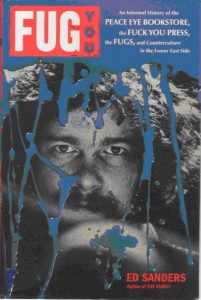

excerpt from

Rudolph Wurlitzer’sThe Drop Edge of Yonder

Rudolph Wurlitzer’s

The Drop Edge of Yonder

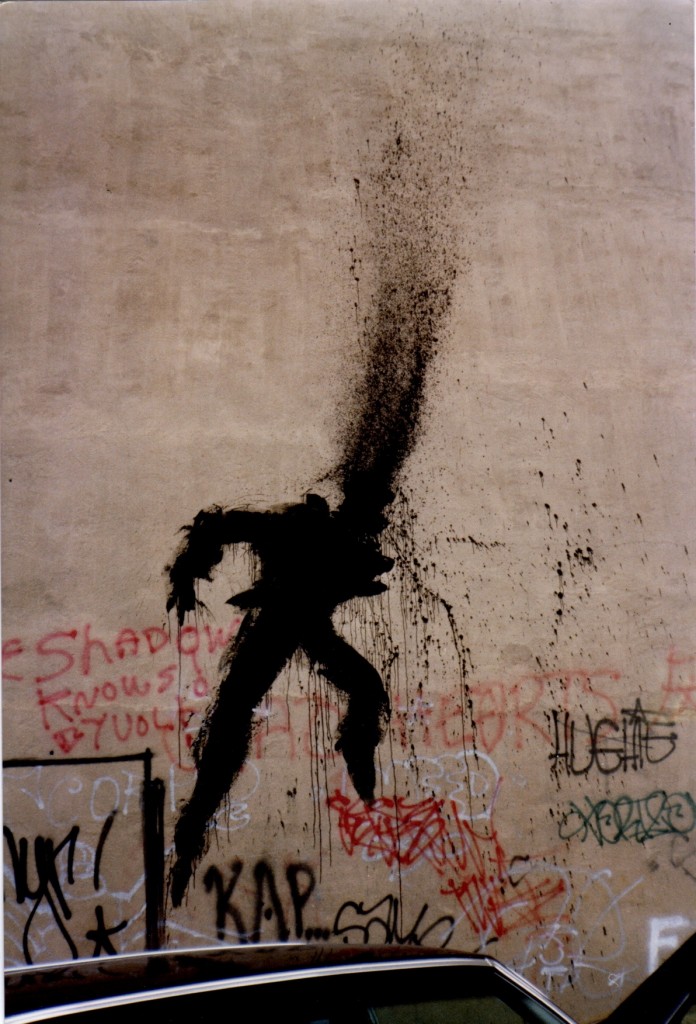

When the whaler sailed into San Francisco Bay six weeks later, half the city was in flames and black soot-filled clouds sagged over the water like shrouds. Through the flames Zebulon could see the smoky silhouette of the shore and the hills surrounding the city where thousands of tents and canvas-covered shacks were sprawled around iron buildings that had been shipped in from the eastern states. The Captain and the Portuguese crew were afraid to set foot on land, convinced that the entire West Coast had been seized by a biblical conflagration; a disaster brought on, they had no doubt, by the godless scum of the earth who had deserted families, traditions, and religions to rush off to the gold fields. The ship remained anchored in the bay for six days until a squall drenched the last of the fires. Finally, fears suspended, if not relieved, the ship made its way towards a long line of wharfs, passing along the way hundreds of deserted vessels.

Zebulon disembarked into a furious crowd of hawkers yelling offers for supplies, whores, jobs, flop houses, peep shows and business deals. Now that his hooves were planted on the land, he promised himself that he would never embark on a ship again. Here was the Promised Land. Here was freedom from the past, a chance to break loose. He let out a loud mountain yell, nearly causing a horse and wagon to bolt off the dock. Never mind Delilah or Hatchet Jack or being trapped between worlds. Never mind what his Ma or Pa or anyone else had said or thought or done. From now on whatever hell awaited him would be of his own choosing.

