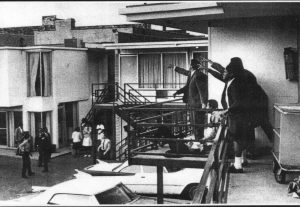

’68 Democratic Convention

excerpted from

Richard Seaver’s

THE TENDER HOUR OF TWILIGHT

excerpted from

Richard Seaver’s

THE TENDER HOUR OF TWILIGHT

The year 1968, again having no alternative, dawned on a note of mingled hope and despair. The turbulent 1960s were winding to a close — or so it seemed. In fact, the worst — or best, depending on your viewpoint and political bent — was yet to come.

The United States was still bogged down in Vietnam. What had earlier been termed JFK’s war was now Lyndon Johnson’s, and that albatross was weighing ever more heavily round his thick Texas neck. Quagmire abroad was matched by increasing resistance to that “pointless, hopeless” war at home. And the naysayers and protesters could no longer be labeled by the administration as hippies and druggies (weren’t they the same, after all?), Commies and pinkos, Beats and bohemians. Middle-class Americans were joining the marches and signing the petitions, and even American corporations — perhaps for their own venal reasons, but nonetheless — were alerting Washington to the fact that continued, unqualified support of the war was not a given.

It was an election year, and the mood of the country did not seem to bode well for the incumbent. Taking political advantage of the nation’s growing winter of discontent, voices of opposition were gathering political strength as the primaries began. One man in particular, the senator from Minnesota Eugene McCarthy, surrounded by a band of exuberant, youthful cohorts, was focusing on the folly of the Vietnam War in particular and, to judge by the polls, gaining in popularity week by week. The greatest political enigma of the moment was the carpetbag senator from New York, Robert Kennedy. Where did he stand on the key issues? Would he or would he not challenge a president he clearly loathed but till now had backed for a second term? As for Lyndon Baines Johnson himself: Would he or would he not run again? If he did, the Democratic nomination was his. But in the late months of 1967 and the early months of the new year, he had been pointedly, and eloquently, silent on the subject.

For their part, the Republicans seemed intent on nominating that all time loser, Richard Milhous Nixon, the man who had lost the presidency by a whisker — no, a shadow — to JFK in 1960, then followed up that painful loss by failing in his quest to unseat Pat Brown two years later for the governorship of California. Early in 1968, the New Hampshire primary shocked the country — and the politicians. Gene McCarthy and his youth brigade’s unexpected vote total at the Democratic primary led Johnson to withdraw from the race. The message was clear: in 1968, politics as usual was an endangered species. But even before McCarthy the Good had had a chance to savor his victory, Robert Kennedy, the Great Vacillator, made a decision: it was time to join the race. The detested LBJ was indeed vulnerable. McCarthy had shown the way, but he, however worthy, was vulnerable, too. Once the vaunted Kennedy machine revved up, Gene’s guys and dolls would be revealed as the rank amateurs they doubtless were. Tough, the cries of foul play. Be damned, the accusations of callow opportunism. There was a dynasty to be protected and prolonged. Camelot was not dead after all.

In a stroke of journalistic brilliance — madness? — Esquire magazine, sensing that the Democratic convention in Chicago might well be a historic event, invited three world- famous writers, all Published by or associated with Grove, to cover the convention: the satirist Terry Southern, author of The Magic Christian, “the author most capable of handling frenzy” (Esquire); William Burroughs, author of Naked Lunch, the nightmarish work that had propelled him from the North African expatriate drug scene to New York Times bestsellerdom; and Jean Genet, playwright, novelist, ex- convict, and homosexual, author of two long- banned works we had recently published in the United States, Our Lady of the Flowers and The Thief ‘s Journal, a man dubbed by the State Department as “undesirable”

and, as we have seen, by the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre as “Saint Genet” (take your pick). And to round out the fearless threesome, Esquire assigned the journalist John Sack to cover the convention from the police point of view. Not quite equal time, but still . . . Whether it was the publisher, Arnold Gingrich, or the editor Harold Hayes who dreamed up the idea, it was an act of inspired madness. For even Esquire, which early on modestly proclaimed that it “required no special wisdom to foresee that the Convention of the Democratic Party in Chicago was likely to transcend the limits of ordinary politics,” could know that those five days in the Windy City would turn into a lopsided mixture of theater of the absurd, Grand Guignol, and pure tragedy, into an event that the respected newsman Eric Sevareid would later term “the most disgraceful spectacle in the history of American politics.”

At seven o’clock on Sunday morning, August 18, the phone rang in our ramshackle but beloved former horse barn on eastern Long Island, where we spent most weekends. I picked up the receiver, wondering who could be calling at this ungodly hour.

“Allo. Dick Siv!re?”

My name all right, but with a decidedly French tilt.

“Jean here. Jean Genet.”

“Jean! Where are you calling from, Paris?”

“No, Canada. I’m on my way to New York.”

“Great. So you got your visa after all.”

“Not exactly. I’ll explain everything when I see you. I should be there

in a day or two.”

“Shall we get you a hotel?”

“Yes, I’d appreciate that.” Pause. “Uh, Dick. Nothing too fancy. But as

close to Forty- second Street as possible.”

“Okay. I’ll call you back to let you know where you’ll be staying.”

There was a pause. “You can’t,” he said. “I don’t have a phone here. When I get in, I’ll come down to Grove, and you can direct me from there.” I knew that Genet had no fixed abode, that wherever he went he preferred hotels, and the more frugal the better. Jail had doubtless given him a taste for the spare. He had written eloquently on the terrors of long- term convicts emerging from prison to “freedom,” described how difficult it was to adapt to the world you had dreamed of rejoining, and theorized that excons felt comfortable only in prison like surroundings. Thus his penchant for cell-like hotel rooms.

I called Barney in East Hampton to inform him of Jean’s impending arrival and to settle on a hotel.

Jean’s enigmatic remark about his visa reminded me of the story he had told me about his previous encounter with American officialdom four years

before.

In the early 1960s, several of Genet’s plays, including The Maids, The Balcony, and The Blacks, had been performed in New York to great success, and we had published them as Evergreen paperbacks. By 1964, two of the plays had been performed a thousand times, and to celebrate that twin event, the producers and Grove had jointly invited Jean to New York. Genet went down to the American consulate on the rue St. Florentin and duly filled out the necessary forms. He was then called in to the vice- consul’s office, where he was asked a number of weighty questions, the most important of which was: “Are you now or have you ever been a Communist?” To which Genet truthfully said, “No.” H e had in fact briefly been a Trotskyite, but certainly that did not qualify, did it? (I later asked Jean what he would have answered if the man had asked him whether he was a homosexual, fully expecting him to tell me that he would have lied. But Jean rarely gave you the expected. He simply said: “But he didn’t ask me.”) Whereupon the vice- consul stamped his passport with the American visa and Jean returned to his lodgings, a fairly remote Paris hotel.

A few hours later the landlady yelled upstairs: “Monsieur Jean, you have a phone call!”

Most no-star Paris hotels in those days had but one phone, down in the owner’s office. Jean did not receive all that many calls and wondered who it could be.

“Monsieur Genet,” the voice on the other end began, “this is the American consulate. “This was not the voice of the man who had stamped his passport. Genet assumed it was the man’s superior, probably the consul himself. “I wonder if you’d mind stopping by the consulate,” the man went on.

“Of course,” Genet replied. “May I ask why?”

“I’m afraid we’ve made a mistake in giving you a visa. Could you kindly bring your passport back so we can correct the error?”

Genet remembers thinking that the poor vice-consul, doubtless a semiliterate who had never read his work and had no idea what a threat Jean was to the fabric of American society, would probably be soon on his way to the U.S. equivalent of diplomatic Siberia. Visibly, the man on the phone was better read.

“Monsieur,” Genet said, “when I needed a visa, I came to your embassy to get it. If you want it back, you can come here and get it.”

There was a pause.

“You should know that even with that visa in your passport, they’ll stop you at the border,” the consul said. And with that he hung up.

After that exchange, Genet decided he didn’t want to go to the United States. Jean never knew why the reversal, but he assumed it was either his homosexuality, his status as ex- convict, or, most likely, the fact that Grove at the time was being harassed by a whole panoply of would- be censors for its scandalous publications, from D . H . Lawrence to Henry Miller, William Burroughs to, yes, Jean Genet himself.

