as I was able to make that connection, I realized that smoking was something that I had in common with black people. And yet, I have to say, they completely altered my life.”

Along with the life-changing cross-cultural impact of experiencing the black neighborhood of Depression-era Dallas, the effect of marijuana on Terry Southern was most discernible in the long-term development of the way he looked at the world. An avid reader as a boy, he had already begun to write stories when he was eleven. Right around the time he encountered marijuana, he became interested in rewriting stories by Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edgar Allen Poe because, as he put it, “they never seemed to me to go quite far enough . . . I made them get really going.” It was an unusual hobby for a Texas adolescent during the 1930s, to say the least—self-appointed rewrite man for some of the most intense and gothic authors of the literary canon became trademarks that would eventually make Terry Southern one of the foremost American satirists of his time. By the 1960s he was internationally known for a style of writing characterized by outlandish moments and a skewed but devastating critique of the values, mores, and politics of conventional middle-class American society.

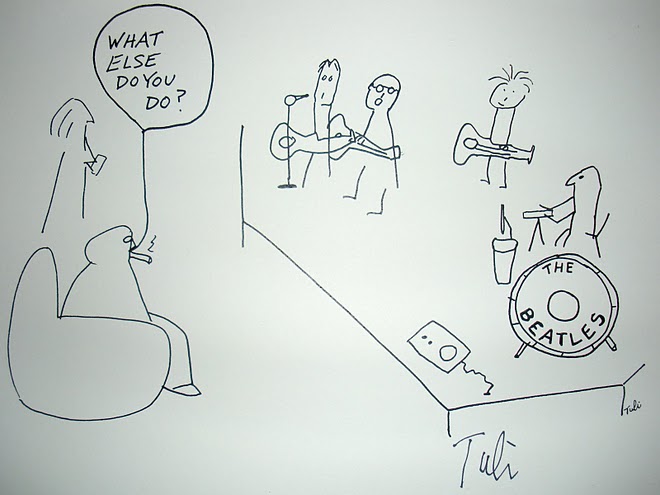

Not for nothing did the Beatles place Southern amidst the assemblage of personalities on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in 1967, right there in his dark ditty-bop shades. By the time Southern came to write the celebrated campfire scene for Easy Rider, and give Jack Nicholson his big break with his character’s wiggy digression about UFOs & Venutians (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L7GJ018Avgw), any tracing of the origins of his satirical sensibility as a writer pointed right back to the sight of a stoned cow lolling comically in a barren and dry Texas pasture that led to the first few times he smoked pot.

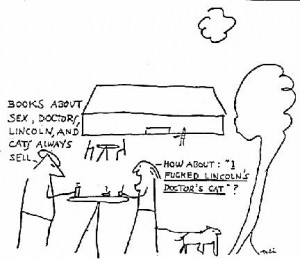

“How come it’s against the law if it’s so all fired good?” asks the boy to C.K., the field hand in the classic short story that opens Southern iconic collection Red-Dirt Marijuana.

“They got to have it against the law. Shoot, ever’body git high, wouldn’t be nobody git up an’ feed the chickens! Hee-hee . . . ever’body just lay in bed! Jest lay in bed till they ready to git up! Sho’, you take a man high on good gage, he got no use for they ole bull-crap, ’cause he done see right through there. Shoot, he lookin’ right down to his ver’ soul!”

“By the time I wrote that story, twenty years or so after I’d smoked marijuana as a boy, marijuana was already becoming part of a step-by-step breaking away from the mainstream values of the culture,” Southern reflected. “For a certain kind of individual smoking it, this one isolated high began to have a growing impact on one’s insight. Some people were going to smoke it and get into a light kind of music high, but others were going to see right through to the very heart of the corruption of the system—to how the political parties were both locked in by the same interests and money and lobbyists and how dirty it all was, and how it was all virtually meaningless and quite absurd. So in that respect, marijuana had the potential to be a very seditious thing indeed—the end of everything as we knew it in the good old USA. But it certainly didn’t start out like that in that one year, 1936 to ’37, when it all seemed to start—this gigantic rumpus about some little ole weed growing wild . . . right there in a tumbleweed field in Alvarado, Texas.”

#

© 2017 – Martin Torgoff

Bop Apocalypse (ISBN: 978-0-306-82475-3)

Da Capo Press

Excerpted from Bop Apocalypse: Jazz, Race, the Beats, and Drugs by Martin Torgoff. Copyright © 2017. Available from Da Capo Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. For further info: contact Raquel Hitt at Da Capo Press [email protected]

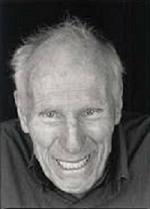

A noted pop culture historian and Contributing Editor at Interview, Martin Torgoff has covered the rise of drug culture in America as a writer and television producer, through documentaries like Planet Rock, The Drug Years and Elvis’56, and books like Can’t Find My Way Home, The Complete Elvis and the ASCAP- Deems Taylor award winning American Fool.

Bop Apocalypse (ISBN: 978-0-306-82475-3) is the story how drugs originally entered the DNA of American culture through the birth of jazz in New Orleans, the first drug laws, Louis Armstrong, Mezz Mezzrow, Harry Anslinger and the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, swing, Lester Young, Billie Holiday, the Savoy Ballroom, Reefer Madness, Charlie Parker, the birth of bebop, the coming of heroin to Harlem, the rise of the Beats, and the interest of at least one 12-year-old white boy in Alvarado. Texas.

This excerpt from Bop Apocalypse is based on an interview Martin Torgoff did with Terry Southern, the major bridge between black humor and beat aesthetic. Terry recalled how on one hot Texas summer day, this 12-year old white boy who was once him, discovered loco weed. Then learned how to smoke it. Evolutionary acts which inadvertently expanded his consciousness, opened his sense of relativity about the world and changed his point of view about black culture. All of which, approximately 20-years after that day, inspired him to write Red Dirt Marijuana,

Now Dig This, the Smoke Signals Interview with Terry Southern, where he talks about almost everything else but Red Dirt, can be found on this site at http://smokesignalsmag.com/7/?p=2862