He walked off the dock and shouldered his way into the first saloon he came to-three stitched-together army tents supported by empty crates and scrap iron. The bar was fashioned out of three wooden planks, each twenty feet long, propped up on empty whisky barrels. Every inch was jammed with newly arrived immigrants and prospectors: Kanakas from the South Seas, Hawaiians, Cubans, Peruvians, Chinese, Russians, as well as all sorts of Europeans and foot-loose Americans. The only subject in the saloon was gold: Where to find it, how to mine it, how to spend it.

He drank through the rest of the afternoon and into the evening, not moving except to relieve himself in a long ditch outside the tent. The more whisky he consumed, the more he thought of Delilah, as if his exhilaration had given her an open invitation to invade him, and the more he tried to shut her down, the more present and haunting her spirit became.

When he finally staggered outside it was dark and a soft mist was drifting over the waterfront and the hills. Not knowing where to go and preferring higher ground, he climbed a hill towards a collection of shanties and tents thrown together out of canvas, potato sacks, old shirts, and whatever else was available. When the mist turned to rain followed by a violent downpour, he crawled into a lean-to. Inside, two men in red long johns sat near a crude stove made out of barrels, playing poker on a wooden crate. The older man’s head was as smooth and shiny as a bullet. When he looked up at Zebulon, the tattoo of a sperm whale bobbed across his Adam’s apple.

“Come far, partner?” the man asked.

Zebulon sank down by the stove. “Far enough to know better.”

“You can say that again,” said the younger man. He was rail thin, with a long bushy mustache drooping over his sunken chin.

“We’re lucky to have shelter,” the older man said. “We threw together this pile two days ago in the middle of a rainstorm. Me and my boy aim to stay here until we put together a stake. Then it’s hallelujah and off to the gold fields.”

“I’ll pay for the night,” Zebulon offered.

The younger man looked at his Pa, as if waiting for a sign. When his Pa nodded, he threw his cards on the crate. The only card face up was the queen of hearts.

“I’ll be goddamned. Lookee here. That old queen keeps floppin’ up like a high-priced floozy.”

“Don’t mind my boy,” his Pa said. “He ain’t won more’n two hands all night. Him and me are Christians from the Church of the Holy Rapture. We’re Pennsylvanians and proud of it. We work for the Lord and share what we have and don’t gamble for money or drink hard liquor. We expect those we work and live with to help themselves to everything we got and we’ll do the same.”

“Fair enough,” Zebulon said, and passed out.

When he woke the following morning the lean-to was empty. His money had disappeared, along with his boots, his Colt, and Delilah’s necklace. All that remained was half a pot of cold coffee.

Outside, a raw wet wind blew off the bay. People were moving about in front of the tents and shanties, cooking breakfast and speaking in foreign tongues. Beneath the hill, beached on the shore like wreckage from a tsunami, were the hulks of schooners, brigs, paddle steamers, steamships, ferries, scows and yawls. A few larger vessels had been converted to temporary saloons, others transformed into hotels or warehouses. One of them was The Rhinelander. All three of her masts were gone and a yellow and red sign was painted across her stern: RHINELANDER HOTEL BEDS 75 CENTS.

He drank the rest of the coffee; then bound his feet with rags. Avoiding the still smoldering embers, he stumbled down the hill past the charred remains of what had passed for shacks. When he reached The Rhinelander, his feet were bleeding and his pant legs were hanging in strips from his waist.

The deck was jammed with prospectors and refugees from the fires, all of them guarding their supplies. Not recognizing any of the crew or passengers, Zebulon went below.

Captain Dorfheimer lay spread out on the bunk of his cabin in a silk bathrobe, staring at the ceiling where a freshly painted galaxy displayed hundreds of stars circling around red and green planets.

Slowly, as if each cracking joint was causing him agonizing pain, the Captain gathered himself up and stumbled over to the chair behind his desk. Holding his head in his hands, he stared bleakly at Zebulon.