This time, Grove decided to take the matter into its own hands rather than leaving it to the Paris bureaucrats. Barney had a relatively highly placed friend in Washington to whom he wrote several letters. The replies, when they came, were politely evasive. He would look into the matter. He would see what he could do. He understood that Mr. Genet was a writer of world stature. There were proper channels, however, as he was sure Barney would understand. Esquire, having concocted the triumvirate, seemed vague on the matter. If the threesome was reduced to a duo, so be it. Perhaps it was feeling blinded by its own brilliance, and having second thoughts. Irrespective of Chicago, we at Grove very much wanted Genet to come for our own selfish reasons. His works, both fiction and drama, had been well received and highly praised. And for once, despite the usual alarms, neither of his novels had been attacked by the censors. With Genet, there were no court cases to gobble up the proceeds.

As July waned, we had to admit defeat and inform Genet that we had struck out in Washington. “Don’t worry,” he said. “I’ll take care of it myself.” I wondered just how he would take care of it.

The next morning, Jeannette and I took a taxi from our Central Park West apartment to the Biltmore.

The cherubic bad boy’s (at fifty- seven) only baggage was a tiny briefcase hardly capable of holding toiletries, much less a change of clothes. I knew from my earlier meetings with Genet in Paris, and from talking to Bernie Frechtman, that he generally traveled light. But this light? “Did you leave the rest of your baggage at the station?” I asked hesitantly. Genet looked at me as if I were mad.

“This is my baggage,” he said with the trace of a smile, pointing to his briefcase. And indeed, for the next ten days, when we lived in close proximity and — as will be seen — in virtual intimacy, Jean needed no more than the contents of his satchel.

I had forgotten how cherubic-looking the man was. Pixie-like. No more than five feet five or maybe six. His pate was all but bald, with a small snow-white patch of hair just above the slightly protruding ears. And his eyes: pale, pale blue. But it was not so much the color that made them distinctive as the intensity with which they fixed on you. When he talked to you, you were the only person in the universe. Few people in my life have ever made me feel that way — Beckett was one — it is a rare quality. After lunch, on our way back uptown to the Biltmore, I asked Jean why he had gone first to Canada instead of directly to New York. I wanted to get the lowdown on the visa. Jean responded by reminding me of the fiasco at the American consulate, saying that he had decided never to make that

mistake again. “I’ll tell you the whole story,” he said. “But you must promise not to tell Esquire. Otherwise they may get nervous and decide not to send me to Chicago.”

I solemnly swore.

“We French don’t need a visa for Canada,” he said. “And since I know the border between Canada and the United States is lax, I figured if I went to Canada first, I’d find a way across the border.”

“And how did you?”

“The second day after I arrived in Montreal, I was walking down the street when a young man came up to me and asked very timidly if I was by chance Jean Genet. When I admitted I was, he said he had read my work and seen two of my plays and could he do me the honor of showing me the city. Which he did for the next two days. I told him I was going to New York and didn’t have a visa. ‘That’s no problem,’ he said. ‘I’ll drive you across the border to Buffalo. You can take the train from there.’ If the border guards asked, he’d pass me off as his uncle. But at the border they just waved us through. And,” he said triumphantly, “here I am!” His delight at fooling the American customs was almost childlike.

“But, Jean,” I said, always the worrier, “that’s all right for New York. In Chicago, though, there’s going to be a lot of document checking. And the rumor is, Mayor Daley’s got the Chicago police force on full alert. What if you get arrested?”

H e shrugged, and I realized that for Genet the threat of arrest ranked far down in his grab bag of concerns. Still, it worried me, for I knew Jean had a long record, dating back to before the war, for theft, desertion, embezzlement, not to mention “public offense to decency.” But these petty imprisonments paled before the outrage his openly erotic, homosexual novels had caused in France, starting with Querelle de Brest and, later, with Our Lady of the Flowers and The Thief’s Journal. Years before, in Paris, Jean had also confided to Jeannette and me, at an evening with our close friends Monique Lange — who perhaps knew Jean better and longer than virtually anyone — and the Spanish novelist Juan Goytisolo, that in 1938 he had been a member of the Trotskyist Fourth International. However

short-lived and superficial his involvement, that gave him the added label of “Commie.” Given the incident at the American embassy in Paris, I had to believe that some worthy branch of government in Washington — probably the FBI — was privy to this information.* Once we had arrived in Chicago, Jean’s presence there was bound to be noticed immediately, if not sooner, by at least one member of the fifty- thousand-strong contingent of police, U.S. infantry, National Guardsmen, FBI, and Secret Service agents on hand to maintain disorder.

We went to lunch the next day, and at Jean’s insistence sat outdoors at a sidewalk cafe under a searing August sun. Inside, I knew, the place was mercifully air-conditioned, but Jean would not be swayed. “Inside, we see nothing,” he explained. “Here, we’re part of the city.” Despite the heat, Jean wore the same clothes throughout his stay: beige corduroy trousers, a light cotton shirt open at the neck, and a suede jacket of gracious origins but which had seen better days. Blacks sashayed past wearing tight- fitting pants.

Jean eyed them with open plea sure. “Les fesses americaines,” he muttered, shaking his head. “There’s something different, very different, about American buttocks.” He followed their undulations down the street until they disappeared around the corner. “New York,” he said, “reminds me of a colonial city. It is a colonial city!” Just then a garbage truck rolled by, stopping directly across the street to gather its loot. All three of the sanitation men were black, well muscled, and two of them were bare chested. Jean could not contain himself and *Actually, when finally released, the FBI file on Genet ran to more than five hundred pages. called over to the men in French, praising them for their rhythmic labors and gleaming chests.

“Jean,” I said, “I wouldn’t. I mean, they might not understand . . .” “Don’t worry,” he said with an irresistible grin. “They understand.” And indeed, all three waved back across the street at us and laughed broadly as the truck pulled away. I was beginning to believe that Jean’s innate charm and openness were like an invisible, protective wall around him, fending off all harm. That thought came back to me a few days later in the midst of the Chicago madness.

At Genet’s request, Esquire had hired Jeannette and me to squire him around New York and Chicago and to be his official translators. On Friday, the day before our ” flight to Chicago, Jean asked Jeannette to take him on a sightseeing tour of Forty-second Street. He’d heard a lot about the movies and peep shows of the area and wondered how they compared with the French equivalent. For an hour or two, Jean explored the lower “porno” depths of Manhattan with Jeannette in tow, emerging from each successive shop looking more and more gloomy. He shook his head. “These places are grim,” he told Jeannette. “There’s absolutely nothing erotic about any of them. Not that the French equivalent are much better, but at least the performers have some wit. Here everyone looks mechanical, depressed. These places are so dismal. Sex should not be dreary, it should be fun. I do not detect any trace of joy here. Let’s go back to the hotel.”

That afternoon we paid the obligatory courtesy call to Esquire at 488 Madison Avenue. Harold Hayes oozed Southern charm, asking Jean with a broad smile what he thought of America. Since I knew pretty well the answer, for Jean’s preconceived notions of this country were well- known — he found it racist, overbearing, a potential danger to the world by its military arrogance and might, coupled with a naiveté that allowed itself to get involved in stupid, winless wars, for example, Vietnam — I feared he might blow the deal on the spot, for candor was one of his many dangerous virtues. Jeannette and I were once again fooled by him, taken aback when he declined to respond, merely saying that as a guest of America he preferred not to abuse its hospitality, that he would doubtless have a fairer impression post-Chicago. One of the editors, whose name I had not caught, assured Genet that he was among friends and should feel free to speak openly. Didn’t the fact that the magazine had chosen him to cover the convention signal its openness to controversy? Jean, changing moods, said, “Oh, no, you chose me because of my name. Pure snobbery!” Which sent an immediate chill throughout the already- air-conditioned room.

The young, simpatico editor John Berendt was the Esquire staff member assigned to (e)squire us through the shoals of Chicago’s windswept waters. Affable, attractive, and efficient, he handed us our press credentials and plane tickets. He’d be ” going out a day ahead. With us on the “flight was my old friend Terry Southern. Bill Burroughs, coming from London, and the seasoned journalist John Sack, coming from God knows where, would join us later in the day.

On the plane to Chicago, we tried to brief Jean on the current state of American politics, reminding him of the difference between Republicans and Democrats (Genet: “There isn’t much, right?”), the discontent among the young, the dark horses among the Democrats who might have a chance of upsetting Hubert Humphrey. Genet cut us off.