“How I fear and loathe the past when it arrives unannounced.”

“I’m here to settle our account,” Zebulon said.

Dorfheimer sighed, massaging the back of his head. “If only that were possible. My officers and crew have deserted me for the gold fields. Every last one. Left me to rot. Don’t misunderstand, business will pick up. I have to hang on. Serve decent food. Provide fresh sheets. Then they’ll pay double and I’ll sail away from this cursed land, never, God help me, to return.”

He opened his desk drawer, removing a page torn from a newspaper.

“Thanks to Artemis Stebbins, you’re famous from Mexico to Alaska. My God, if I had known about the wild and violent crimes you’ve committed, I would have had you thrown overboard.”

He handed the article to Zebulon, who glanced at it, pretending to read, then handed it back.

“Allow me,” the Captain offered.

“No need,” Zebulon said. “It’s all lies.”

The Captain folded up the newspaper and returned it to the desk drawer.

“Where are they?” Zebulon asked.

“Baranofsky ran into some trouble in a Spanish town south of here. I heard he was in jail. Stebbins will know about the woman. He hangs his hat at the Busted Flush, a cafe down the street.”

“Are you going to settle up?” Zebulon asked.

The Captain shook his head. “Obviously you didn’t hear me. Your passage and trip across Panama was paid for, which was far more than you deserved, given all the trouble you caused. Are you aware that there’s a five-hundred-dollar award posted on you, dead or alive? I should have you arrested.”

“Settle up,” Zebulon said, picking up a letter opener from the desk.

The captain stumbled over to a chest. Pulling out an officer’s uniform he threw it at Zebulon. “My father’s. A vice admiral in the Kaiser’s navy. It will confuse the bounty hunters and vigilantes. Now leave. Go away and never come back and I promise that I will never mention you to anyone, not even to myself.”

Zebulon changed into a tight-fitting jacket with blue epaulets. Then he put on black pants that were six inches too short and had a broad red stripe running down the side, followed by knee-high boots. The whole assemblage was topped off by a cockaded admiral’s hat and long sheathed sword.

Zebulon laid down the letter opener, took the Captain’s pearl-handled revolver from the half-open drawer of the desk. Looking into a mirror, he blasted his image into flying shards of glass. Another bullet blew open the handle of a small wall safe.

After he removed seventy dollars in gold coins, a string of black South Sea pearls and a gold-plated pocket watch, he shoved the revolver into his belt and yanked Dorfheimer to his feet. Dorfheimer shut his eyes, expecting the worst. When Zebulon embraced him, the gesture was so unexpected that the Captain collapsed on the floor, weeping and gasping for breath.

When Zebulon appeared on deck, he was greeted by shouts and applause from the assembled, everyone believing that Dorfheimer had been shot because of his overpriced accommodations and rotten food.

At the end of the gangplank, Zebulon turned to offer a salute to Dorfheimer, who was staring down at him from the bridge.

“I will see you in hell,” Dorfheimer shouted.

“I’m already in hell,” Zebulon replied. Tossing the admiral’s hat into the harbor, he walked down the dock and into the city to find Delilah.

**************

Delilah stood on a wooden platform at the back of the room, wearing a low-cut red dress. Her eyes were half-closed, her face caked with thick makeup. The newcomers in the room had never seen anyone like her, or experienced a voice so penetrating and melancholy. As she sang, two fiddlers and an accordion player provided enough rhythm to keep her on course.

Think they’ll marry white man preachers

Heads thrown back to show their features

Ha, ha, ha, Black Town gals!

Zebulon noticed Stebbins sitting alone at a table, rocking back and forth as she repeated the last line to wild applause.

His eyes narrowed as Zebulon sat down opposite him.

“I heard you been writing lies about me,” Zebulon said.

Stebbins filled up his glass and pushed it towards Zebulon. “It’s why I’m here: to satisfy the public’s insatiable hunger and curiosity for frontier lore. And you, my friend, rank with the very best, thanks to my adventurously inflated prose.”

He looked at Delilah. “Our friend has contributed more intimate details about you than any scribbler could wish for. How you forget to take off your boots when engaging in the act of love, how you become violent when you lose at cards or billiards, or how you obsessively invent your past. All touching human fallibilities which help make a story appealing and accessible.”

Zebulon walked over to Stebbins and lifted him off his chair.

“Extry! Extry!” Stebbins shouted, struggling to free himself. “Read all about it! Deranged mountain man goes berserk. Kills reporter for spilling the beans about his outlaw past. Read about his squalid love affair with an Abyssinian courtesan and a Russian count.”

Zebulon dropped him and sat down as Delilah launched into another song:

Oh, what was your name in the States:

Was it Zebulon or Ivan or Stebbins or Bates?

Did you flee for your life, or murder your wife?

Say, what was your name in the States?

I’d comrades then who loved me well,

A jovial, saucy crew;

A few hard cases, I’ll admit,

Though they were brave and true.

Whatever the pinch, they’d never flinch,

Would never fret or whine-

Like good old bricks they stood the kicks

In the days of ’49.

“A word of advice,” Stebbins said, pouring a drink. “Choose an alias. Especially in San Francisco. Anything but Admiral Doom. Admiral Death has more punch. Think about it. After all, death is what people out here know about. Death and gold. Never Doom. Doom is the last thing they want to hear about.”

They both turned to watch Delilah as she looked over at their table and began another song:

So I’ll pack my clothing

And in search of him I’ll go.

I’ll cross the wide wide ocean

Through storm winds and snow.

And never shall I marry

Until the day I die.

So I’ll die broken-hearted

For my old mountain boy.

She sang the next verse in Portuguese, or maybe it was another song altogether, stretching out the vowels and ending each verse with a melancholy wail that traveled slowly up from her belly to her throat. By the time she finished, several men were openly weeping, unable to control their buried longings and fears. One man shot his pistol at the ceiling. Others stood on their chairs and cheered, throwing coins and nuggets on the platform, which were scooped up by the musicians who took half for themselves before they handed the rest to Delilah.

Zebulon watched her weave slowly through the crowd, as if her fragile and weary body was struggling against a strong wind.

“How amazing!” she said to Zebulon as she sat down. “You’ve joined the German navy. And become an officer as well. Although your uniform does need some repair.” She poured herself a drink. “Is it true that the Germans have plans to take over California and Oregon, as well as Mexico and Alaska? Or is that the English?”

He stared at her, shocked by how much weight she had lost and the deep lines around her mouth and eyes.

“I know,” she sighed. “I don’t bear close inspection. A girl’s joie de vivre can so easily vanish when she has to sing for her supper.” She shook her head. “And what about you? You don’t look so well yourself.”

She looked across the room where a waiter, no more than four feet tall, was maneuvering his way towards them, holding a tray over his black gnome-like head.

“I was hoping someone had stepped on him,” she said wearily, as the dwarf placed a bottle of whiskey and two glasses on the table.

Nodding at Zebulon, the strange dwarf spoke to Delilah in Portuguese.

“Toku is confused about you,” she said to Zebulon. “I don’t know why. Why don’t you tell us, Toku? We have no secrets at this table. Very few, anyway.”

The dwarf pointed at Zebulon.

“Tell your friend to stay away from games of chance,” he said with a clipped English accent, “or he’ll end up in a ditch. If you know what I mean.”

“I don’t know what you mean,” she said.

He shrugged and picked up his tray. “You know very well what I mean.”

“Do you plan to keep our appointment?” Delilah asked.

“When I am ready. Not before. Do you have any idea how difficult it is to find three guinea pigs? And not just any three guinea pigs. They all have to be the same age and color. And then there’s the state of the moon, and various other elements that you have no knowledge of. If you ask me once more, or even look at me in the wrong way, you will find yourself talking to a stone wall.”

He turned and walked back across the room like a drunken sailor navigating his way across a rolling deck.

“A friend of yours?” Zebulon asked.