“With young Kennedy dead, the only one with a chance is McCarthy, no?” he said. “And as I understand it, he doesn’t stand much of a chance. The party doesn’t like him. Is that true?

“And how did this fellow Nixon get nominated? He’s such a bad person. Does America like bad politicians? In France, all politicians are bad. But here I thought you had some good ones.”

Not many, we admitted, but Gene McCarthy stood head and shoulders above the rest.

“You seem to shoot all the good ones. Will McCarthy be in Chicago? He won’t win, but I’d like to see him.”

Yes, McCarthy was due in on Sunday, and we planned to see him.

“Anyway,” Jean said, “it doesn’t matter. I plan to write a piece as seen through the legs of a Chicago policeman.”

I wasn’t sure I understood.

“There are going to be a lot of policemen in Chicago, right? Maybe thousands? The policemen will be between us and the politicians. So if you want to write about the politicians, our viewpoint will be from behind the police. I’ll write the piece from behind a Chicago policeman. Maybe from between his legs.”

Hmmm, I thought. This could be truly interesting . . .

On Friday, Grove gave a lunch for Genet in Barney’s office above the Evergreen Theater on Eleventh Street. Most of the conversation focused on the events- to- be in Chicago. For days, the newspapers — and especially television — had been enumerating the various “outside” (read: unoffiial) disruptive forces that threatened to turn the host city into a Roman circus. A number of countercultural organizations had issued a clarion call to their

constituents to show up in Chicago to be both seen and heard: “flower children, peaceniks, hippies, yippies. Dave Dellinger, editor of Liberation, a leading figure in the movement to end the war in Vietnam, who the previous fall had led the highly successful and politically effective Pentagon march, would be coordinating similar marches in Chicago, it was reported. The SD@ — Students for a Democratic Society — were expected in force. The yippies, led by the stalwarts Jerry Rubin, Abbie Hoffman, and Ed Sanders, were said to be bringing, appropriately, a pig to Carl Sandburg’s “hog butcher for the world,” not for slaughter, but for nomination. In their eyes, nominating a 150- pound porker for president made fully as much sense as naming a Humphrey of roughly equal weight to the ticket. The country was still in shock over the assassination two months before of a second Kennedy: Bobby, however controversial and disliked by some, had gained immediate stature from martyrdom, and his shadow lay broadly over the next week’s events. After his primary victory in California, Bobby had become a viable alternative to Hubert Humphrey. Much of the protest in Chicago was aimed at the notion of a closed convention, that Humphrey the Handpicked was not only a shoo-in but, symbolically, the assurance that the Vietnam War would continue and probably escalate. Gene McCarthy would be there, but Bobby Kennedy had effectively hobbled his candidacy, and the senator had nowhere near the votes necessary to make it a contest.

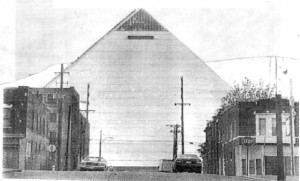

All the media hoopla predicting the breakdown of law and order prompted Mayor Richard Daley to reassure his fellow Democrats that their convention site would be made safe and secure. The twelve- thousand- strong Chicago police force, beefy and blue, was on full alert and prepared to handle any situation that might develop. Besides, as backup, there were always five thousand members of the National Guard, four thousand Illinois state troopers, six thousand American soldiers in battle uniform, not to mention swarms of FBI and Secret Service agents. All of which must have been most reassuring to the delegates.

Given the subtleties and idiosyncrasies of the American nominating process, plus the extraneous, contradictory elements of this year’s convention, I had assumed as I translated the gist of the conversation to Genet that most of it was over his head. Again, I had underestimated the good gentleman.

“The children are fed up with the old farts in power,” he concluded.

“Your Vietnam is our Algeria. To me, all this sounds like April in Paris.”

He was referring not to the romantic song but to the events four months earlier that had brought France to a virtual standstill and forced an entrenched government out of office. Genet, it turned out, knew a lot more about politics, especially their inner workings, than Esquire, or any of us, had ever suspected. Genet reiterated to everyone around what he had confided to me the day before — he planned to write his piece by viewing events through the inverted V of a Chicago cop’s thighs!

“But last night,” he said, “I watched your television, and it showed some of those flics [cops]. The thighs are still important, but I was also impressed by their bellies — they wear their belts and their revolvers beneath their bellies. And the visors: they all wear visors that cover and shield their faces. You cannot see their eyes, but they can see you. So I shall perhaps write each day not only from between the thighs but also from the viewpoint of the bellies, the visors, the revolver.”

Somehow, Genet knew that Barney was from Chicago and had asked him at our Friday lunch if he was going, too. Barney had responded that unlike Jean he didn’t have a special purpose that would justify his going.

“The purpose,” Genet said, “is to be there, no?”

Barney said that he had to go to the country — East Hampton — that afternoon but that he might well ” fly out Saturday or Sunday.

****************

Driving from O’Hare Airport next day, we were all struck by the desolate, empty outskirts. A vision of utter poverty, neglect, despair.

“Where are all the blacks?” Genet wanted to know. “If this is where they live, I can’t imagine some people aren’t out in the streets.”

Occasionally, at a street- corner grocery store, a few blacks were hanging out, but Jean was right: Where was everybody? Maybe, I figured, the massive presence of the police throughout the city was an inducement for them to stay inside. But Jean was unconvinced.

We checked into the Chicago Sheraton on North Michigan Avenue and agreed to meet at six o’clock in the Downstairs Lounge to make plans for the next five days. That evening we were scheduled to meet Dave Dellinger and hear what he had to say. Then, after dinner, off to Lincoln Park, where most of the protesters had gathered. By this time there were several thousand of them, and without a hotel room to be had in the city, most had come prepared to camp out in Lincoln Park throughout their stay. But that afternoon Mayor Daley’s office had thrown down the gauntlet by announcing that Lincoln Park would be closed at 11:00 p.m. Everyone would have to be out by the curfew or suffer the consequences.

Burroughs, who had flown in from London that afternoon, joined us in the bar, dressed, as always, more like a Midwestern banker than the true revolutionary he was. Tall, thin, and with a deadpan face that would have given Buster Keaton a good run for his money, Burroughs was the authentic black sheep of the famous family that gave its name to the adding machine and computer company. I had been his editor at Grove for several years now, and we had become good friends. I liked and admired him immensely and felt — as I feel today — that he was a major, if much misunderstood, writer, one of the great experimentalists of our time. Still, he remained to me an enigma: the exterior was impeccable in look, dress, and manners; the inner man was a nexus of high subversion. Not since Sade, in my view, had a writer used more effectively and tellingly an addiction, an obsession, as a creative springboard to inveigh against the clichéd world of the dull, the hypocritical, and the pretentious.

He and Genet had never met, but each knew — and admired — the other’s work. It was obvious they struck an immediate bond, and for the next two hours we exchanged ideas and formulated plans, some serious, some mad, all impractical, since we had no idea what awaited us in the streets. If Berendt was nervous about his charges’ disparate fantasies, he did not show it, even as drinks flowed and exchanges became less and less coherent.

Burroughs announced that Allen Ginsberg was in Chicago for the “events” and wanted very much to meet Genet. Allen had come, convinced that, using a method of chanting he had learned in India not long before, he could calm the troubled waters and help prevent violence.

A little before eight, Jeannette, Genet, and I drove over to Dave Dellinger’s Peace Headquarters. His “peace room” was a nearly empty, poorly lit place with glassless windows covered with torn plastic that flapped in the night wind.

“We’re not seeking a confrontation,” Dellinger said before anyone had even had a chance to ask a question. A gentle but imposing man with graying hair, he looked more like presidential timber than any of the candidates from either party, with the possible exception of Gene McCarthy. His staff seemed to consist mainly — or perhaps solely — of his son Ray, clad in khaki and wearing a blue beret, who hovered protectively over his father.

“We’re here simply to protest the foregone conclusion that there is no alternative to Humphrey. And of course to express our continued opposition to the war in Vietnam.

” Did he think there was going to be violence? asked Genet. Would the Chicago police attack young people – those Genet called the “gentle children — in the park? “I can only hope the mayor’s office would reconsider its position,” Dellinger replied. “Maybe Mayor Daley will realize that the best way to deal with a situation like this is to accommodate it, not defy it,” he said.

We were then invited to join Dellinger in the protest march scheduled for Wednesday. I translated the invitation for Genet, telling him that, however peaceful the intent, there could well be violence, probably arrests, and reminding him that he had no visa.