“He used to be some kind of pet or court jester for the Captain of an English ship,” she explained. “When everyone went off to the gold fields, he stayed behind. When he heard me sing, he told me that he had known me in a past life. He’s African. Every time I ask him what tribe he’s from, he tells me something different-Baule, Bwiti, Pygmy. Whatever he is, he has strange powers and sees things other people can’t. I suppose I have an addiction for second-sighted people.”

She started to gulp down a shot of whiskey; then thought better of it. Standing up, she steadied herself on the back of her chair; then slowly made her way out of the room.

He knew he should let her go, but he followed her anyway, keeping out of sight as she stumbled out a side door into an alley ankle-deep in mud. Once he thought he had lost her only to have her reappear and turn into a courtyard.

He stood in the shadows as she knocked on the door of a wooden two-story house with narrow windows protected by iron bars. Once again he felt presented with a choice. In the past, he had set his course by his instincts and certain signs; a shift in the wind, a campfire on the horizon, tracks in the snow. But now he felt separated from his instincts or any sign. He only felt fear.

When the door opened and Delilah disappeared inside, he continued down the alley to the waterfront. He could ride south to Mexico, he thought. But he had already made that journey. And now there was a bounty on him. Wanted. Dead or alive. He would be better off trying his luck in the gold fields. He had taken enough from Dorfheimer for a decent stake. Or he could go on the drift, up to Oregon or Alaska. He knew how to exist hand-to-mouth. Riding fence, rounding up cattle, busting horses-none of it mattered as long as he was free and unknown. He looked out at the harbor where anchor lights were blinking from hundreds of ships. The whole place was on the gallop with orders to fill. If one direction didn’t work out, there would be ten more.

The hell with her, he thought; then returned to where he had left her. He rolled a smoke in the courtyard, then stubbed it out and knocked on the door.

A Chinaman opened the door, staring at him through spectacles the size of bird’s eggs. A long black queue fell past his waist, and his reed-like body was covered with a silk maroon robe.

Zebulon followed him into a claustrophobic low-ceilinged room lit by sputtering candles. In the dim half-light he made out a couch and a row of armchairs filled with shadowy figures that he figured were women for hire.

“You want?” the Chinaman asked and snapped his fingers.

A pubescent girl no more than fourteen rose up from a chair, clacking towards him on wooden sandals, a loose yellow shift hanging from her bony small-breasted frame.

“Young delight,” the Chinaman said. “Small buds. Like peaches. Good for the heart.”

His voice was oddly precise, as if he had learned English from a missionary.

“I’m lookin’ for a woman,” Zebulon said. “A mix. Not white or black. A long tangle of black hair.”

The Chinaman shook his head. “Delilah not for sale.”

“Not to buy,” Zebulon insisted. “To talk.”

The Chinaman smacked his hands together as if killing a mosquito. “Twenty dollars. But no touch. Only smoke.”

After Zebulon paid he followed the Chinaman into a back room that smelled of burned chestnuts. A low table held a lamp and several bowls filled with black opium paste. Emaciated men lay on their sides on narrow tiers of bunks, their heads resting on polished blocks of black wood. Delilah lay on a lower bunk, inhaling a long bamboo pipe lit by an old Chinese woman wearing a black high-necked dress.

“Are you dreaming me?” she asked with a smile as he lay down beside her. “Or am I dreaming you? Or are we being dreamed by someone else?”

She sucked at the pipe; then slowly exhaled.

“Where’s my necklace?”

It took him awhile to remember. “Stolen.”

“I’m not surprised. Everything else has been stolen or taken from me. The only thing left is to invest in loss…. Do you ever ask yourself who belongs to whom? …Or why? Or why it is that most people prefer to rush towards their death rather than step out of the way?”

The old woman offered him a pipe; then held up a long wire with a smudge of opium resin on the end. After he lit the resin, she motioned for Zebulon to inhale. He repeated the procedure several times until he turned on his back, staring up at the ceiling.

Delilah’s voice drifted over, like a leaf floating on a slow moving river. “If she rubs your feet, you’ll float in the air.”