“Of course,” he said. “Of course we will march.”

Allen Ginsberg was staying at the Lincoln Park Hotel, just opposite the park itself, which was our next nonmilitary objective, so we decided to drive over, take the pulse of the park, and see if we could find Allen. I was elected by unanimous vote to do the driving, doubtless on the basis of my long experience in manning getaway cars. Allen was not in his room, we were told, but might be in the park. He had been seen leaving, carrying his instrument. When I translated this for Genet, he smiled malevolently and said, “I certainly hope so.”

“Hope so what?” I asked.

“That he’s taken his instrument with him,” he said.

“The man’s referring to a musical instrument,” I said.

“Ah!” said Jean. “I thought he meant the instrument.”

We arrived there about 10:00 p.m. to a menacing sight: hundreds of blue-clad policemen equipped with billy clubs, Mace, gas masks, and riot guns lined the sidewalk circling the park, which was pitch- dark except for a smattering of bonfires here and there. The police, as Genet had imagined them, were beefy and bellicose, the terms are not too strong, and standing among them, like some huge, quiescent, prehistoric animal left over from a grade- B movie, was an armored vehicle on top of which sat a bank of darkened searchlights. Near the vehicle stood a cop with a bullhorn: “This is the final warning. Clear the park. The park will be closed at eleven o’clock. Anyone remaining will be subject to arrest.”

In the distance, we spotted Ed Sanders, a writer and member of the rock group the Fugs, slinking along the edge of the park just beyond the grasp of the blue-clad finest.

Terry, always the wit, shouted out to him: “H ey, Ed! Where’s that loony fruit Al Ginsberg?”

Ed stopped in his tracks as though pierced, turned, and glowered in the direction of the offending voice, ready to do battle or flee, as reason dictated. Then he saw it was only our wacko group. “He’s doing his thing,” Ed told us, “over by that fire.”

His “thing” was chanting the word “om” over and over in the darkness, accompanying the chant with a portable harmonium (his instrument). The oms varied in tone, intensity, pitch; some were staccato brief, others drawn out for several seconds. Seated around him were a couple hundred people, most echoing his chant, others immersed in presumably peaceful thought. Nearby, a group of blacks was playing a flute and bongo drums. Not long before, we were told, as the bullhorn threats grew more strident, rumors had begun circulating that the police were moving in, and some people had panicked. Allen’s om-ing, however, had had a calming effect, and from a very small circle of thirty or forty, his disciples had grown impressively. As we approached, Allen saw that Saint Genet was among us. He broke off his chant, came over, and prostrated himself before the master. Jean, seemingly neither surprised nor embarrassed, merely smiled. In fact, I suspect that the completely surrealistic world into which he had landed had by now inured him to virtually any surprise. We sat down with the protesters — numbering by now more than a thousand, I would guess — and began chanting with the best of them. Genet seemed especially delighted by the nocturnal gathering and chimed in his om- ing in perfect pitch. It was by now past eleven, and although the bullhorn warnings continued unabated every few minutes, we had begun to take them for idle threats. Maybe Mayor Daley had finally been touched by grace.

But no.

Terry Southern described the next half hour’s events with his usual understated acumen:

Burroughs looked at his watch, and with that unerring awareness of which he is capable, muttered, “They’re coming.” At that instant, the banks of searchlights blazed up on the armored van which was already moving toward us. Fanned out on each side of the van were about a thousand police.

“Well, Bill, I think we’d better pursue another tactic,” I suggested, getting to my feet. What the hell, we were supposed to be here as observers, not as participants in any of Allen’s crackpot schemes. That the entire reportage team should be busted the first time out was unthinkable. Genet was the most difficult to persuade, but finally, on Ginsberg’s insistence, we all went up to his hotel room.

There, all inhibitions gone (if ever there had been any), Allen knelt in front of Jean and kissed his feet. “I have read Our Lady of the Flowers,” he said, still on bended knee, “one of the great works of the century. And you, monsieur, are a great saint.”

That night, on television, America saw its children being clubbed, beaten, kicked, maced, and gassed as the rampaging Chicago cops advanced, in a pincer action, on both sides of the armored van’s searchlights. It was, to Americans unused to civil violence, who believed that such confrontations between police and civilians were a foreign vice, a shocking sight. But as always television is a filter as much as a recorder; most of the time it creates a distance between viewer and event. Having lived that event — and the even more violent nights that followed — I can attest to the difference. One point, among many others, that television failed to capture that night was the fact that by employing a pincer movement, the Chicago police had no desire to clear the park. They wanted to club the kids. For as the crowd dispersed and headed for the park’s fringes, presumably leaving the cops behind, it found itself facing another equally menacing phalanx of blue at the park’s exit. Thanks to Terry’s perspicacity, and Allen’s kind hospitality, we were a few dozen steps ahead of the crowd and reached the edge of Lincoln Park before the pincer movement took its toll.

Again, Terry Southern:

Near the street, I glanced back in time to see [the cops] reach the place where we had been, and where a dozen or more were still sitting. They didn’t arrest them, at least not right away; they beat the hell out of them — with nightsticks, and in one case at least, the butt of a shotgun. They clubbed them until they got up and ran, or until they started crawling away (the ones who were able), and then they continued to hit them as long as they could. The ones who actually did get arrested seemed to have gotten caught up among the police, like a kind of human medicine ball, being shoved and knocked back and forth from one cop to the next, with what was obviously mounting fury. And this was a phenomenon somewhat unexpected, which we were to observe constantly throughout the days of violence — that rage seemed to engender rage; the bloodier and the more brutal the cops were, the more their fury increased.

NOTES FROM CHICAGO DIARY

Sunday, August 25. Morning.

About eight o’clock, awake but before we are out of bed, a knock on the door. It is Jean, asking to come in. I open. The mischievous gnome, whose room is a few doors down, is wearing a Japanese style kimono and bearing a sheaf of paper in his hand. Jeannette pulls the covers a bit higher as I stammer apologies for being a slugabed. Jean’s speech more than a bit slurred — not from drink, but from Nembutal, I had been told by Rosica,* which Jean takes to sleep. He wants to read us his first day’s reportage. I sweep him in with a grand, princely gesture. Jean heads not for the chair but straight for the bed and crawls in beside Jeannette, patting the sheet beside him, a clear invitation for me to join. Rub- a-dub- dub. In I go. Jean begins to read:

THE FIRST DAY: THE DAY OF THE THIGHS

The thighs are very beautiful beneath the blue cloth, thick and muscular. It all must be hard. This policeman is also a boxer, a wrestler. His legs are long, and perhaps, as you approach his member, you would find a furry nest of long, tight, curly hair . . . A few hours later, about midnight, I join Allen Ginsberg in a demonstration of hippies and students in Lincoln Park: their determination

to sleep in the park is their very gentle, as yet too gentle, but certainly poetic, response to the nauseating spectacle of the convention. Suddenly the police begin their charge, with the grimacing masks intended to terrify; and, in fact, everyone turns and runs. But I am well aware that these brutes have other methods, and far more terrifying masks, when they go hunting for blacks in the ghettos, as they have done for the past 150 years. It is a good, healthy, ultimately moral thing for these fair-haired, gentle hippies to be charged at by these louts decked out in this amazing snout that protects them from the effects of the gas they have emitted . . . The person who opens her door to receive us as we try to escape from these brutes in blue is a young and very beautiful black woman. Later, when the streets have finally grown calm again, she offers to let us slip out through the back door, which opens onto another street: without the police suspecting it, we have been conjured away and concealed by a trick house . . .

Sunday Afternoon

We drive out to Midway Airport to cover Gene McCarthy’s arrival. Jean is especially intrigued to see this “outsider,” the decent alternative to the rigged convention. Several thousand people have gathered — still, a numerical disappointment, I would think — but their colorful, flower- bedecked signs, WE WANT GENE, are waving rhythmically, as if a sea of windblown flowers. Three platforms — actually the empty beds of trucks — are gathered in semicircle. On one, a rock group; on another, a brass band. McCarthy’s plane is about half an hour late. Finally it arrives. Gene, smiling broadly, descends and scrambles up onto the empty platform. Jean remarks on how little police protection there is for him. Virtually none, in fact. McCarthy begins to speak, but no sound emerges from the mike. Dead. Gentle tapping fails to bring it to life. Jean murmurs: “Sabotage?” Realizing how often he is, with a single word or thought, prescient, I wonder if he isn’t right. McCarthy hops over onto the platform of the rock group — no power there either. Ditto the brass band. H e returns center stage, and there, miraculously, sound has been restored. He is tall, with a generous shock of gray hair, and a smile that ought to win millions of hearts and, more to the point, votes. I translate for Genet as he speaks. He is here not as a spoiler but as a winner. He will not be denied his final effort to turn the convention around. It has been a long and difficult eight months, but he has voiced an alternate opinion and been heard. The convention cannot ignore your — he is referring to the crowd — demands.