He wasn’t floating. He was a frog pinned beneath a giant thumb; until he moved a finger back and forth in front of his eyes.

“I betrayed Ivan,” Delilah said. “And I betrayed you. But if you had stayed on the ship, Ivan would have killed you. He tried it before. In New Mexico. Or was it Turkey?”

He remembered being a small boy and watching an eagle feather float down from a blood-red sky and then land gently on his head.

“It’s a sign,” his Pa said after he shot the eagle. “I’m damned if I know what it means. Only that its’ better not to think about it.”

“Are you aware that dark spirits are searching for us?” Delilah asked. “For Ivan…. And for me…. And for you…. That’s all they know how to do. They hunt for prey and when they find it they swallow it, as if they intend to take on who they kill.”

They lay side by side, legs and sides barely touching, smoking and slipping in and out of each other’s dreams. He felt suspended somewhere between earth and sky.

“Or nowhere at all,” he said to the fingers rubbing his feet.

The thought was pleasing, that of going nowhere at all. Never to move on. Never to hunt. Never to leave one place for another. Or one woman for another.

Her voice found him again. “After San Francisco, we rode north, Ivan and I… So wild, so many rivers to cross and guns and horses. Ivan found more gold than anyone would ever need. Then he lost it all in a card game. He lost me, too…. So many men…. I was the only woman for a hundred miles…brutal men…I never wanted to see you again…. You’re wanted for murder…stealing horses…robbing banks…. A very dangerous man. When I saw you in that Mexican hotel I knew you were hunting me…. What I didn’t know was that I was hunting you as well.”

He curled up like an animal inside a burrow, his arm over his eyes, his heart beating as if he was imprisoned inside a trap.

An old woman wrapped inside a man’s button-down canvas jacket was bending down, holding a pipe, inviting him to inhale, to disappear into another dream….

“Men came from everywhere to hear me sing,” Delilah was saying…. “Then Ivan found me again. He always does, you know. And then he leaves.”

Someone was playing a flute in another room, and a woman was singing about love and a journey that never ends.

“Now Ivan will die. When he abandoned me in London, an Englishman took me in. A singing teacher. An aristocrat…. I have a certain weakness for aristocrats. So distant and unobtainable…. He taught me opera…. How to speak and read English…. Every time I tried to leave him, he became very cruel.”

Across the room the Chinese girl was massaging the singer’s feet, or maybe they were his own feet. Her scent made him feel as if he was lying in the middle of a garden. Or a cemetery.

“Ivan found me making love to the Englishman,” she went on. “He wanted to kill me. He had been in prison. In Russia…. They tortured him…. There are scars on his cheeks from cigarette burns. He’s not a count, you know…. He’s a spy and a scoundrel and a businessman. He smiled when he shot the Englishman through the head.”

He wondered if Ivan had shot him in New Mexico. Or had it been Delilah? Or someone else? Was he, in fact, dead, and dreaming his life and how it had been, or might have been? He was on a journey. He was sure of that. A journey that he was unable to track, without a beginning or end, with no boundaries to guide him.

Her voice drifted back to him: “When my parents died, I lived with my grandmother…. She was over a hundred-and-fifty years old…. I had come to her in a dream before I was born…. Because I have mixed blood from different races; she taught me not to become trapped in any one world…but not to live between worlds…. That is my fate in this life…to learn how to die…. In my previous life I-…. I can’t remember…. She said I had to leave everything that I was attached to…even her, in order to be in the world but not of it…. When a Portuguese slaver killed my grandmother, I lost faith in God…I forgot everything she taught me.”

In the middle of the night, or the next day, he opened his eyes.

Delilah was staring down at him.

“Do you know who I am?” Her voice was a faint whisper, as if shivering through the tops of trees. “I am the one that hunts for other worlds in the darkest night, the one who lives inside dreams within dreams. Because I have lost my way, I am a hostage to all that floats between the worlds. Including you.”

He followed her past the lost dreamers curled up on their bunks and then down a narrow winding alley, stepping around buckets of waste tossed out of windows, abandoned mining equipment and Argonauts passed out on soggy wooden planks.

On the waterfront, they collapsed against a pile of grain sacks stacked against an overturned wagon, falling asleep with their arms around each other. In front of them thick layers of fog spread slowly over the harbor’s armada of abandoned ships and the rows of river schooners lined up gunwale to gunwale along the sagging wharfs.

They woke to a blaring trumpet and a pounding drum.

A dozen men wearing shiny black suits appeared through the fog, marching behind a woman in a red fez and yellow pantaloons holding up a sign announcing the end of the world and the grand opening of the Paradise Hotel.

They sat leaning against each other, their bodies swaying like hollow reeds. The night had left them empty, without any sense of urgency or any direction, free of all dreams and intentions. The fog had dissolved, and the sun was spreading rays of light across the bay. On the street, a small boy whistled as he pushed a ball ahead of him with a stick. A group of Brazilian sailors drifted hand in hand down the embarcadero, followed by a team of mules pulling a wagon loaded with mining equipment.

“I’m going on alone,” she said. “I’ll come back tomorrow and look for you in this same place. If you’re not here, I’ll know that whatever happened between us has come to an end.”

He sat watching her as she stood up, and without a word, walked away from him. When she finally looked back, he stood up and followed her to the end of the embarcadero, then along a narrow grassy path that led through stunted, windswept pine trees and thickets of wild rose bushes. Crossing a steep hill overlooking the sea, they stopped in front of a round hut constructed out of brush and torn canvas. In back of the hut, amulets and prayers written on strips of cloth hung from the branches of a towering oak tree. Six wooden statues of three-breasted women guarded the hut’s entrance. A smaller statue of a grinning monkey with a protruding belly stood behind them, the skin of a rattlesnake wrapped around its neck.

Delilah pulled a canvas flap over the hut’s opening. “Welcome to my sanctuary. But if you go in, be warned. You might not be able to come out.”

She guided him towards a circle of round polished rocks on the edge of a cliff. Beneath them long curling waves pounded on a rocky shore. As far as they could see there were no signs of life except for a full-masted schooner beating her way to the north.

They sat silently inside the circle. When the sun disappeared, she left him, returning with a bowl of water and a cloth. Removing his clothes, she piled them outside the circle, then dipped the cloth into the bowl of water and washed each part of him.

She spoke as if she was instructing a child: “You have to be clean when you stand inside the circle. Otherwise you will disturb the spirits.”

She handed him the cloth and bowl of water and took off her clothes, arranging them in a pile next to his, allowing him to slowly spread the wet cloth over her body.

They were interrupted by Toku walking toward them. He was dragging a heavy burlap sack and shaking a tambourine, and wore a patched yellow orange robe falling down to his ankles.

“I’m tired and very annoyed,” he said, collapsing inside the circle. “You could have told me how long it would take to get here. And I need to be paid before I begin. My spirits won’t work for nothing.”

“Give him ten dollars,” Delilah instructed Zebulon.

“Thirty,” Toku replied. “And they’re doing you a favor,”

“Fifteen,” Delilah countered.

After Zebulon paid him, Toku reached into his sack and pulled out three squealing guinea pigs and a curved scimitar. Squatting on his heels, he sliced each of their bellies into four sections, then poked his fingers through the entrails.

He looked up at Delilah. “You’re confused about dreaming, about who is dreaming who. Your problem is that your dreams are controlling you, not the other way around. You no longer know how to stand on the earth. Too much hanging around the Dream Palace.”

“I could have told you that,” she said

“But you didn’t,” he replied

He wiped his hands on his robe and jumped out of the circle, shaking his tambourine. Then he jumped back and squatted on his haunches, poking a stick through the entrails again.

“I see a prophecy, which is more than I expected to see, given your cloudy spirit. You will have a son, but he will never know his father. There’s something else that I don’t understand. Something about never being able to be in one place for longer than a few days.”