GENET ON GENE:

As McCarthy leaves the speaker’s platform, it seems that no one is protecting him, save for the sea of flowers painted by the hope-filled men and women . . . In order for McCarthy to arouse such enthusiasm, what concessions has he made? In what ways has his moral rectitude been weakened? And yet the fact remains that all his speeches, all his statements, reveal intelligence and generosity. Is it a trick? . . .

I realize that in his mind, as in his writing, Genet is relentlessly probing. He has seen and lived too much, and is too brilliant, to accept any surface for what it seems. Especially in politics. But also in most other life situations. His attitude is not to be confused with cynicism, an entirely different stance. No: instinctively, he likes McCarthy; but, automatically, he is searching for the flaw, faint or fatal, the secret motivation, the person behind the mask. Seduced by the man, and hoping to learn more about this “outsider,” Genet asked if we could interview McCarthy, whose headquarters we had learned were at the Conrad Hilton Hotel. When we arrived at the fifteenth floor, the senator was not there — otherwise engaged, we were told — but would be available later. He would be informed of our visit. Again, Jean, impressed by the youth of McCarthy’s faithful, tugged my sleeve and said, “I thought all presidential candidates had police protection. Not one in sight, no?” And indeed there was none.

Monday, August 26. Morning.

Eight o’clock. Knock on door. This time we are prepared. Again, kimono- clad Jean crawls into bed, unfolds his blue- lined sheets of paper, and begins to read.

THE SECOND DAY: THE DAY OF THE VISOR

The truth of the matter is that we are bathed in Mallarmean blue. This second day imposes the azure helmets of the Chicago police. A policeman’s black leather visor intrudes between me and the world . . . Supporting this visor is the blue cap — Chicago wants us to think that the whole police force, and this policeman standing in front of me, have descended from heaven — made of a top-grade sky-blue cloth. But who is this blue cop in front of me? I look into his eyes and I can see nothing else there except the blue of the cap. What does his gaze say? Nothing. The Chicago police are, and are not. I shall not pass . . .

I listen intently as Jean reads. The Chicago police as Mallarmean blue? I wonder how Esquire will cotton to that wool. I have to assume, though, that if a magazine makes the mistake of inviting genius to grace its pages, it cannot be too upset or shocked by the results. And I marvel that Jean will, as he had warned, write his piece from the viewpoints of the policeman’s various body- and uniform

parts. While he had never set foot in Chicago, never seen a Chicago policeman in the flesh, I suspected that he knew before coming exactly how — and probably what — he would write.

Music, we learned, was one of Genet’s abiding passions. His knowledge of music is encyclopedic and profound, his insights original. In the middle of the po liti cal maelstrom Jean and Jeannette abandon themselves to the subject they both love. I listen with a mixture of awe and humility. Where, I wonder, did Genet acquire his musical expertise? Jeannette tells him of her plan for a recital to give back in New York that fall. Although she had been trained as a classical violinist, jazz had always been part of her musical landscape. For the past several months she and several talented jazz musicians had been ” jamming” together. The drummer was Jack DeJohnette, the pianists Keith Jarrett and Chick Corea, with three other jazz musicians. When Jeannette mentioned to Genet her plan — innovative at the time — to divide her forthcoming concert between classical and jazz repertory with the appropriate change of costume, Jean got very excited and appointed himself on the spot

her production and stage manager. We knew of Jean’s involvement in the theater, but his musical erudition was a revelation to us both.

Late morning, we all head for Lincoln Park. The yippies are out in force, unfazed by last night’s clubbing and gassing. In fact, the events — probably due to television coverage — have galvanized other forces to join them, including the clergy, who promise to be out in force next time. The yippies proudly display their candidate, the Pink Pig, which they keep in a burlap bag. Burroughs, believing in fairness and equal time, rec ords the pig’s snorts and squeals, which he’ll doubtless later splice in some kind of cut- up masterpiece into the cops’ threats, the delegates’ speeches, the blaring music.

Monday Afternoon

Jean, Burroughs, Terry, Allen, Berendt, Jeannette, and I — plus a new member of our sexy septet, the Beatles’ photographer Michael Cooper — head out in two cars for the Convention Hall. Trouble parking, as interdictions abound, and the good citizens of the area, suffering from a severe case of hippie phobia, scream at us, “Don’t you park in front of my house! I’ll call the police!” Can’t totally say I blame them from the looks of us, not to mention the hippie mayhem they witnessed on television last night that was coming mighty close to their hallowed homes, by God! As for ap-pearances: Genet as described. Allen bushy. Terry scruffy, despite his protestations to the contrary. Yours truly not exactly a fashion plate either. And to top off the sartorial nightmare, Michael Cooper was decked out in a basically purple outfit — including the hat — with one pant leg blue with white stripes, the other red with polka dots. Shoeless to boot. Only Jeannette, Burroughs, and Berendt lend a modicum of decorum. Not enough, I fear, to offset the others in the eyes of the police swarming around the Convention Hall. In circling to land our outer- space vehicles (“Why,” Genet wonders out loud at one point in our travels, noting the model name of our rented Ford, “would anyone name a car ‘Galaxie’?”), we see the convention area looks more like a military installation, an armed camp, than the center of the demo cratic pro cess. Three rings of barbed wire, the outermost a good quarter mile from the entrance, and at each barrier a checkpoint manned by a phalanx of Chicago’s finest. Jean has altered my optic, I can no longer refrain from checking out the cops’ bellies and thighs. Precisely as described, to a man. Meanwhile, “concentration camp,” Jean keeps muttering, appalled by the quasi-military surroundings. Trepidations for my charge. There is no way Genet is going to get through all three checkpoints unscathed. I picture him handcuffed and shackled. “Officer, you don’t understand. This is one of the great writers of our time. His ID is back at the hotel. You can’t arrest him.” Burroughs, on the contrary, pleased as punch, reveling in the moment. H is normally deadpan face creased with a visible — yes, Visible — grin. Armed with his ubiquitous tape recorder, Bill keeps it running full tilt at each checkpoint, as the cops question us at length about our race, religion, professional purpose, and planet of origin. Burroughs, staunch proponent of the cut- up method of writing, doubtless gathering material for future work as well as recording the historic moment. A double whammy, or How to Turn Impending Disaster into Creative Delight.

Miraculously, after proving all our press credentials are in order, we get through the first two checkpoints. But at checkpoint three, we realize the outer Boys in Blue were simply passing the buck. The real test was upon us. At the inner circle, an unusually bulky lieutenant stops us cold. Berendt the Normal draws himself up full height. “These are bona fide Esquire-accredited journalists, ” he says firmly. Slight quaver. Wait here. The lieutenant disappears and returns shortly with a gray-flannel human, indelibly stamped National Security, Secret Service Division. Carefully checks all of our press credentials. Then ID s, one by one. I hold my breath. This is it: Genet’s outlaw status will inevitably be revealed. No visa, no washy. Juzgado, Jean baby. But when Secret Ser vice comes to G enet, instead of asking for his ID , gray ” annel pauses, looks, smiles, then thrusts out his hand and vigorously shakes Jean’s. H as he by chance recognized him? I doubt it. Still, there is no other explanation. As for Jean, he looks disappointed. In any event, his magic has worked once again. Secret Service to lieutenant: “They’re okay. Let them through.” Disbelief from the Blue, but only a slight shake of the head as if to say, “Your responsibility, hotshot.”

Inside we mount to the rafters. Speakers droning. Flags waving. Music blaring. Party-hatted delegates swaying. Burroughs madly recording. Jean more upset by the minute. We endure for an hour, maybe an hour and a half. Terry: “The fix is in. Let’s get outta here.” Unanimous agreement. Our return to the hotel quietly depressed, as if some new low point of the trip has just been witnessed. What has been happening in the streets was of no consequence to the people inside the Convention H all. This could be Any Convention,

Any Year.

Tuesday, August 27. Morning.

Knock, knock.

“Who’s there?”

“Jean.”

“Jean who?”

“Jean Genet.”

“Ne vous genez pas. Come right in!”

Our now- routine morning journal. Jean’s voice thicker this Morning — one sleeping pill too many? — but his prose just as lucid as ever.

THE THIRD DAY: THE DAY OF THE BELLY

A policeman’s beautiful belly has to be seen in profile: the one barring my route is a medium- sized belly (de Gaulle could qualify as a cop in Chicago). It is medium- sized, but it is well on its way to perfection. Its owner wheedles it, fondles it with both his beautiful but heavy hands. Where did they all come from? Suddenly we are surrounded by a sea of policemen’s bellies barring our entrance into the Democratic convention. When I am finally allowed in, I will understand more clearly the harmony which exists between those bellies and the bosoms of the lady- patriots at the convention — there is harmony but also rivalry: the arms of the ladies of the gentlemen who rule America have the girth of the policemen’s thighs . . .

I wonder if Jean will give, in his early wake- up report, his reaction to yesterday’s near slammer miss at the convention. He promptly does:

The chief of police — wearing civilian clothes and his belly — arrives. He checks out our passes, our identification, but, obviously a man of taste and discretion, does not ask to see mine. He offers me his hand. I shake it. You bastard . . .

Genet takes his Miraculous Protection totally for granted.

*A bad pun, but one that delighted Genet. Because of his daily matinal door knocks, we said he reminded us of a (bad) American joke series, namely, the antique “knock, knock” jokes. The pun here is on Genet’s name and the similar- sounding French verb, gener, literally to embarrass or inconvenience. Thus, “Ne vous genez pas,” which freely translates as “Be my guest” or, in this instance, “Come right in.”

Tuesday Afternoon

Back to the convention. Security no problem, our previous day’s entrance assuring us reentry with no questions asked. The Esquire appointed freelance photographer, Jack Wright, having been summoned east on another (more important?) assignment, Berendt asked if any of us stalwarts had photographic knowledge or experience. Silence all around. Stupidly, I admitted to having, in my Paris days, accepted two magazine assignments to North Africa, which included taking the pictures. The job, alas, was mine. He handed me the Leica, which Wright had magnanimously left behind. For the next three days, I took eight rolls of film, focusing on our hardy group in perilous situations (at the Amphitheatre, on the streets, at the Coliseum, in Grant and Lincoln parks). Superb all, I am sure, except for a slight mishap, to be acknowledged later. The convention still a preordained bore, we stayed but an hour. Then off to Lyndon Johnson’s Unbirthday Party at the Chicago Coliseum, organized by Jerry Rubin and the yippies. “Ah,” breathed Jean, “how much better the air is here.” Perhaps a political contrast, but more likely referring to the stench around the convention center, which was hard by the storied Chicago stockyards. Later, Jean would describe the occasion at the Coliseum: “Part of America has detached itself from the American fatherland and remains suspended between earth and sky.”

Tuesday Night

Back to Lincoln Park about eleven. Different feeling in the air. About twice as many people as on Sunday, we estimate, and two or three times as many bonfires in the night. Priests and ministers, true to their word. A large wooden cross has been constructed in the middle of the park. A fair number of men wearing hard hats and helmets; several dozen medics in white, with Red Cross armbands. Allen is worried: no amount of chanting will prevent violence to night. Palpable tension in the air, not here on Sunday. And to night, a great many more cops out. Is it my imagination, or do they all seem bigger? Taller? Stouter? Another difference tonight, journalists everywhere. Recognizable media figures milling about. I note, among others, the impressive silhouette of Clive Barnes of The New York Times seated on the grass not far away. Sent to cover the Living Theater no doubt. No: the theater of the absurd. Will they — the media — deter violence? Bashing kids is one thing; bashing journalists quite another. Still, the word is that Mayor Daley has not changed his tune. On the contrary. Again the repeated bullhorn warnings, for well over an hour. Shortly after midnight, cops begin moving in, shoulder to shoulder, riot guns at the ready, gas masks donned, preceded by a car filled with four cops wielding shotguns. Someone tosses a stone, or a brick, at the lead car, breaking the windshield. All hell breaks loose. Tear gas, ten times worse than before. The cops charged, both to relieve their colleagues in the car, who were surrounded by furious protesters twenty or thirty strong, now rocking the vehicle back and forth in a clear attempt to overturn it, and to track down and club the unwelcome intruders.

The first night Terry had suggested a tactical retreat on the premise that it would be unconscionable for such a prestigious reporting team to be wiped out so early in the game. To night, when we saw the brick- through-windshield, he again uses good common tactical sense by suggesting that valor will best be served by rapid strategic withdrawal. We flog our way through tear gas, coughing and stumbling, but finally reach the presumed safety of the street beyond the park. Hundreds of demonstrators pound toward us, heading the other way. “Run!” a girl shouts as she passes. “They’re

coming from that direction!” and she points away from the park in the direction where we thought safety lay. And indeed, lumbering toward us was another wall of blue.

“Shit,” Terry hisses.

“Hmmm,” Burroughs observes.

“Q u’est- ce qu’il y a?” Jean wonders. What’s happening?

We start back up the street, but realize that’s No Exit.

“In here,” I yell, and we all pile into the hallway of a house, move as far to the back as we can, and crouch down.

Jeannette, who as a little girl had lived through the German occupation of Paris, daily bombings, and more than once seen German soldiers running through the streets in pursuit of their prey, has a seizure of dejë vu. Trembling, uncontrollable trembling. I put my arm around her, but the trembling only increases.

Through the glass hallway door we see the cops thundering past and for a moment think we are safe. But then we hear them next door and realize they’re routing out the recalcitrants and beating them unmercifully as well. Moments later, in rush four cops, clubs raised. Jean was closest to the street door, therefore first in line to be clubbed. As the cop raised his billy to hit him, Jean

simply looked at the man — I dare say straight in the eye — and for several seconds the club remained poised above his head. Then, slowly, he lowered it, as if his arm had been tugged downward by some invisible, omnipotent, doubtless Genet-inspired force.*

*John Berendt remembers the moment quite differently and, alas, far less romantically. He recalls pressing Genet against the wall and shouting to the cop, “Stop! He’s an old man! Don’t!” And he didn’t.

“All right, you Communist bastards,” another cop said, “get the hell out of here.” And with that they prodded us out into the street, back into the Coliseum, where we felt like early Christians — understanding for the first time why the man we were escorting had been called Saint Genet. Through a labyrinth of side streets, we make our way — not proudly — back to the hotel.

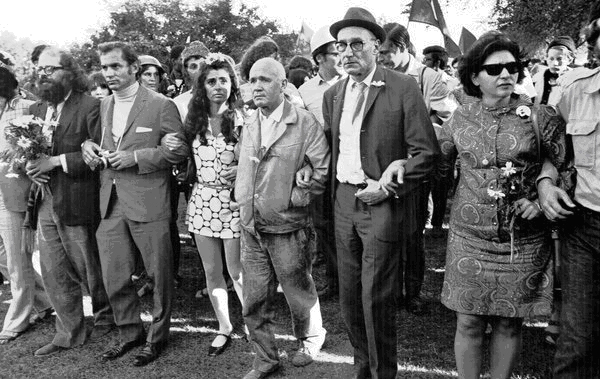

Wednesday, August 28

Dave Dellinger’s Peace March had evolved into a demonstration in Grant Park, for Mayor Daley has not only refused to grant a permit but brought in the National Guard to buttress the beleaguered police. It is the Guard that blocks our path, standing across the proposed line of march. Unlike the mayor’s Bellies in Blue, these young men, half the age of the police and in most instances half the girth, look slightly uncomfortable, as if they would prefer to be elsewhere on this sweltering August afternoon. Our heavily literary, notably unmuscular group has been invited to be in the front, among the leaders of the march. We link arms and move slowly forward, noting with unease the bayonets gleaming in the bright sunlight before and beside us. We shuffle, mark time, stand still. Finally, after a long wait, we repair to Grant Park, where a stage has been set up. Singers strum guitars and sing of peace and brotherhood. Brightly colored balloons ascend into the cloudless sky. Speeches fill the afternoon air, distorted by less than perfect sound equipment. But we know the message. Shrill attacks on the unnecessary violence. Ringing denunciations of Mayor Daley. Equally scathing assaults on the official convention and the Democratic Party, purportedly the party of the people but obviously blind to the hue and cry of the country’s youth. Humphrey derided. The shamefulness and stigma of Vietnam.