He pointed at Zebulon. “That will be true for you, too. Not that it’s any of my business.”

“What is your business?” Zebulon asked.

Toku flopped on his back, cackling like a chicken as he slapped the ground. “Business? My business is making business. Why else would I be in this country? One day I’ll have enough to buy a restaurant. And then a hotel. Maybe I’ll even go back to my country and invest in a kingdom.”

He took a pair of dice from his sack and rolled them over the ground, muttering an invocation in a foreign tongue.

“When you were a small boy, someone tried to drown you. Maybe it was your brother. The one who is not your real brother. Or maybe it was your father. Whoever it was, you’re living inside a big confusion. Ever since then you’ve been afraid of water. Water means death to you and until you die to who you think you are, you won’t be able to live. Make sense? You’ll always be on the move, trying to find out who you are. Like the rest of this crazy country.”

Toku poked through the entrails again.

“Did someone shoot you in the heart?”

“I think so,” Zebulon answered. “The bullet passed through me.”

“You think so?” Toku said. “What kind of an answer is that?”

“Can we get this over with?” Delilah asked. “I didn’t ask you to come up here and talk about him.”

“One more thing,” Toku said stiffly. “Your friend is a violent man who has done his sharing of killing and fooling around. He thinks doom is death and death is doom. That’s why he wanders around like a ghost not knowing what trail he’s meant to walk on.”

Silently, he poked through the entrails; then nodded to Delilah. “You’re the same. Just passing through. That’s why you’re drawn to each other and why you will never be together. Do you find that amusing? I don’t. You have to find a way to help each other so you can be free of each other. Maybe that’s what people in this country mean by love. Who knows? Not me.”

He picked up his knife and dug out a long trench. Then he instructed them to lie down on their backs, head to head. After he had covered their bodies with dirt, except for their eyes and nostrils, he reached into his sack and took out a round mask of a grinning monkey. Then he buried the mask between their heads.

“This mask is your face and the face of everyone who has ever lived. When you understand that the separations between people are illusions, the spirits will go back where they came from. Right now the spirits are angry and confused. All they care about is sucking everything out from inside you and replacing it with greasy smoke. That can be very uncomfortable if you don’t know the remedy.”

He jumped up and down on Zebulon’s chest and stomach, banging the drum and smacking his thick lips. Then he did the same to Delilah. Lighting up a half-smoked cheroot, he blew smoke in four directions, haranguing Delilah in his native language. She had no idea what he was saying as he continued to shout, more and more agitated. Finally, fed up and more than a little afraid, she pulled herself out of the trench and staggered to the creek, where she submerged herself in the water; only to have Toku drag her by the hair back into the circle.

“Oh…Ah…Ha! he cried, banging his drum and spitting into Zebulon’s face and then into Delilah’s. “Oh…Ah!… Eh!… Ha…Ho!… Ah… Ha!… Eh!… Ho!…

Suddenly Delilah dropped to the ground, rolling over like a snake shedding its skin. Zebulon fell down beside her, his arms jerking in spasms over his head as a current of energy rose violently up his spine. They remained flopping and writhing next to and on top of each other, until the energies roaring through them stopped and everything became flat and empty.

“The bad spirits have left,” Toku pronounced. “Or most of them. If they come back, I’ll need more than fifteen dollars to get rid of them.”

He put the mask into his sack, bowed to the statue of the monkey, then to each of them. “If you’re lucky, you will never see me again,” he said.

********************

|

Rudy Wurlitzer - Our Road Editor, though he usually travels incognito. Novelist (Nog, Quake, Flats, Slow Fade and The Drop Edge of Yonder, essayist (Hard Travel To Sacred Places) and screenwriter of cult classics like Two Lane Blacktop, Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid, Candy Mountain, Walker and Little Buddha, among others. http://www.rudolphwurlitzer.com/ Rudolph Wurlitzer Bookworm 2009 Interview with Michael Silverblatt http://www.vertigomagazine.co.uk/showarticle.php?sel=onl&siz=1&id=1013 |