Vendors sell hot dogs and hamburgers, Coke and Pepsi. If you close your eyes, the odiferous afternoon makes you think you’re at a July Fourth picnic, or out at the ball game, rather than taking part in high political drama. One group decides to set out on a symbolic march to the Chicago slaughter house. As we had earlier, they lock arms, eight abreast, and begin their peaceful walk, this time the front line made up of a group of blacks. Like us, they are blocked, this time by the Blue. Unlike us, they continue walking, straight toward the blue line, which stands fast. Then, again, the tear gas

and the blue line advances, clubs ” ailing. This is no Fourth of July. No ball game. It is late August in Chicago, 1968.

Thursday, August 29

One presidential candidate not invited to the convention was the comedian Dick G regory, who in Chicago is dead serious. Angered and frustrated at the city’s refusal to grant permits to marchers, Gregory has a brilliant idea. “Come on down to my house. No one can stop me from inviting you to a party.” Genet was delighted at the ruse. A man of great wit and humor himself, he responded immediately to the same quality in others. Here is Jean on that last day’s invitation to the ghetto:

Dick Gregory is inviting his friends — there are four or five thousand of them in Grant Park — to come home with him. They won’t let us march to the Amphitheatre, he declares, but there’s no law that says you can’t come on down to my house for a party. But first, he says, the four or five policemen who have stupidly allowed themselves to be hemmed in by the crowd of demonstrators must be freed . . . Gregory explains how the demonstrators are to walk, not more than three or four abreast, keeping on the sidewalk and obeying the traffic lights. The march may be long and difficult, he says, for he lives in the black ghetto of South Chicago. He invites the two or three who had earlier been beaten by the cops to head the march, for he figures the police, whose job it is to stop the march, may be less brutal with them.

We walk along the hedge of armed soldiers.

At long last, America is moving.

Anyone who doubts the prescience of Jean Genet should read the

opening of his last day’s report:

Is it necessary to write that everything is over? With Humphrey nominated, will Nixon be master of the world?

We flew back to New York Thursday afternoon. At the airport, an Esquire limousine was waiting to take us to a site in the Bronx where the cover-story photo was to be shot. No one had the foggiest notion what the cover shot was supposed to be, except that Esquire’s Chicago Four would be in it. We arrived at a desolate, deserted street, paved in brick, where a photographer awaited, together with a young male model who looked as if he had been dragged through the streets of Laredo by a posse of Western bad guys before being deposited in the Bronx. The photographer was perched a story above the street. The model was lain with his face down on the curb, his torso on the street, his legs on the sidewalk, his body and the surrounding pavement appropriately drenched in ketchup, which the photographer’s lens would pick up as blood. Genet, Burroughs, Southern, and John Sack surrounded the pseudo- hippie — was he dead or merely sorely wounded, this victim of Chicago’s mindless violence? — staring upward, with looks of accusation, at the offender, presumably Mayor Daley. Or Hubert Humphrey.

After the photo session, the car drove us back to Manhattan. Genet was beside himself.

“I detest sham,” he said, shaking his head. “Chicago was one thing. At least there you were a real participant. But this . . .” I conveyed Genet’s thought to Berendt, who, as always, was understanding,a calming influence. He asked that I try to explain to Jean that there was no way in the madness of Chicago that they could have taken a picture that would properly convey the scene as, he hoped, this simulated version would. Jean, not satisfied, simply shook his head.

The word “picture” gave me a start. For in the rush and tumble of Chicago, somewhere Jack Wright’s camera and my eight rolls of â lm had gone missing. Would everyone please check his bags and see if by chance they had its precious — nay, irreplaceable — material . . . Nothing. I knew Jack Wright was far from well-heeled and vowed to have Esquire reimburse him.

And Now for My Fee

Jean had agreed to write two pieces for Esquire, one of which, “The Members of the Assembly,” he had finished before he left Chicago. The other, entitled “A Salute to a Hundred Thousand Stars,” was in rough draft, and Genet said he would finish it that afternoon, since he wanted to leave New York on Saturday. I had already translated the first piece before leaving Chicago, since Esquire was on a tight deadline, and promised Harold Hayes that I would translate the second piece over the weekend if Jean gave it to me by the end of the day on Friday. Financial agreements on Jean’s Chicago trek had been made between Esquire and Jean’s agent, Rosica Colin. Jean was to be paid in dollars, in cash. I turned in the first piece that same afternoon, later calling Hayes to say Genet was leaving town the next morning and would like to be paid.

“He’ll be paid when both pieces are turned in,” Hayes said.

“You already have one to hand,” I said.

“And the other?”

“For Chrissake, Harold, we just got back, from five rather harrowing days, I might add.” I felt like asking Hayes how he had spent the past week — nothing dangerous, I trusted — but refrained. “Jean’s finishing up the second piece as we speak, and I promised Berendt you’d have the translation Monday morning. I’d say that’s pretty fast.”

“I repeat: he’ll be paid in full when we have his pieces in full. Since we have one, he can pick up half his fee this afternoon.”

I was furious. And ashamed, for it was we at Grove who had encouraged both Genet and Burroughs to accept the job. But I was dealing with a brick wall. Or someone with a brick for a brain. Or someone whose epithet rhymed with brick. I made one final, humiliating plea.

“Harold, I’m not sure you heard me. Jean is leaving tomorrow for Europe” — I refrained from saying he’d be leaving, precariously, via Canada, assuming he made it across the border without getting arrested — “and the agreement was he’s to be paid in cash, I believe.”

“If Genet wants the first half of his fee, he can pick it up this afternoon at the office.” Click.

For a moment, I became a Chicago cop, blind empathy, with a murderous urge to use my club. But I figured there was no use sparing Genet the solemn truth. The vision of genius laboring away in his hotel room on a piece for which he probably would not be paid struck me as the depths of the absurd. I grabbed a cab to the Delmonico and shot up to room 911. There he was, seated at a tiny desk, his neat blue-penned script covering a schoolboy’s lined white sheets.

“I’ve just finished,” he said, clearly pleased with what he’d written. “Shall I read it to you?”

“Please do . . . But first I should tell you . . . I just got off the phone with H arold H ayes . . .”

“I never liked that man,” he said. “When I first laid eyes on him in Paris, I didn’t like him. Did you tell him I needed my fee today?”

“Yes, we can go pick it up right now. The only thing is” — I saw Genet lock his blue eyes on my embarrassment as if he knew in advance what I was going to say — “they’re only going to pay you half your fee now.”

“Did you tell them I’m leaving tomorrow?”

“Yes, of course. H e wouldn’t budge. They say they only have one of the two pieces.”

“Here’s the other one,” Genet said. “I’ll give it to him when we go there.”

At the Esquire offices there was an envelope for Jean. H e opened it and counted the money. Nineteen hundred dollars.

“That’s only half,” he said to the receptionist in French. She smiled at the cute man, but the cute man wasn’t smiling back.

“I want to see Hayes,” he said. I passed on the message.

“I’m sorry, Mr. H ayes has gone for the day.”

I passed on the message.

Genet, without missing a beat, reached out and picked up the envelope containing “A Salute to a Hundred Thousand Stars” and stuffed it in his pocket. “Tell Mr. H ayes when I get my full fee he can have the second piece,” he said. I passed on the message.

Back in his hotel room, Jean took the pages and slowly, methodically ripped them lengthwise into a dozen pieces, tossing strips into the wastebasket.

I watched, increasingly ill as I saw the shattered manuscript disappear.

“Why the hell did you do that?” I said querulously.

“They’ll never pay me,” Jean said. He paused. “D id you ever notice,” he said, “that when there’s a difference between people who have money and those who don’t, it’s always the former who win? I’ve never known it to fail.”

Friday Night, August 30

Jeannette was preparing a farewell dinner at our house for Jean, Barney, and some other Groveniks. I was not looking forward to it now, since Jean’s foul mood was sure to permeate the celebration. But again I was wrong. If he was disturbed or angry — and I knew he was — he never let on, and the evening was a resounding success. In fact, I had never seen Jean in finer form, regaling us with stories of the past week.

What was the high point of Chicago?

“My meeting with the Black Panthers,” he said, almost in a rush.

“On Tuesday — no Wednesday — we went to a Free Huey rally in Grant Park where I met Bobby Seale, David Hilliard, and a third Black Panther leader whose name I didn’t catch . . .”

“Wendell Hillard,” I supplied.

“Right. Anyway, Seale gave this impassioned speech in which, if I understood Dick’s translation, he suggested the White House be painted black. What a splendid idea!”

Laughs all around.

“But I shook all three hands and told them I was with them in their struggle . . . And if one day they needed me, I’d come back.”*

*True to his word, Jean did come back a year and a half later, in March 1970, and involved himself deeply in the Black Panther movement.

The rest of the evening focused on the future, the upcoming Humphrey-Nixon race, about which Genet opined that it really didn’t matter who won. “They were both connards [assholes], were they not?”

At one point, he turned to Barney and said, rather gently, I thought, “You missed a great event in your hometown. I thought you were coming on Saturday,” his blue eyes boring into Barney’s.

“I know, I know,” Barney said. “Actually, at one point Saturday morning I got in my car in East Hampton and headed for the airport. But after a few miles I turned back. I don’t know why.” It was one of the few times in my long acquaintance with Barney that I saw him truly contrite.

“A shame,” Genet said. Barney, for whom “contrite” was a foreign word, lowered his head. “You missed a great event.”

Which ended the evening.

Before exiting Jean’s hotel that afternoon, I had been determined not to leave the despoiled manuscript behind. On the pretext that I had left something in the room, I went back up and rescued the remnants. The following evening, Jeannette and I drove Jean to LaG uardia, where, without further incident, he boarded a plane for Montreal. He had been in America less than two weeks, but as we headed home from the airport, we both had the feeling we had just lived a mini-lifetime.

“Why ‘mini’?” Jeannette laughed. “It seemed pretty ‘maxi’ to me.”

That Sunday, I managed to stitch the scraps together with Scotch tape, translated them, and sent the piece off to Harold Hayes with a note. Not surprisingly, I never got a reply.*

For several weeks I pursued Jean’s lost cause and also tried to get Hayes to reimburse Jack Wright for his missing camera. Jack was a friend of Terry Southern, who sent a barbed wire or two on Wright’s behalf as well. Finally, with Hayes’s continuing silence ringing in my ears, I wrote to the publisher, Arnold Gingrich, on December í7, in a post- Christmas Dickensian mood of ill humor. On D ecember 30, G ingrich wrote back:

In H arold’s absence . . . I can only give my impression of why you may have failed to hear from him.

*Later Genet’s agent, Rosica Colin, told me, however, that she had received, on Jean’s behalf, a portion of the fee agreed upon for the second piece, together with a standard rejection letter.

I got the feeling that Harold was up to here ($) on everything to do with Genet, after paying the horrendous bills that his presence incurred. This involved, as you know, not only expenses for Genet and you and your wife, but also a substantial payment for an additional piece, which turned out to be such a calculated piece of effrontery that Harold could only assume it had been written as a deliberate put- down.

Harold paid and paid and paid until he reached a point at which — I take the liberty of guessing — he would have turned down Jesus Christ himself if he had asked him to lend a hand at carrying that heavy cross up the Golgotha Hill.

If my impression is wrong, I am sure Harold will correct it upon his return.

Yours always sincerely,

Arnold Gingrich

Publisher

On January 15, with still no word from H ayes, who, it could be presumed, had returned from his “absence,” presumably self-imposed, I wrote Gingrich back. I first reminded him that Genet, a spartan soul, incurred costs in New York, before and after the convention, of a grand total of three hundred dollars. If that was excessive, he and I should sit down and redefine the term. As for the fee, that had been agreed between Hayes and Rosica Colin, so no surprises there, as none for our translation fee, which had been proposed by Hayes. My strong suspicion was that the magazine’s anger was directed not at Genet’s expenditures — which at any calculation had to be termed modest — but at his politics. I closed:

I am certain that Genet never made any bones about his feelings on the Vietnam War before he came here, and while Esquire has every right not to like the piece he wrote, it was most certainly not a calculated piece of effrontery, and I know that Genet takes the piece quite seriously. I gather, in fact, that it is being published in two or three major European

publications.

What I am saying in effect is that, if Harold “paid and paid and paid,” to the best of my knowledge he did not pay for anything, or at any rate, that he had not contracted for.

The night of our farewell dinner for Jean, I had taken Barney aside and told him the story of Esquire’s reneging. H e was as appalled as I, upset for Jean, and impressed by his good front throughout the evening. He also had an immediate and generous solution. If Esquire turned the piece down, we’d publish it in Evergreen Review and pay Jean the Esquire rate — which was five or six times ours. In due course, the piece appeared in Evergreen Review, which pleased Jean no end when I sent him the issue.

Strangely, he never asked how “A Salute to a Hundred Thousand Stars” had made it from the wastebasket of his hotel room to the pages of Evergreen Review.

| “Genet Comes to America, ” “The 1968 Convention, ” and “And Now for My Fee” from THE TENDER HOUR OF TWILIGHT by Richard Seaver. Copyright © 2012 by Jeannette Seaver. Used by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. All Rights Reserved. |

Visit: www.fsgbooks.com

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=522klJIDeaQ

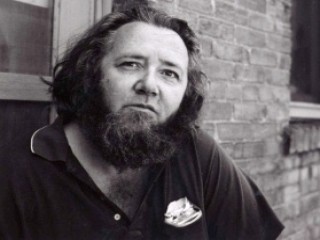

| ‘The Tender Hour of Twilight’ is a romantic literary memoir of Paris in the 1950s and New York in the ‘60s, by the renowned Translator (The Story Of O), -Editor-Publisher Richard Seaver. While a young Fulbright scholar, writing his thesis on James Joyce at the Sorbonne, Seaver not only found his lifelong true love Jeannnette Medina, but discovered and wrote a literary essay on the then unknown Samuel Beckett for the legendary literary journal Merlin. Grove Press publisher Barney Rosset read the essay, and 1959 hired Seaver as an Editor there. After 12-years of the twosome shepherding in the last golden age of writing and legally breaking down the age of puritanical censorship in America, Seaver resigned as Editor-in-Chief, for his own imprint at Viking Press in 1971.http://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/07/arts/07seaver.html?_r=2&ref=obituariesto finding his lifelong true love in Paris |

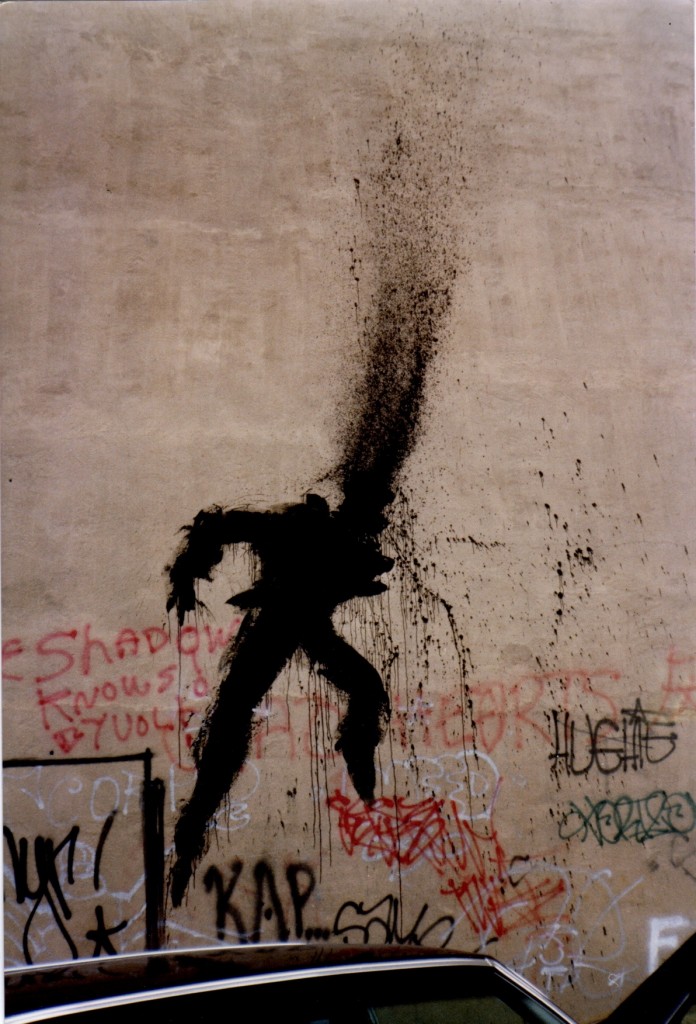

Photograph: Michael Cooper.

Photograph: Michael Cooper.